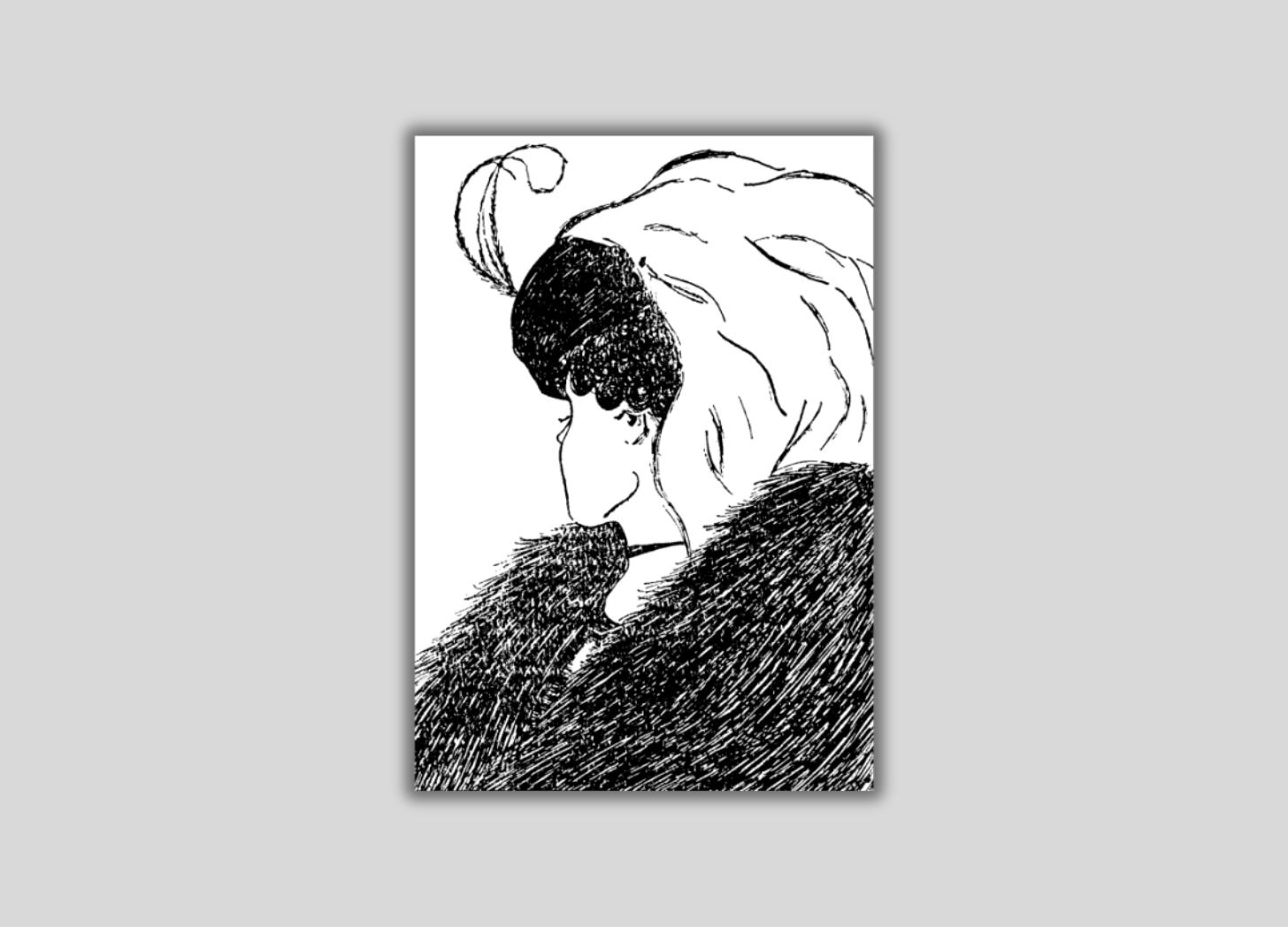

You've seen it. Honestly, you've probably seen it a hundred times since elementary school. One second it’s a stylish young woman looking away into the distance, showing off a delicate jawline and a tiny ear. Then—blink—and she’s gone. In her place sits an older woman with a prominent nose, a heavy chin, and eyes cast downward in a sort of weary contemplation.

It’s the old woman and young woman picture, officially known as "My Wife and My Mother-in-Law."

But here is the thing: it isn't just a parlor trick or a dusty relic from a 19th-century postcard. It is one of the most studied psychological tools in history. It tells us more about how our brains process faces, age, and social bias than almost any other image in existence. It’s a battle between your primary visual cortex and your social brain. Usually, your social brain wins before you even realize you’re looking at lines on a page.

The Secret History of the World’s Most Famous Drawing

Most people think a cartoonist named William Ely Hill invented this. He published it in Puck magazine back in 1915 with the caption "My Wife and My Mother-in-Law. They are both in this picture — Find them."

He didn't invent it. Not even close.

The image actually dates back to an 1888 German postcard. It was an anonymous creation, likely used for advertising or just as a "hidden image" novelty that was popular at the time. Hill just happened to be the one who gave it the catchy title that stuck for over a century. It's kind of wild to think that a nameless artist in the late 1800s created something that would eventually be used in 21st-century neuroscientific studies at Flinders University.

What makes it work is something called perceptual bistability.

This is basically a fancy way of saying your brain can't see both women at the exact same time. It’s physically impossible for your neurons to process the "nose" of the old woman and the "jawline" of the young woman simultaneously because they occupy the same visual space. Your brain has to pick a side. It flips a switch. One becomes the "figure" and the other becomes the "ground" or the background.

💡 You might also like: Dutch Bros Menu Food: What Most People Get Wrong About the Snacks

Why Do You See One First?

Ever wondered why some people immediately see the young woman while others are hit with the image of the older lady? It’s not just random luck.

A famous 2018 study titled "Perception of an ambiguous figure is affected by own-age social bias" really shook up what we thought we knew about this image. Researchers Ray Nicholls and Michael Nicholls showed the old woman and young woman picture to 393 participants ranging in age from 18 to 68.

The results were incredibly consistent.

Younger people almost always saw the young woman first. Older participants were significantly more likely to see the older woman. It suggests that our brains are "tuned" to recognize people who look like us or belong to our own social peer group. We are subconsciously scanning for "self-resemblance."

Think about that. Your brain is so biased toward your own age group that it literally filters out an entire person standing right in front of you.

The Anatomy of the Illusion

If you are struggling to see both, let’s break it down. It’s basically a map of shared features.

The young woman is turned away. Her "ear" is the old woman's "eye." Her "necklace" is the old woman's "mouth." Her "jawline" is the old woman's "nose."

📖 Related: Draft House Las Vegas: Why Locals Still Flock to This Old School Sports Bar

It’s genius design.

There is also a version created by psychologist Edwin Boring in 1930, which is why you’ll sometimes hear this referred to as the "Boring Figure." He used it to demonstrate how sensory data stays the same while our interpretation changes. The light hitting your retina doesn't change when the image flips. Only your mind changes.

The Science of Face Processing

The old woman and young woman picture is a heavy hitter in the world of "top-down processing."

Most of the time, we use "bottom-up" processing. We see a shape, we see a color, we put them together, and we realize, "Oh, that’s a chair." But with this illusion, your brain uses "top-down" logic. It uses your past experiences, your age, and your expectations to tell your eyes what they are seeing.

- Social Grouping: We categorize people instantly.

- Feature Integration: Our brains hate ambiguity. We want to "resolve" the image as fast as possible.

- Neural Fatigue: If you stare at the young woman long enough, the neurons responsible for that perception get "tired," making it easier for the image to flip to the older woman.

Interestingly, people with certain types of neurodivergence or those who process "local" details rather than "global" shapes sometimes find it easier to switch between the two. They see the lines for what they are—ink on paper—rather than a cohesive face.

Cultural Impact and Modern Usage

Beyond psychology labs, this image has permeated pop culture. It’s been on album covers, used in corporate "perspective" training, and has even been used in clinical settings to test for certain cognitive shifts.

It’s often compared to the Rubin Vase (the one that looks like two faces or a candlestick) or the Necker Cube. But there is something more visceral about the woman. Maybe it's because we are social animals. We care about faces. We care about age. We care about the "story" we see in those eyes.

👉 See also: Dr Dennis Gross C+ Collagen Brighten Firm Vitamin C Serum Explained (Simply)

Some therapists use the image to explain the concept of Cognitive Reframing. The idea is simple: just because you see the "old woman" doesn't mean the "young woman" isn't there. Both truths exist at once. It’s a powerful metaphor for conflict resolution. If two people look at the same set of facts and see two completely different things, who is right?

Both. Neither. It depends on the "flip."

How to Force Your Brain to Switch

If you are stuck on one version, try these specific triggers to break the neural loop:

- Focus on the Ear: If you see the young woman, look at her ear. Now, imagine that ear is an eye looking to the left. The rest of the old woman’s face should fall into place.

- Look at the Neck: The young woman’s necklace is the old woman’s mouth. Stare at that specific line and imagine a thin, straight mouth.

- The Big Nose: If you only see the old woman, look at her giant nose. Now, pretend that "nose" is actually a cheek and a jawline turned away from you.

Moving Toward Actionable Insights

So, what do you actually do with this information? It’s more than just a "fun fact" for your next trivia night. Understanding how your brain handles the old woman and young woman picture can actually change how you interact with the world.

First, acknowledge your Own-Age Bias. Realize that your brain is naturally tuned to prioritize people who look like you. This shows up in job interviews, social settings, and even how we consume news. When you catch yourself making a snap judgment about someone's "vibe," remember the illusion. You might be missing an entire perspective simply because your brain hasn't "flipped the switch" yet.

Second, use this as a tool for Empathy Practice. Next time you are in a heated argument where both sides seem to be looking at the same facts but reaching different conclusions, visualize the drawing. Ask yourself: "Am I looking at the nose or the jawline?" It reminds you that reality is often a matter of which features you choose to emphasize.

Finally, keep your brain "plastic." Look for other ambiguous figures like the Rabbit-Duck illusion or the Spinning Dancer. Regularly challenging your brain to see things from multiple angles isn't just a game—it’s cognitive exercise that helps maintain mental flexibility as you age.

The next time you scroll past this classic image, don't just dismiss it. Stop. Look. Wait for the flip. It’s a reminder that the world isn't always what it seems at first glance, and our brains are constantly making choices for us that we aren't even aware of.