Ground zero. It's a term we use for everything now—failed startups, bad breakups, the center of a flu outbreak. But the origin is terrifying. When you pull up a nuclear bomb blast radius map, you aren't just looking at circles on a screen. You're looking at the calculated dismantling of a city. Honestly, most people get this wrong because they expect a clean circle of fire like in the movies. Reality is messier. It's about air pressure, thermal radiation, and whether you happen to be standing behind a very thick concrete wall at 8:15 AM.

Physics doesn't care about cinematic timing.

If you’ve spent any time on NUKEMAP—the tool created by historian Alex Wellerstein—you’ve seen the primary colors of doom. Yellow is the fireball. Red is the heavy blast damage. Green is the radiation. It looks like a target, but that’s a simplification for the sake of our sanity. In a real-world scenario, the topography of a place like San Francisco or Pittsburgh would warp those circles into jagged, unpredictable shapes. Buildings create "shadows" from the thermal pulse. Hills deflect the shockwave.

How a Nuclear Bomb Blast Radius Map Actually Works

Most people think the biggest threat is the fireball. It’s not. Unless you are standing directly at the point of detonation, the fireball is relatively small compared to the total area of effect. The real killer is the overpressure.

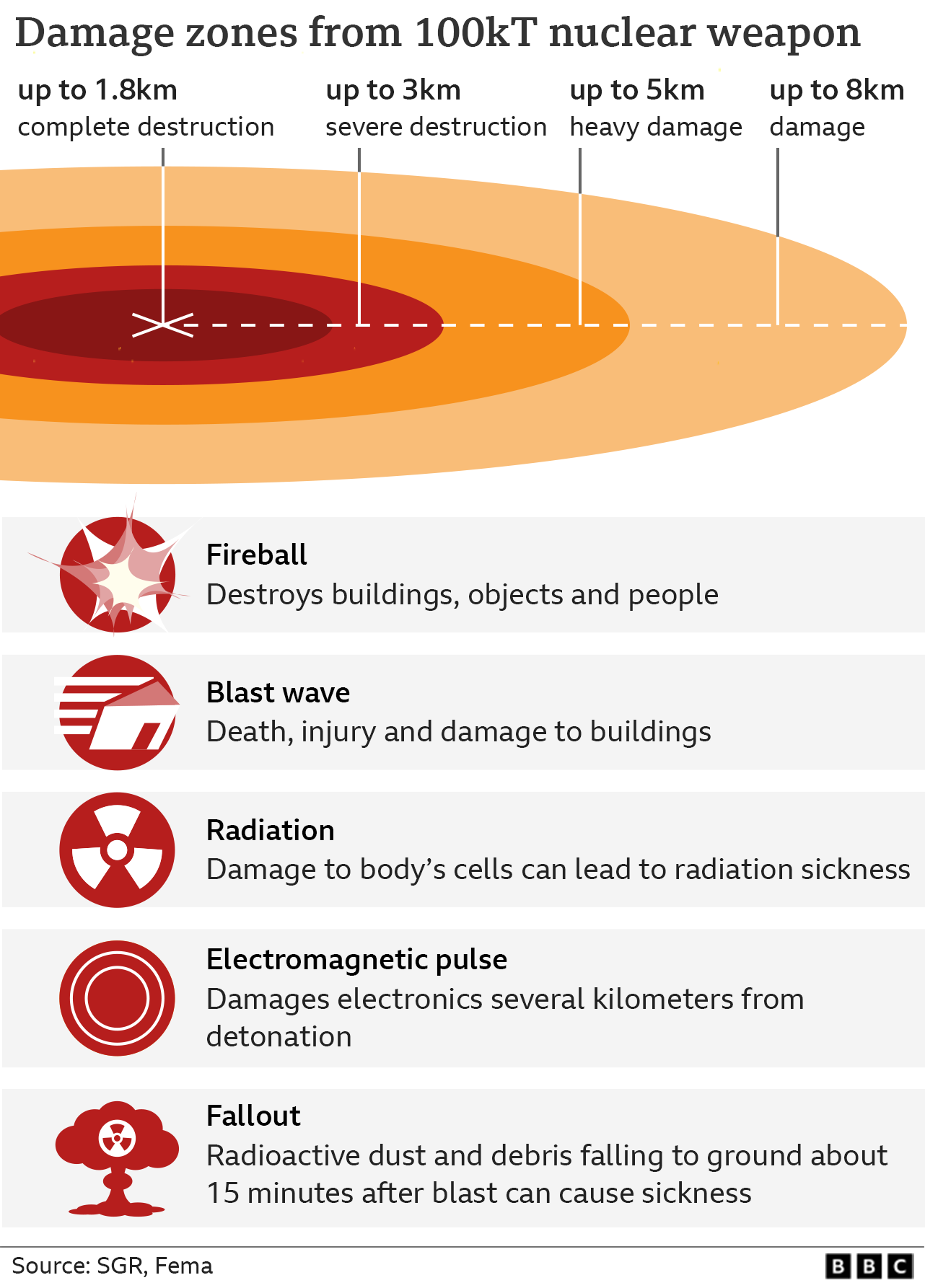

Think of the air around you. Right now, it’s at a standard pressure. When a nuclear weapon goes off, it compresses that air into a physical wall that moves faster than the speed of sound. This is the "blast wave." On a nuclear bomb blast radius map, this is usually divided into zones measured in pounds per square inch (psi).

If you're in the 20 psi zone, heavy concrete buildings are flattened. It doesn't matter how well-built your house is; it becomes toothpicks. As you move further out to the 5 psi zone, the pressure is lower, but the wind speeds are still hitting several hundred miles per hour. This is where most fatalities happen. It's not the radiation that gets you first—it's the fact that the office building across the street just turned into a billion glass shards flying at your face.

The Thermal Pulse: Fire Without a Flame

Before the wind hits, there is the light. A nuclear detonation produces a pulse of thermal radiation so intense it can ignite fires miles away from the actual explosion.

If you’re looking at a nuclear bomb blast radius map for a 1-megaton weapon (which is much larger than the Hiroshima bomb but standard for some modern warheads), the third-degree burn radius can extend over 10 miles. That's a massive area. We are talking about skin being charred instantly before you even hear the "boom." Interestingly, the color of your clothes matters here. Darker fabrics absorb more thermal energy. Lighter colors reflect it. It's a small, weird detail that survivalists obsess over, though if you're close enough for your shirt color to matter, you have much bigger problems.

Why Altitude Changes Everything

Here is the thing: a bomb hitting the ground is "wasted" energy.

When a weapon is detonated as a "ground burst," it digs a massive crater and kicks up tons of dirt. This dirt becomes highly radioactive and falls back down as fallout. But if you want to destroy a city, you use an "air burst." By exploding the weapon a few thousand feet in the sky, the blast wave reflects off the ground and combines with itself. This is called the Mach stem. It essentially doubles the destructive power of the pressure wave across the surface of the city.

This is why a nuclear bomb blast radius map usually has a toggle for "height of burst." If you set it to the surface, the "heavy damage" circle shrinks, but the "long-term poison" (fallout) area grows. If you set it for maximum blast effect, the city is leveled, but the radioactive fallout is actually significantly less because the fireball never touched the ground to suck up the dust. It’s a grim trade-off that military planners have spent decades perfecting.

The Hiroshima Benchmark vs. Modern Warheads

We always go back to "Little Boy." It was a 15-kiloton weapon. By modern standards, that’s a "tactical" nuke. It's small.

When you look at a nuclear bomb blast radius map for a modern Russian RS-28 Sarmat (Satan II), the scale is almost impossible to comprehend. We aren't talking about a few blocks in Lower Manhattan. We are talking about the entire New York metropolitan area being engulfed in the 5 psi blast zone. The "light damage" radius, where windows shatter and people are injured by flying debris, could stretch into the suburbs of New Jersey and Connecticut.

- 15 kt (Hiroshima): Fireball radius of about 200 yards.

- 800 kt (Modern Topol-M): Fireball radius of nearly a mile.

- 50 mt (Tsar Bomba): Fireball radius of 3 miles and total destruction for 20+ miles.

The Tsar Bomba was the largest ever tested. The flash was visible 600 miles away. It's the outlier, but it shows the upper limit of what physics allows. Most modern strategic warheads are in the 300 to 800 kiloton range because it’s more "efficient" to hit a target with several smaller bombs than one giant one.

Radiation: The Invisible Border

Radiation is the most misunderstood part of the map. On a nuclear bomb blast radius map, you’ll see a small circle near the center labeled "500 rem" or "5 Sieverts." If you are in that circle, you have a 90% chance of dying within a few weeks.

But here’s the kicker: if you are close enough to get a lethal dose of initial radiation, you are almost certainly already dead from the blast or the heat. The "prompt radiation" doesn't travel as far as the pressure wave. The real radiation threat is the fallout, which isn't a circle at all. It’s a cigar-shaped plume that follows the wind.

If the wind is blowing at 15 mph toward the northeast, your nuclear bomb blast radius map suddenly becomes a long, terrifying streak across the map. This stuff can settle hundreds of miles away. It looks like ash or sand. It’s not "glowing" green. It’s just dust that emits gamma rays.

Dealing with the "Shadow Effect"

Urban geography changes the map. If you are in a "canyon" of skyscrapers, the blast wave gets funneled. It moves faster and hits harder down the streets than it does if it were moving over an open field. Conversely, if you are behind a massive, reinforced concrete structure, you might survive a blast that kills someone a block away who was in the "line of sight" of the explosion.

Experts like Lynn Eden, author of Whole World on Fire, argue that federal agencies traditionally underestimated the damage from nuclear weapons because they focused on the blast and ignored the "mass fire." A nuclear bomb doesn't just knock things over; it turns a city into a self-sustaining firestorm. The heat is so intense that oxygen is sucked out of the surrounding areas to feed the flames. This happened in Hiroshima and Dresden (with conventional bombs). The nuclear bomb blast radius map doesn't always show the "fire zone," but it’s often larger than the blast zone itself.

Practical Realities of Mapping Risk

Why do we look at these maps? It’s usually a mix of morbid curiosity and a desire for some sense of control. If you know where the circles end, you can imagine being "safe" just outside the line.

But these maps are based on ideal conditions. They assume a flat surface. They assume the bomb goes off exactly where it was aimed. They don't account for "MIRVs" (Multiple Independently Targetable Reentry Vehicles), where one missile carries ten warheads that spread out like a shotgun blast.

If you are looking at a nuclear bomb blast radius map for emergency planning, the key isn't just seeing where the circles are. It’s understanding the timeline.

- Seconds 0-10: Thermal pulse and initial radiation. If you see the flash, drop and cover. Do not look at it. The light can blind you permanently from miles away.

- Seconds 10-60: The blast wave. It takes time to travel. If you are 5 miles away, you have about 20 seconds after the flash before the air hits you like a freight train.

- Minutes 15-60: Fallout begins to descend. This is when you need to be inside, ideally in a basement or the center of a large building.

Actionable Steps for Risk Assessment

Don't just stare at the circles. If you're using a nuclear bomb blast radius map to understand your environment, look at these specific factors:

👉 See also: Dr Dre Beats Serial Number Check: What Most People Get Wrong

- Identify Strategic Targets: Are you within 10 miles of a major communications hub, a military base (specifically SAC bases), or a major port? These are the "likely" centers of the circles.

- Know Your Prevailing Winds: In the US, weather generally moves West to East. If a target is West of you, you are in the "fallout shadow."

- Evaluate Building Material: Wood-frame houses are essentially kindling in the thermal zone and paperweights in the blast zone. Brick is better. Reinforced concrete is best.

- The "Rule of Thumb": If you see a mushroom cloud, hold out your arm and put your thumb over it. If the cloud is bigger than your thumb, you are in the danger zone for fallout and likely within the secondary blast zones.

The maps are tools for visualization, but they are also reminders of the sheer scale of energy we’ve learned to tap into. A 1-megaton blast is the equivalent of a million tons of TNT. Visualizing that on a map of your neighborhood is sobering. It’s meant to be. The math behind the nuclear bomb blast radius map is precise, but the human cost is immeasurable.

If you want to dive deeper, check out the Smyth Report or the FEMA archives on "Nuclear Attack Planning Factors." They aren't light reading, but they provide the raw data that these maps are built on. Understanding the physics won't stop the bomb, but it strips away the Hollywood myths and replaces them with cold, hard reality.