Imagine standing in a line that stretches further than you can see. It is September 16, 1893. The heat is oppressive. Dust kicks up in choking clouds every time a horse shifts its weight or a wagon wheel creaks. You’re looking out over six million acres of tallgrass prairie, and you’re waiting for a single gunshot to change your life. This wasn’t just a race; it was the Oklahoma Land Run of 1893, and honestly, it was way more chaotic than the history books usually let on.

Most people think of the 1889 run when they hear about Oklahoma. That was the "big one" in popular culture, but the 1893 event—the opening of the Cherokee Outlet—was actually the largest. Over 100,000 people showed up. They were desperate. They were hopeful. And a lot of them were prepared to cheat.

Why the Cherokee Outlet was a massive deal

The Cherokee Outlet was a 58-mile wide strip of land running along the border of Kansas. For years, the Cherokee Nation had used it as a buffer zone and a place for grazing cattle. But the U.S. government, pressured by white settlers and the "Boomer" movement, eventually pressured the Cherokee to sell the land for roughly $8.5 million. It was a staggering amount of territory. We’re talking about land that would eventually become Kay, Grant, Alfalfa, Woods, Harper, Woodward, Major, Noble, Pawnee, and Ellis counties.

Basically, the government was trying to solve an economic crisis with dirt. The Panic of 1893 had hit, and people were broke. Families were starving in the East and Midwest. The promise of 160 acres of free land (provided you could "prove up" the claim by living on it and improving it) was the ultimate 19th-century stimulus package.

The "Sooners" and the systemic chaos of the start line

You’ve probably heard the term "Sooner." Today, it’s a proud mascot for the University of Oklahoma. Back in 1893? It was a slur. A Sooner was someone who snuck across the line before the official noon start time to stake a claim. They hid in creek beds, tall grass, or buffalo wallows. When the legitimate racers arrived on their exhausted horses, they’d find a Sooner already sitting there, tea brewing, acting like they’d been there for hours.

🔗 Read more: At Home French Manicure: Why Yours Looks Cheap and How to Fix It

The sheer scale of the fraud was a mess.

Government officials tried to prevent it by requiring everyone to register at booths beforehand. But the registration process was a disaster. At places like Arkansas City and Caldwell, Kansas, the lines for the booths were miles long. People stood in the sun for days. Some literally died of heatstroke or dehydration before the race even began. If you didn't have a registration certificate, you weren't supposed to be allowed to claim land, but in the frantic rush of 100,000 people, the rules mostly flew out the window.

What actually happened when the gun went off

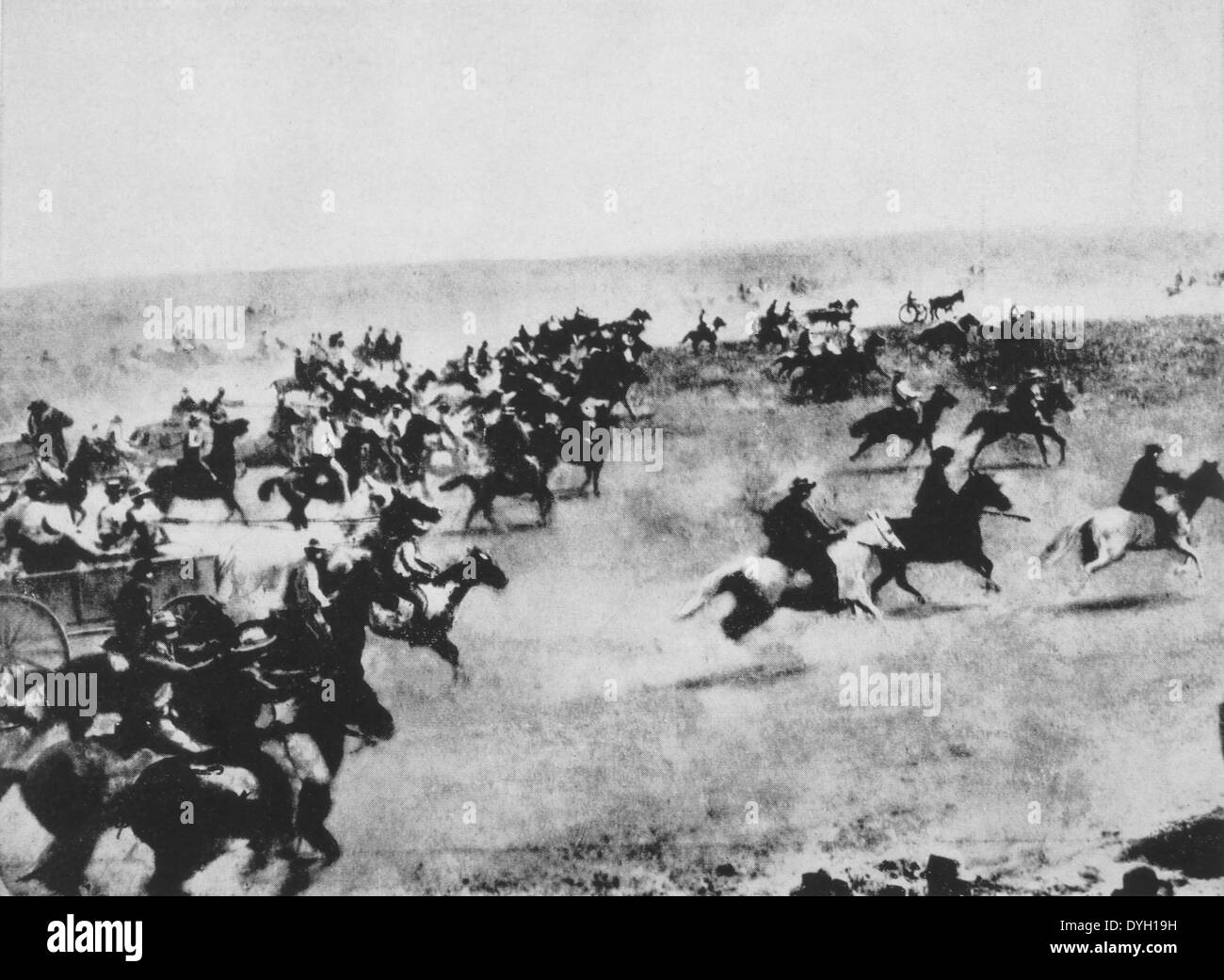

At high noon, the cavalry fired their pistols. It wasn't a clean start. It was a stampede.

Men and women on horseback took off at a dead gallop. Wagons jolted across the uneven prairie, often flipping over and crushing the occupants. People even hopped on trains. The Santa Fe Railway was allowed to run trains through the Outlet during the run, but they had to go slow—about 15 miles per hour—to keep things "fair." People were hanging off the sides, jumping from moving cars to get to a choice plot of land near a water source.

💡 You might also like: Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen Menu: Why You’re Probably Ordering Wrong

The noise must have been deafening. The sound of thousands of hooves, the shouting, the cracking of whips. And then there was the dust. The late summer had been dry. The topsoil was whipped into a frenzy, blinding the riders. You couldn't see ten feet in front of you. If your horse tripped in a prairie dog hole, you were done.

The immediate aftermath: Tent cities and water wars

By nightfall on September 16, cities existed where there had been nothing but grass that morning. Enid and Perry were the biggest. Within hours, these places had thousands of residents, makeshift "streets," and zero infrastructure.

Water was the biggest problem. If you didn't claim a spot near a creek or a spring, you were in trouble. In Perry, people were reportedly selling cups of muddy water for the price of a full meal. There were no trees for shade. People slept in their wagons, under their horses, or just in holes they dug in the ground to escape the wind.

It’s also worth noting the tension between the settlers and the African American participants. Many Black families, some of whom were former slaves of the Five Tribes or migrants from the South, participated in the run seeking a "Land of Canaan" where they could own property and escape Jim Crow. While some succeeded in establishing all-Black townships like Langston (founded during earlier openings), the 1893 run was fraught with racial hostility as white settlers competed for the same limited resources.

📖 Related: 100 Biggest Cities in the US: Why the Map You Know is Wrong

The reality of "Proving Up"

Getting the land was only the first step. To actually own it under the Homestead Act, you had to:

- Build a permanent structure (often a "soddy" made of literal bricks of grass because there was no timber).

- Cultivate the land.

- Live there for five years.

Many people didn't make it. The "Great American Desert," as some called it, was brutal. The winters were freezing, the summers were scorching, and the locusts were relentless. A huge percentage of the 1893 claimants abandoned their land within the first two years, selling out to neighbors or just heading back East with their tails between their legs.

Why this history matters to you today

The Oklahoma Land Run of 1893 was the literal end of the American Frontier. It was the moment the "safety valve" of the West officially closed. It also marked a tragic turning point for Native American sovereignty, as the "surplus" lands were stripped from tribal control to satisfy the hunger of a growing United States.

If you’re researching your genealogy or visiting Oklahoma, understanding the 1893 run is essential for context. It explains why the town layouts in Northern Oklahoma are so grid-like and why certain families have held onto the same patches of dirt for over 130 years.

How to explore this history yourself

If you want to see what this was actually like, don't just read a book. Go see the physical remnants of the era.

- Visit the Cherokee Strip Regional Heritage Center in Enid. They have an incredible collection of original artifacts, including a US Land Office from the 1893 run. It’s one of the few places where you can actually stand in the space where those frantic claims were filed.

- Check out the Sod House Museum in Aline. It’s the only original sod house built by a homesteader that is still standing. It’s encased in a building now to protect it from the elements, but it gives you a visceral sense of how small and cramped life was for those early settlers.

- Search the BLM General Land Office Records. If you think your ancestors were part of the 1893 run, you can search the federal land patents online. You’ll be able to see the exact legal description of their homestead and the date the title was finalized.

- Drive the "Old Chisholm Trail." Many of the routes used by the riders followed older cattle trails. Driving through the rolling hills of the Cherokee Outlet today still gives you a sense of the vastness that those riders faced with nothing but a horse and a canteen.

The 1893 Land Run wasn't just a race; it was a desperate gamble. For some, it was the birth of a legacy. For others, it was a fast track to ruin. Understanding the grit—and the greed—of that day is the only way to truly understand the spirit of the Southern Plains.