It’s almost a seasonal law now. Every October through December, you see the spindly silhouette of Jack Skellington plastered on everything from high-end slow cookers to dog sweaters. We associate it so deeply with one specific name that the full title is literally The Nightmare Before Christmas Tim Burton. But here’s the thing that still trips people up: Tim Burton didn’t actually direct it.

Henry Selick did.

That’s not a slight against Burton. The man’s DNA is all over the celluloid. He wrote the original three-page poem in 1982 while working as an animator at Disney. He designed the characters. He produced the thing. But he was busy filming Batman Returns and Ed Wood while a crew of dedicated animators spent three years in a dark warehouse in San Francisco moving tiny puppets frame by painful frame. If you want to understand why this movie still dominates the cultural zeitgeist decades later, you have to look past the branding and into the messy, risky, and borderline miraculous production that almost stayed locked in the Disney vaults.

The Disney Rejection That Started Everything

Back in the early 80s, Tim Burton was the weird kid at Disney. He was working on films like The Fox and the Hound, which, if you know his style, was a terrible fit. While the rest of the studio was drawing cute forest animals, Burton was sketching a skeletal Pumpkin King and his ghost dog, Zero. He pitched it as a TV special or a short film. Disney hated it. Well, maybe "hated" is too strong, but they definitely didn't get it. They thought Jack Skellington was too scary for kids. They shelved it.

Burton left Disney, became a massive success with Beetlejuice and Batman, and suddenly, the "weird kid" had leverage. Disney realized they still owned the rights to his old poem. They saw an opportunity to capitalize on the "Burton Brand," but they were still terrified of the content. Honestly, the studio was so worried about the brand image that they released the film under their Touchstone Pictures banner instead of the main Disney name. They thought it might be too dark for the "Disney" label.

Why the Animation Style Matters More Than You Think

Stop-motion is a nightmare. Truly. For The Nightmare Before Christmas Tim Burton and Henry Selick demanded a level of fluidity that just hadn't been seen in the medium at that scale. We’re talking about 24 frames per second. Each second of film required 24 individual shifts of a puppet’s position. If a rigger bumped a tripod on Wednesday, the entire week’s work might be scrap.

🔗 Read more: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

Jack Skellington alone had around 400 different heads. Each head had a different expression to handle the phonetic requirements of Danny Elfman’s songs. When Jack sings "What's This?" the energy is frantic. The camera moves. That’s the part people forget—the camera isn't static. They used specialized rigs to move the camera through the miniature sets, which was a logistical feat that still holds up today even in the age of seamless CGI.

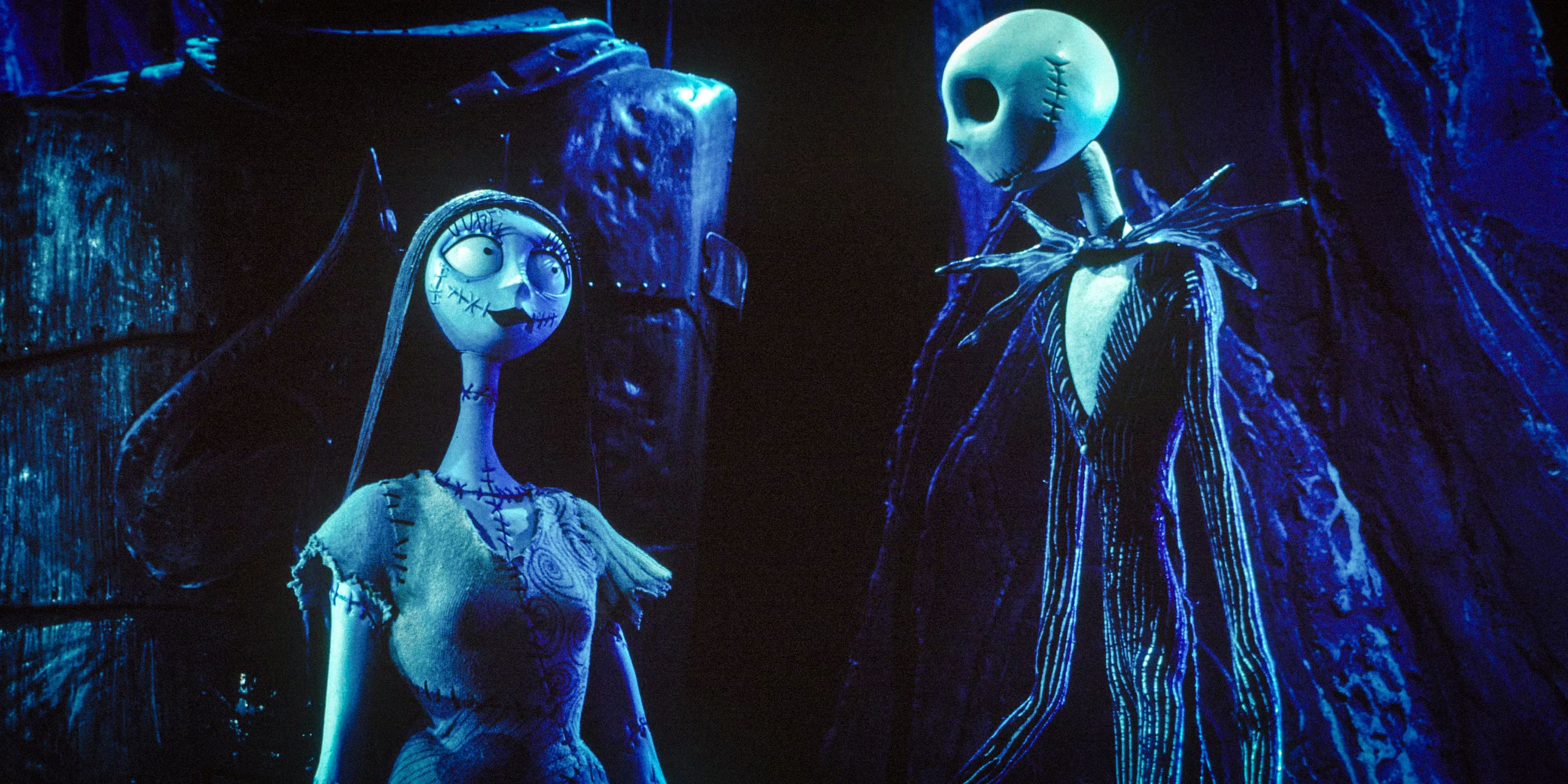

There’s a tactile grit to stop-motion. You can almost feel the texture of the burlap on Oogie Boogie or the coldness of the graveyard stone. CGI can't replicate that "uncanny valley" charm perfectly because CGI is too clean. Nightmare works because it feels like a toy box that came to life when you weren't looking. It’s slightly imperfect. It’s tangible.

The Danny Elfman Friction

You can’t talk about this movie without talking about the music. Danny Elfman and Tim Burton had a legendary partnership, but during the production of Nightmare, they actually had a massive falling out. It was so bad they didn't work together on Burton’s next film, Ed Wood.

Elfman didn't just write the songs; he was Jack Skellington. While Chris Sarandon provided the speaking voice, Elfman did the singing. He has stated in numerous interviews that he felt a deep, personal connection to Jack’s mid-life crisis—that feeling of being the best at what you do but still feeling empty inside.

The songwriting process was unconventional. Burton would describe the "feel" or a specific image from his poem, and Elfman would go off and compose. There wasn't even a finished script when most of the songs were written. The narrative was literally built around the music. This is why the film feels like an operetta. The songs don't just stop the plot for a dance number; they are the plot.

💡 You might also like: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

The "Scary" Factor and the Cult Following

When the movie finally hit theaters in 1993, it did okay. It wasn't a flop, but it wasn't the juggernaut it is now. It made about $50 million domestically. Respectable, sure. But the real explosion happened in the late 90s and early 2000s.

Why? Because it gave a voice to the "spooky" kids.

It’s a movie for people who feel like outsiders. Jack Skellington is the ultimate outsider—a man who tries to be something he’s not and fails spectacularly. Usually, in a movie, the hero succeeds in his quest. Jack doesn't. He tries to "do" Christmas, he ruins it, he gets shot down by the military, and he crashes in a cemetery. It’s a story about failing, accepting who you are, and finding value in your own niche. That resonates.

There’s also the "Holiday Limbo" factor. Is it a Halloween movie? Is it a Christmas movie? By being both, it occupies a six-month window of relevance every single year. Retailers like Hot Topic noticed this early. They leaned into the Jack and Sally aesthetic, and the merchandising revenue eventually dwarfed the original box office returns.

Common Misconceptions About the Film

- Tim Burton directed it: Again, no. Henry Selick directed. Burton was on set for maybe eight to ten days total over the course of the three-year production.

- It’s a kids’ movie: It’s rated PG, but the imagery is legitimately grotesque. Oogie Boogie is a sack full of bugs. Sally regularly sews her own limbs back on. It’s "family-friendly" in the way Grimm’s Fairy Tales are—it acknowledges that kids can handle a little darkness.

- The characters are 2D drawings: People often mistake the sharp, German Expressionist lines for traditional animation. Every single thing you see was a physical object in a room.

The Legacy of Halloween Town

The influence of The Nightmare Before Christmas Tim Burton helped usher in a new era for stop-motion. Without its success, we likely wouldn't have James and the Giant Peach, Coraline, or ParaNorman. It proved that there was a massive, untapped market for "creepy-cute."

📖 Related: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

Look at the lighting. The film uses heavy "Chiaroscuro" lighting—high contrast between light and dark. This was a direct callback to 1920s horror films like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. By bringing that high-art aesthetic to a "cartoon," the filmmakers created something that didn't age. If you watch it today on 4K Blu-ray, it looks like it could have been made yesterday.

How to Experience the Movie Like an Expert

If you’ve seen the movie a thousand times, you need to start looking at the background details. The level of "Easter eggs" is insane for a film made in 1993.

- Look for the Hidden Mickeys: Despite the "Touchstone" branding, the animators snuck in Disney nods. There’s a hidden Mickey in the steam from the scientist’s chemicals and another on a girl’s pajamas.

- The Cameos: The street musicians in Halloween Town are based on real-life people, including Danny Elfman’s face inside the upright bass.

- The Cat: The cat from Burton’s earlier short film Vincent makes a cameo.

- Watch the Shadows: In many scenes, the shadows don't behave naturally. They were often hand-painted or manipulated to look more menacing, a hallmark of the expressionist style Burton loves.

Practical Steps for Fans and Collectors

If you're looking to dive deeper into the world of Jack Skellington, don't just buy the standard merch. Look for the "Making Of" books from the original release. They detail the armature designs—the metal "skeletons" inside the puppets—which are masterpieces of engineering.

For those interested in the technical side, check out the 20th-anniversary behind-the-scenes features. They show the "replacement animation" technique used for Jack's mouth, which involved a literal library of hundreds of tiny mouthpieces filed in drawers.

Lastly, if you're a collector, be wary of "vintage" items. Because the movie has been re-released so many times, many items marketed as "original 1993" are actually from the 2003 or 2013 anniversary waves. Check the copyright stamps on the bottom of figures; the original Hasbro and Applause toys have very specific moldings that distinguish them from the newer NECA or Diamond Select versions.

The enduring power of this film isn't just about the aesthetic. It's about the fact that it was a "passion project" in the truest sense. It wasn't made by a committee to sell toys. The toys came because people fell in love with a skeleton who just wanted to feel something new. That kind of sincerity is hard to fake, and it’s why we’ll still be talking about it in another thirty years.