You probably remember that poster from middle school biology. The one with the bright purple bean sitting in the middle of a cell, labeled "The Brain of the Cell." Honestly? That’s a bit of a lazy metaphor. If you really want to understand what is the nucleus, you have to stop thinking of it as a bossy manager and start seeing it as a high-security library containing the only blueprints for a skyscraper that’s constantly under construction. It doesn't just "sit there." It's a chaotic, vibrating hub of activity that determines whether you have blue eyes, how you recover from a workout, and, unfortunately, how diseases like cancer gain a foothold in the body.

Every single one of your trillions of cells—well, almost all of them—houses this structure. It’s tiny. We’re talking about something roughly six micrometers in diameter. To put that in perspective, you could fit about ten nuclei across the width of a single human hair. Yet, inside that microscopic speck, there are two meters of DNA crammed and folded with the precision of a master origami artist. If that folding goes wrong by even a fraction, things fall apart fast.

What is the nucleus actually doing in there?

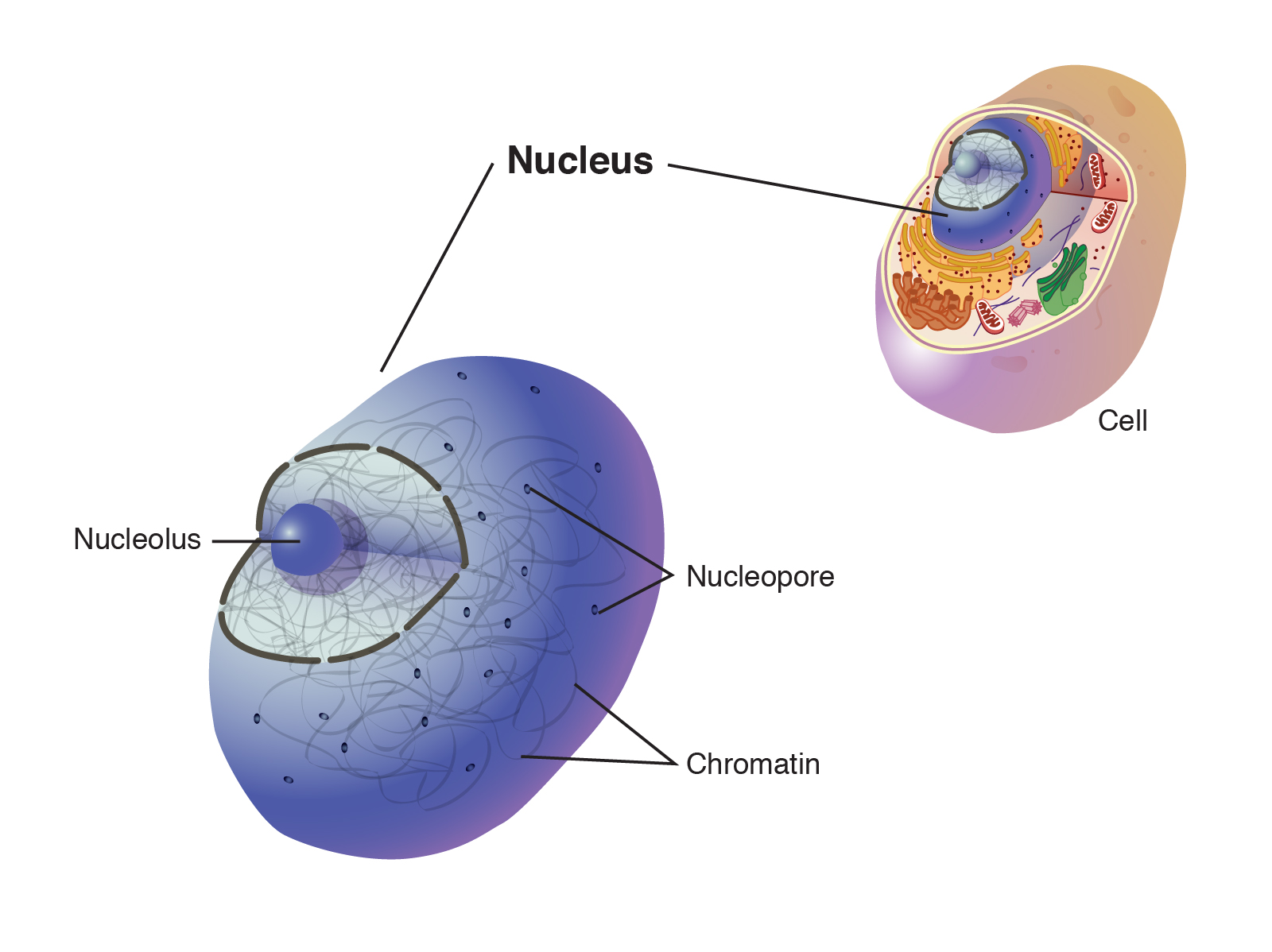

Think about the sheer logistics. Your DNA is the instruction manual for building proteins. But the machines that actually build those proteins, the ribosomes, live outside the nucleus in the cytoplasm. The nucleus acts as a gatekeeper. It doesn't let the DNA leave—that would be too risky. Instead, it makes a "photocopy" called mRNA and spits it out through tiny holes called nuclear pores.

👉 See also: Why Saying Let's Have Sex Matters More Than You Think

These pores are basically the bouncers of the cellular world. They are incredibly picky. They allow small molecules to zip in and out, but larger proteins need a specific "VIP pass" (a nuclear localization signal) to get through. It’s a constant, frantic exchange. Thousands of signals per second are flying across that membrane, telling the nucleus to turn specific genes on or off based on whether you just ate a sandwich, ran a mile, or caught a virus.

Robert Brown, a Scottish botanist, was the first to really call attention to this "areola" or nucleus back in 1831 while looking at orchids. He didn't quite realize he was looking at the control center of life; he just noticed it was a consistent feature. We’ve come a long way since then. We now know that the nuclear envelope—the double membrane surrounding the stuff—is physically connected to the rest of the cell's internal plumbing, specifically the endoplasmic reticulum. It’s all one big, interconnected factory.

The stuff inside: Chromatin and the Nucleolus

If you cracked a nucleus open, you wouldn't find a soup. You'd find chromatin. This is DNA wrapped around proteins called histones. Imagine taking a massive ball of yarn and wrapping it tightly around spools so it doesn't get tangled. That's the only way two meters of genetic material fits into a space that small.

Then there’s the nucleolus. This is the dark spot you see in microscope photos. It’s not a separate room; it’s more like a dense crowd in a subway station. This is where ribosomes are manufactured. If a cell needs to grow fast—like a muscle cell after a heavy lift or, more dangerously, a tumor cell—the nucleolus gets huge because it’s cranking out ribosome parts at a breakneck pace.

Not every cell plays by the same rules

Biology loves an exception. While we say the nucleus is the "heart" of the cell, some cells decide they don't need one. Your red blood cells, for instance, dump their nuclei as they mature. Why? Space. They need every available millimeter to carry oxygen. Because they lack a nucleus, they can't repair themselves or divide. They live for about 120 days and then they’re done.

On the flip side, look at your skeletal muscle cells. These are massive, long fibers. A single nucleus wouldn't be enough to manage the protein needs of such a large area, so muscle cells are "multinucleated." They have hundreds of nuclei scattered along their length, acting like local branch managers for a massive corporation.

When the control center breaks down

Understanding what is the nucleus becomes a lot more urgent when we talk about aging and disease. Progeria, a rare condition that causes children to age rapidly, is caused by a glitch in a protein called Lamin A. This protein provides the structural scaffolding for the nucleus. When it's defective, the nucleus becomes misshapen and "blebs" out. The DNA inside gets damaged, the cell can't function, and the body literally wears out decades before its time.

Cancer is another "nuclear" problem. Oncologists often look at the size and shape of a nucleus to determine how aggressive a cancer is. In healthy cells, the nucleus is usually nice and round. In many cancers, it becomes jagged, enlarged, and packed with extra sets of chromosomes. It’s a visual representation of a system that has lost its internal regulations.

The Nuclear Envelope: A double-edged sword

The double membrane of the nucleus is a brilliant evolutionary invention. It protects our precious genetic code from the chemical chaos of the cytoplasm. However, it also creates a lag time. In bacteria, which have no nucleus, DNA is just floating around. They can respond to changes in their environment almost instantly. In humans, we have to wait for that mRNA to be transcribed, processed, and exported. It’s slower, but it allows for much more complex regulation. This complexity is why you can have the same DNA in a brain cell and a skin cell, but have them look and act completely differently. The nucleus decides which parts of the manual to read.

Practical ways to support your cellular health

You can't exactly "scrub" your nuclei, but you can influence how they function. Epigenetics is the study of how your environment changes which genes your nucleus decides to use.

- Prioritize Sleep: Research from institutions like the University of Rochester suggests that the brain’s waste-clearance system is most active during sleep. While this focuses on the space between cells, the cellular stress reduced by sleep directly impacts the integrity of nuclear membranes and DNA repair mechanisms.

- Manage Oxidative Stress: Free radicals are unstable molecules that can punch holes in cell membranes and damage DNA. Eating a variety of colorful vegetables provides the antioxidants needed to neutralize these "bullies" before they reach the nuclear envelope.

- Keep Moving: Regular exercise triggers signaling pathways that tell the nuclei in your mitochondria (the cell's power plants) to multiply and become more efficient. Yes, mitochondria have their own tiny bits of DNA, but they still rely on the "main" nucleus for most of their instructions.

- Avoid Known Mutagens: This sounds obvious, but UV radiation and certain chemicals physically break the DNA strands inside the nucleus. Your cells have "repair crews" (like the p53 protein), but they can only do so much. Don't overwork the maintenance staff.

The nucleus is the most sophisticated filing system in the known universe. It’s a dynamic, shifting, and incredibly crowded place where the instructions for you are guarded and executed every second of every day. By understanding that this isn't just a static "brain," but a living gatekeeper, we get a much clearer picture of how our lifestyle choices filter down to the microscopic level.

To truly protect your genetic integrity, focus on reducing chronic inflammation, which is the primary driver of nuclear stress. Start by replacing highly processed seed oils with stable fats like olive oil and ensuring your Vitamin D levels are optimized, as Vitamin D acts as a hormone that directly enters the nucleus to influence gene expression across thousands of sites. Monitoring these biomarkers through regular blood work is the most effective way to see if your "command center" is operating in a clean environment.