Imagine driving a car across the Pacific Ocean. Actually, don't imagine it, because that’s exactly what the organizers of the 1908 New York to Paris car race thought would happen. They figured the Bering Strait would just... freeze solid enough to support a two-ton Thomas Flyer. Spoiler alert: it didn't.

This wasn’t just a race. It was a 22,000-mile exercise in pure, unadulterated madness.

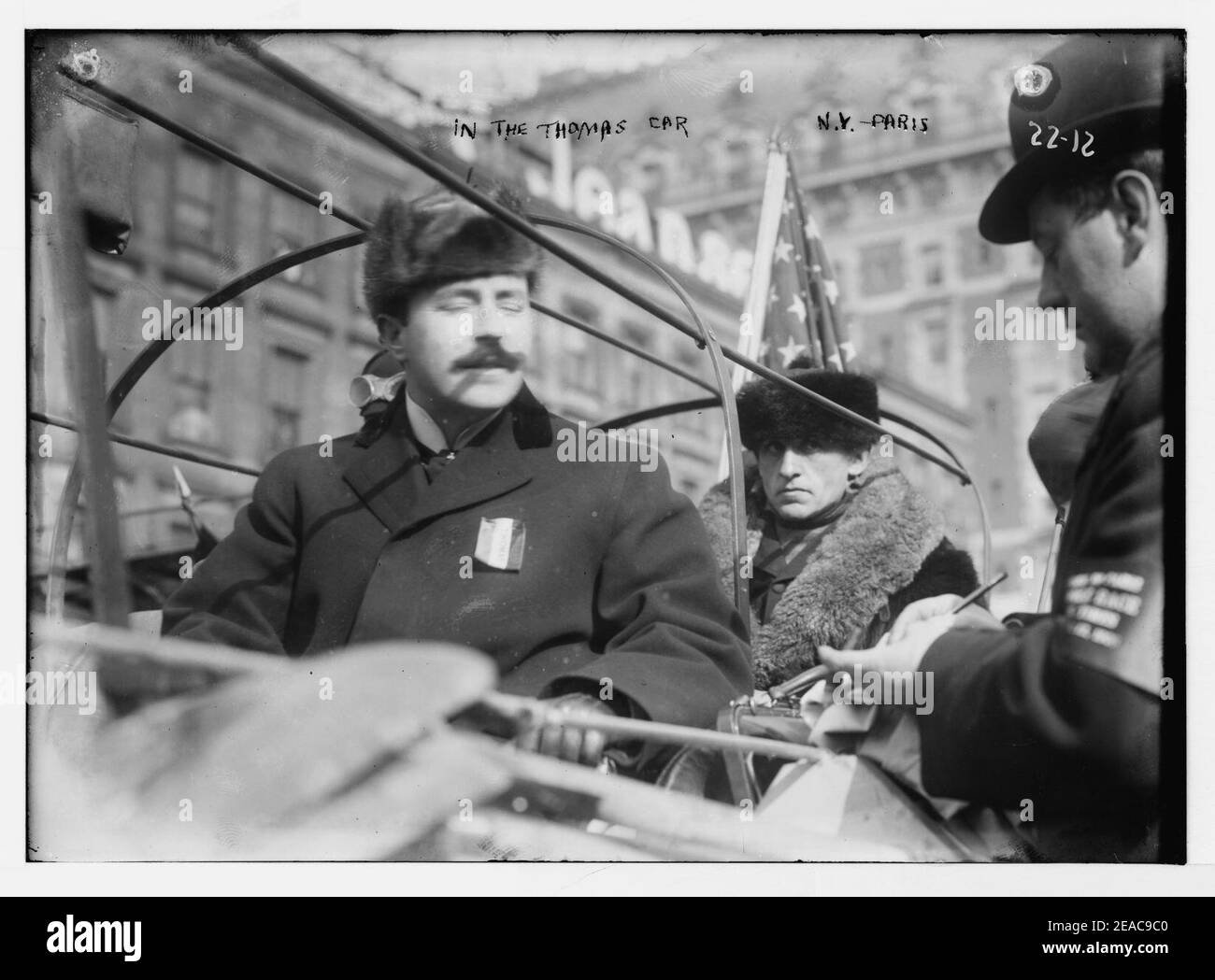

When the starting gun fired in Times Square on February 12, 1908, 250,000 people showed up to watch. That’s a massive crowd even by today's standards, but back then, cars were still basically "horseless carriages" that broke down if you looked at them funny. Six cars started. Only three finished. And the "road" they traveled? Most of the time, it didn't exist.

Why the New York to Paris Car Race was basically a survival horror movie

You’ve got to understand the tech here. We're talking about wood-spoke wheels, literal kerosene lamps for headlights, and engines that produced about as much horsepower as a modern lawnmower. The contestants weren't just racing each other; they were racing against starvation, wolves, and the fact that gasoline had to be pre-positioned by horse-drawn sleds months in advance.

George Schuster, the American driver of the Thomas Flyer, ended up being the MVP of this whole ordeal. While the French and Italian teams were busy dealing with their own mechanical nightmares, Schuster was literally driving his car along railroad tracks through the American West because the mud was too deep to navigate. He had to pull the car off the tracks every time a train came whistling around the bend. Talk about stress.

The Bering Strait blunder and the Alaskan detour

The original plan was for the cars to drive up through Canada and Alaska, cross the ice into Siberia, and then cruise into Europe.

It was a disaster.

📖 Related: London to Canterbury Train: What Most People Get Wrong About the Trip

The American team actually made it to Valdez, Alaska, by ship—only to find out that the snow was ten feet deep and there were no trails. Not "bad roads." No trails. At all. They had to turn around, ship the car back to Seattle, and then cross the Pacific by boat to Japan and eventually Vladivostok.

Honestly, the logistics of the New York to Paris car race make modern rally racing look like a Sunday drive to the grocery store.

The cars that actually tried to do the impossible

It wasn’t just Americans in the mix. The lineup was an international buffet of engineering:

- The Thomas Flyer (USA): A 60-horsepower beast that eventually won.

- The Protos (Germany): Driven by the German Army's Oberleutnant Hans Koeppen. It was a heavy, military-style rig.

- The Züst (Italy): A surprisingly hardy machine that actually finished the race months after the winner.

- The De Dion-Bouton, Motobloc, and Sizaire-Naudin (France): All three eventually dropped out, though the De Dion made it quite a ways before the team threw in the towel in Siberia.

The German Protos actually arrived in Paris first. But there was a catch—a big one. Because Koeppen had loaded his car onto a train for a huge chunk of the American leg to save time, he was penalized 30 days.

Schuster and the Thomas Flyer arrived four days later, but because they had actually driven the Alaskan detour (or tried to), they were credited with the win. The math was messy, the politics were worse, but the American car took the trophy.

Siberia: Where the race almost ended in tragedy

If you think the American mud was bad, Siberia was another level.

👉 See also: Things to do in Hanover PA: Why This Snack Capital is More Than Just Pretzels

Once the teams landed in Vladivostok, they faced the "Rasputitsa"—the season of quagmire. The mud was so thick it would swallow wheels whole. There were reports of the Italian team being stalked by packs of wolves. Schuster himself wrote about the sheer physical exhaustion of digging a multi-ton car out of Siberian muck for 18 hours a day.

There was no GPS. No cell service. No AAA. If your axle snapped in the middle of the Steppe, you were basically a pioneer again. You had to find a local blacksmith who had never seen a car before and convince him to forge a part based on a drawing in the dirt.

The legacy of the 1908 New York to Paris car race

People often ask: Why does this matter now?

Because this race proved the car was a viable means of long-distance transport. Before 1908, the automobile was a toy for the rich to drive around city parks. After Schuster pulled into Paris on July 30, 1908—covered in dust and looking like he’d been through a war—the world realized that roads needed to be built.

It birthed the modern road trip.

It also solidified the reputation of American manufacturing at a time when European cars were considered the gold standard. The Thomas Flyer became a legend. It’s currently sitting in the National Automobile Museum in Reno, Nevada. If you ever see it in person, you’ll notice it looks surprisingly small for something that conquered the world.

✨ Don't miss: Hotels Near University of Texas Arlington: What Most People Get Wrong

What most people get wrong about the finish line

A common misconception is that the race ended in a glorious sprint down the Champs-Élysées.

In reality, when Schuster arrived in Paris, he was stopped by a gendarme because his car had a broken headlight. The policeman didn't care that he’d just driven from New York. No light meant no entry. Schuster supposedly had to find a bicycle, strap it to the front of the car, and use its lamp to legally drive to the finish.

That’s the kind of absurdity that defined the whole event.

How to explore this history today

If you're a fan of the New York to Paris car race, you don't have to just read about it. There are actual ways to engage with this insanity.

- Visit the Thomas Flyer: Go to the National Automobile Museum in Reno. Seeing the actual metal and wood that survived Siberia is a religious experience for gearheads.

- Read the primary source: Get a copy of The Longest Race by George Schuster. It’s his first-hand account. It’s gritty, it’s honest, and it’s way better than any fictionalized version.

- Trace the route: While you can't drive the exact 1908 path (geopolitics and lack of ice bridges make it tough), you can drive the Lincoln Highway in the US, which covers much of the original American leg.

- Watch "The Great Race" (1965): It’s a comedy loosely—very loosely—inspired by the 1908 event. It’s not a documentary, but it captures the "anything goes" spirit of early motoring.

The 1908 race was the last of its kind. We’ll never see anything like it again because the world is too mapped, too paved, and too connected. But for 169 days, the world watched a handful of men do something that was, by all logical accounts, impossible. They didn't just drive to Paris; they dragged the 20th century along with them.

For those looking to understand the sheer scale of the achievement, look at the numbers: 169 days of travel, 22,000 miles covered, and a winning margin that came down to a 30-day penalty. It remains the longest motorized competition in history. If you're planning a road trip this summer and find yourself complaining about a two-hour delay or a lack of snacks, just remember George Schuster. He didn't have a heater, he didn't have a windshield, and he had to worry about wolves. You'll be fine.