It was 1982. A skinny kid from a band called Samson had just stepped into the spotlight, replacing a fan favorite who couldn't keep his life together. No one really knew if it would work. Then, the needle dropped on The Number of the Beast.

The world changed.

Metal changed.

If you grew up in the eighties, or even if you're just finding this stuff on Spotify now, you know that scream. You know the one—the high-pitched, glass-shattering wail at the beginning of the title track. That was Bruce Dickinson introducing himself to the world. It wasn't just a vocal warm-up; it was a hostile takeover of the entire heavy metal genre. Honestly, people forget how much was riding on this record. Iron Maiden had two solid albums under their belt with Paul Di'Anno, but they were leaning more toward a punk-infused street metal sound. This was different. This was operatic, grand, and, according to some very confused people in the US, apparently satanic.

The reality is way more interesting than some "Satanic Panic" nonsense.

The Bruce Dickinson Gamble and the Birch Factor

Steve Harris is the heartbeat of Maiden. He’s the guy who writes the gallops, the lyrics about history, and the intricate bass lines that make your fingers hurt just listening to them. But even Steve knew they needed a shift. Di’Anno was great, but he didn't have the range to take the band where Harris wanted to go: into the stratosphere.

Enter "The Air Raid Siren."

👉 See also: Charlie Charlie Are You Here: Why the Viral Demon Myth Still Creeps Us Out

When Dickinson joined, the dynamic shifted instantly. He brought a theatricality that changed their stage presence forever. But we have to talk about Martin Birch. The producer. The guy who worked with Deep Purple and Black Sabbath. Birch was the one who famously made drummer Clive Burr play the intro to "The Prisoner" over and over again for hours until it was perfect. He pushed them. He made them sound massive. Without Birch’s crisp, punchy production, The Number of the Beast might have just been a collection of good songs. Instead, it became a sonic benchmark.

Did you know the title track was inspired by a nightmare? Steve Harris watched Damien: Omen II and later had a dream about being in a dark place with creepy figures. He woke up and started writing. It wasn't some ritualistic invocation; it was a guy reacting to a scary movie. Yet, when the album hit the shelves, people were literally burning the records in the streets of America. Talk about free marketing. The band basically laughed all the way to the bank while the protesters gave them more publicity than their label ever could have bought.

Not Just "The Hits": The Deep Cuts That Define the Record

Everyone talks about "Run to the Hills." It’s the radio staple. It’s the song your uncle knows. And yeah, it’s a masterpiece of songwriting—specifically that back-and-forth perspective between the invading cavalry and the indigenous people. It’s heavy, catchy, and has one of the best choruses in history.

But look closer.

"Hallowed Be Thy Name" is arguably the greatest heavy metal song ever written. Period.

It starts with that somber, lonely bell. Then the guitar harmony kicks in. Dickinson begins the narrative of a man walking to the gallows, questioning his faith and the meaning of life. The tempo shifts are insane. The way the song builds from a dirge into a frantic, galloping race toward the end is a masterclass in composition. It’s seven minutes of pure adrenaline and philosophy. If you haven't sat down with headphones and really listened to the dual guitar work between Dave Murray and Adrian Smith on this track, you’re missing out on the DNA of the genre.

✨ Don't miss: Cast of Troubled Youth Television Show: Where They Are in 2026

Then there’s "22 Acacia Avenue." It’s a sequel to "Charlotte the Harlot" from the first album, but it’s so much more musically complex. The riffing is jagged and uncomfortable in the best way possible. It shows a band that wasn't afraid to be weird. They weren't just writing pop songs with distortion; they were writing mini-epics.

The Controversy That Backfired

The "satanic" label was the best thing that ever happened to Iron Maiden.

During the Beast on the Road tour, religious groups would stand outside venues with signs. They’d hold "record smashings." Sometimes they’d bring a steamroller to crush copies of The Number of the Beast. The irony? Most of the people protesting hadn't actually read the lyrics. If they had, they would have realized "The Number of the Beast" is a story about a guy who is scared of the devil, not worshiping him.

The intro of the song features a quote from the Book of Revelation. The band actually wanted a famous horror actor to read it—Vincent Price. But Price wanted too much money (reputedly £25,000), so they hired a session actor named Barry Keeffe who did a "Vincent Price voice." It worked perfectly. It sounded ancient, foreboding, and just theatrical enough to scare the living daylights out of parents in the suburbs.

Why the Production Still Holds Up

Listen to a lot of metal from 1982 and it sounds thin. The drums sound like tin cans, or the bass is buried so deep you can’t find it with a shovel. The Number of the Beast avoids that.

Clive Burr’s drumming on this record is often overshadowed by Nicko McBrain’s later work, but Burr was a powerhouse. His style was more "rock and roll" and swing-heavy. Listen to the opening of "Gangland." It’s jazzy, fast, and aggressive. The mix allows every instrument to breathe. You can hear Harris’s bass clacking against the frets—that signature "clank" that became the blueprint for thousands of bassists.

🔗 Read more: Cast of Buddy 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

The twin-guitar attack of Smith and Murray also found its footing here. Dave Murray has that fluid, legato style that sounds like liquid silk. Adrian Smith is the architect, the guy with the melodic, structured solos. The contrast between them is what gives Maiden their texture. On tracks like "Children of the Damned," inspired by the movie Village of the Damned, you hear that delicate acoustic opening before the wall of sound hits. It’s dynamic. It isn't just "loud" the whole time.

The Cultural Footprint

This album didn't just top the UK charts; it broke the band in America. It proved that you could be uncompromisingly heavy and still have a sense of melody. It influenced everyone from Metallica to Avenged Sevenfold. Without "The Number of the Beast," the "New Wave of British Heavy Metal" might have remained a localized UK phenomenon.

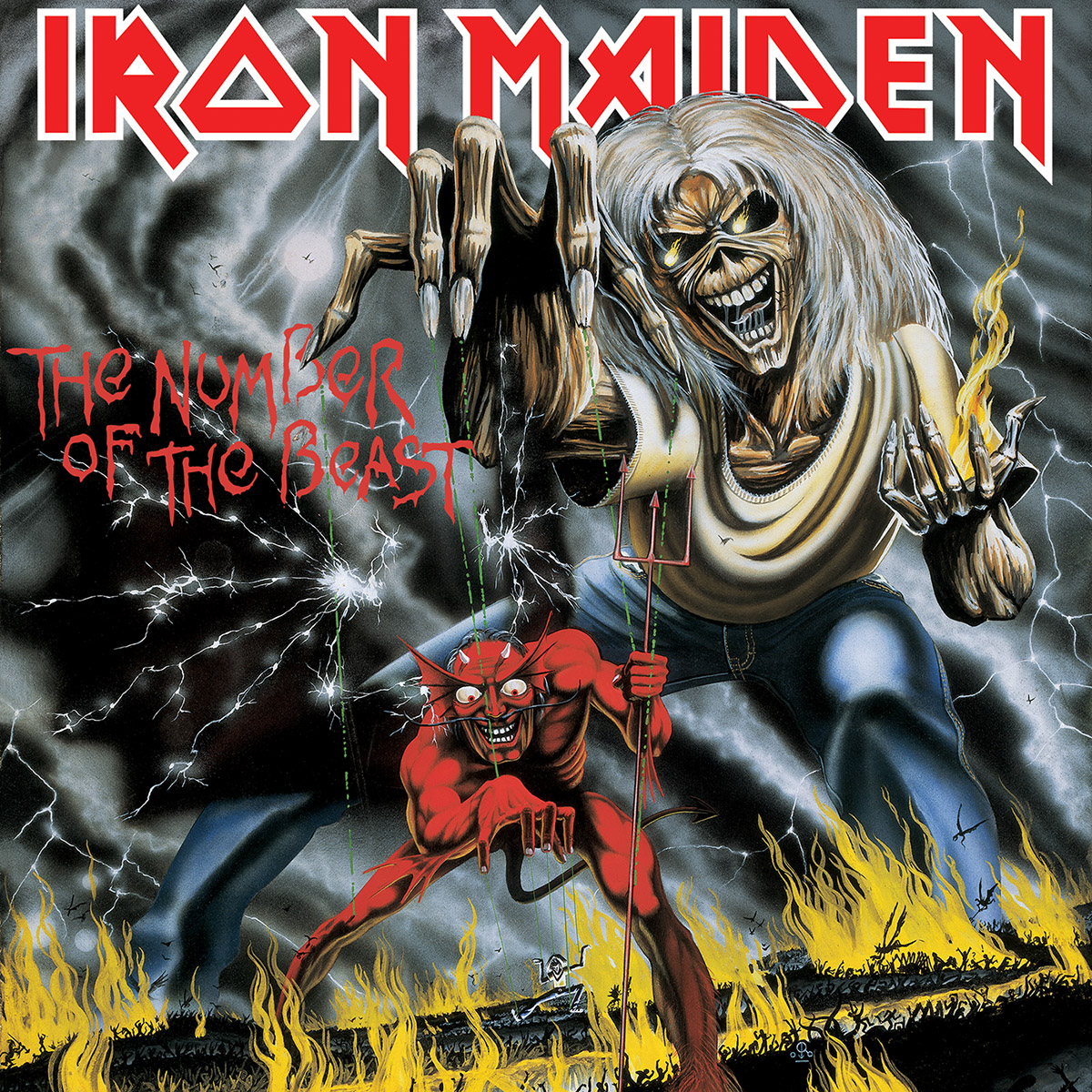

It also gave us Eddie in his most iconic form. Derek Riggs, the artist behind the covers, outdid himself. Eddie as a puppet master controlling the devil, who is in turn controlling a smaller Eddie? It’s genius. It’s the kind of imagery that made you buy the t-shirt before you even heard the music.

How to Experience the Album Today

If you’re revisiting this record, don’t just play it in the background while you’re cleaning the house. It’s too dense for that.

- Find a high-quality press or a lossless stream. The nuances in the guitar harmonies get lost in low-bitrate MP3s.

- Listen to "Hallowed Be Thy Name" last. It was designed to be the closer (well, technically "Total Eclipse" was added in later versions, but "Hallowed" is the emotional finale).

- Pay attention to the lyrics. Steve Harris is a history and film buff. Look up the references to the 1960s TV show The Prisoner. It adds a whole new layer to the listening experience.

- Compare it to "Killers". Notice the jump in ambition. It’s like watching a band go from a local garage to an arena in the span of twelve months.

The Number of the Beast isn't just a heavy metal album. It’s a cultural touchstone that proved heavy music could be intelligent, theatrical, and commercially massive without selling its soul. Decades later, the gallop is still just as infectious as it was in '82.

To truly appreciate the legacy, track down the 2022 40th-anniversary vinyl release. It actually restores "Total Eclipse" to the tracklist in place of "Gangland," which is how Steve Harris originally wanted it. Listening to the album with that specific flow changes the energy of the second half significantly. Once you’ve mastered the studio versions, look up the live recordings from the Hammersmith Odeon in 1982. Hearing Bruce Dickinson hit those notes live, without the safety net of a studio, is the final proof that Iron Maiden was—and is—in a league of their own.