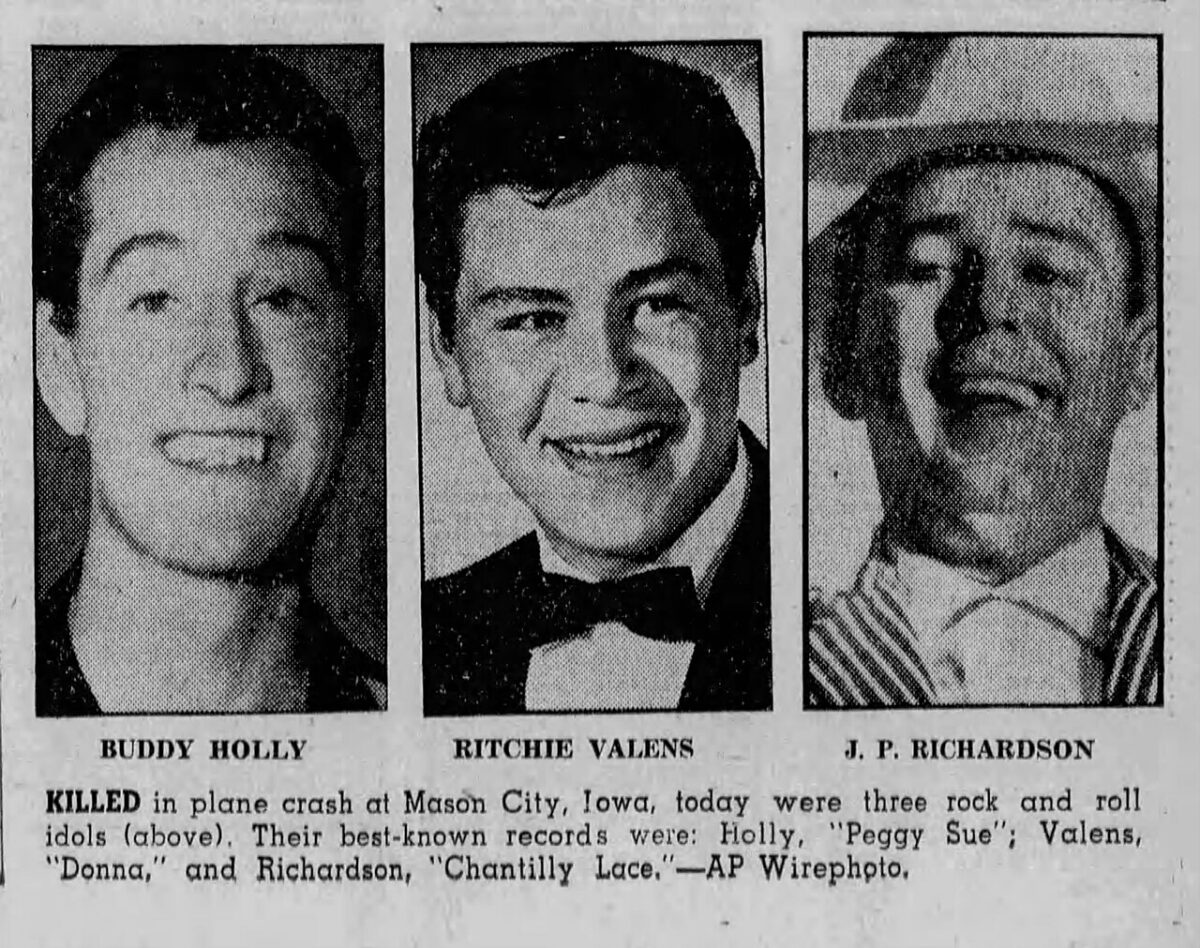

It was freezing. That’s the one thing everyone forgets when they talk about the Buddy Holly plane crash who died on that miserable February morning in 1959. We focus on the music, the black-rimmed glasses, and the "Day the Music Died" lyrics, but the reality was a bunch of shivering, exhausted musicians stuck in a bus with a broken heater. Their drums were literally freezing to the floorboards.

Buddy Holly was fed up. He was a 22-year-old superstar who just wanted clean laundry and a decent night's sleep before the next gig in Moorhead, Minnesota. He didn't want to die in a cornfield. He just wanted a shower.

The "Winter Dance Party" tour was a logistical nightmare from day one. The promoters had booked a zigzagging route across the Midwest in the dead of winter using school buses that were essentially rolling refrigerators. By the time they hit Clear Lake, Iowa, the drummer, Carl Bunch, had already been hospitalized with frostbite. Think about that for a second. A professional musician got frostbite inside a tour bus. It’s no wonder Buddy reached for his wallet and decided to charter a private plane.

The Fatal Decision at the Surf Ballroom

The show at the Surf Ballroom ended late. Buddy Holly approached Jerry Dwyer, who ran a local flying service, and shelled out $36 per person for a Beechcraft Bonanza. He wasn't supposed to be the only one on that plane. The original plan was for Buddy and his bandmates, Waylon Jennings and Tommy Allsup, to take the seats.

Fate is a weird thing.

Waylon Jennings, who would later become a country music legend, gave up his seat to J.P. "The Big Bopper" Richardson. The Bopper had the flu. He was a big guy, he was hurting, and he couldn't handle another night on that freezing bus. When Buddy found out Waylon wasn't flying, he joked, "Well, I hope your ol' bus freezes up." Waylon shot back, "Well, I hope your ol' plane crashes."

That sentence haunted Waylon Jennings for the rest of his life.

Then you had Ritchie Valens. He was only 17. He’d never been on a small plane before and was terrified of flying, but he also didn't want to ride that bus. He and Tommy Allsup flipped a coin. Ritchie won. He got the seat. He also got a one-way ticket to a cornfield outside of Mason City.

✨ Don't miss: Temuera Morrison as Boba Fett: Why Fans Are Still Divided Over the Daimyo of Tatooine

Roger Peterson: The Pilot Out of His Depth

We often blame the weather, but the investigation by the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) pointed a heavy finger at the pilot, 21-year-old Roger Peterson. He wasn't a bad pilot, but he was young. Crucially, he wasn't yet certified to fly by instruments alone (IFR).

He was used to flying by sight.

When the plane took off around 12:55 AM on February 3, 1959, the horizon was gone. A heavy snowstorm was blowing in, and the sky blended into the snowy ground. This is what pilots call "spatial disorientation."

The Sperry Gyroscope Trap

There’s a technical detail often missed in the casual retellings of the Buddy Holly plane crash who died that night. The Beechcraft Bonanza was equipped with a Sperry F-3 attitude indicator. In most planes Peterson had flown, the horizon line on the gauge moves one way to indicate a climb or bank. On the Sperry, it moved the opposite way.

Imagine you're 21, flying into a pitch-black blizzard at night, and you're exhausted. You look at your instruments. You think you're climbing, but the gauge is actually telling you that you're diving. You pull back, or you push forward, trying to correct a mistake you aren't actually making, and suddenly you're hitting the ground at 170 miles per hour.

They weren't in the air for more than five minutes. The plane didn't explode in the sky. It didn't have engine failure. It simply flew right into the earth at a steep downward angle.

The Aftermath in the Snow

The wreckage wasn't found until the next morning. Jerry Dwyer, worried when the plane never checked in at Fargo, flew the route himself and spotted the silver debris against the white snow.

🔗 Read more: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

It was gruesome.

The plane had tumbled for hundreds of feet. Buddy Holly and Ritchie Valens were found ejected from the fuselage. The Big Bopper had been thrown even further, into a neighboring cornfield. Roger Peterson was the only one still inside the crumpled metal.

Because of the impact, there was no chance of survival. None. The "Day the Music Died" wasn't just a metaphor; it was a violent, physical end to three of the most promising careers in rock and roll history.

Why the Buddy Holly Plane Crash Still Matters

You might wonder why we still talk about this nearly 70 years later. It’s because Buddy Holly was the blueprint. He wrote his own songs. He experimented with double-tracking in the studio. He used the Fender Stratocaster in a way that made every kid in England—including John Lennon and Keith Richards—want to pick up a guitar.

Without Buddy, the Beatles might not have existed in the way we know them. They literally named themselves "The Beatles" as a tribute to Holly’s band, The Crickets.

Debunking the Myths

Over the years, conspiracy theories have bubbled up. People claimed a gun was fired on board because a pistol belonging to Buddy was found at the crash site months later. Some suggested the Big Bopper survived the initial impact and tried to crawl for help.

The 2007 exhumation of J.P. Richardson's body put those rumors to bed. Dr. Bill Bass, a renowned forensic anthropologist, examined the remains and confirmed that the Bopper died instantly from massive fractures. There was no foul play. There was no "struggle for life" in the snow. It was just a tragic, high-speed accident caused by weather and a lack of instrument training.

💡 You might also like: The Entire History of You: What Most People Get Wrong About the Grain

What You Should Do Next

If you really want to understand the weight of this event beyond the headlines, there are a few specific things you can do to see the full picture.

First, go listen to the "undubbed" versions of Buddy Holly's final recordings, often called the Apartment Tapes. He recorded them on a simple tape recorder in his New York City apartment just weeks before he died. You can hear the raw genius—just a man and his guitar. It makes the loss feel much more personal.

Second, if you're ever in the Midwest, visit the Surf Ballroom in Clear Lake, Iowa. It’s one of the few historic venues that hasn't been torn down or turned into a Starbucks. The green room is still covered in signatures from musicians who have passed through over the decades. Walking from that ballroom to the crash site (which is marked by a giant set of steel Wayfarer glasses) gives you a sense of the scale of that night.

Finally, look into the "Winter Dance Party" tour of today. Every year, fans gather to keep the memory alive, not as a funeral, but as a celebration. The best way to honor those who died in the Buddy Holly plane crash is to actually engage with the art they left behind. Don't just read the autopsy reports; listen to Peggy Sue and Donna. That’s where they still live.

The investigation into the crash led to stricter regulations for young pilots and better weather reporting for small airfields. It was a hard-learned lesson that likely saved hundreds of lives in the decades that followed. It’s a small consolation for the loss of a 22-year-old visionary, a 17-year-old prodigy, and a 28-year-old radio giant, but it’s the legacy we’re left with.

Study the FAA reports if you want the cold facts, but listen to the music if you want the truth.

Next Steps for Further Research:

- Examine the CAB Accident Investigation Report (File 2-0001): This is the definitive federal document detailing the weather conditions and pilot errors.

- Read "The Day the Music Died" by Larry Lehmer: This book is widely considered the most factually dense account of the tour and the crash aftermath.

- Explore the Buddy Holly Center Digital Archives: Based in Lubbock, Texas, this resource provides context on his songwriting process and the equipment used during his final sessions.