Imagine walking into a clothing store in 1870, handing over twenty-five cents, and being ushered into a subterranean world that felt more like a Victorian parlor than a transit hub. This wasn't some steampunk fantasy. It was real. Alfred Ely Beach, the brilliant mind behind Scientific American, built a functioning New York pneumatic subway right under the noses of corrupt politicians.

He had to.

Boss Tweed—the infamous king of Tammany Hall—controlled the city's transit permits. He wanted overhead trains because they were cheaper to build and offered more opportunities for graft. Beach knew his vision for an underground, air-powered railway would never get past Tweed's desk. So, he lied. He applied for a permit to build a pneumatic mail tube system. In reality, he dug a tunnel large enough to fit a luxury passenger car. It was the ultimate "fake it till you make it" move in engineering history.

Why the New York pneumatic subway was a technical marvel

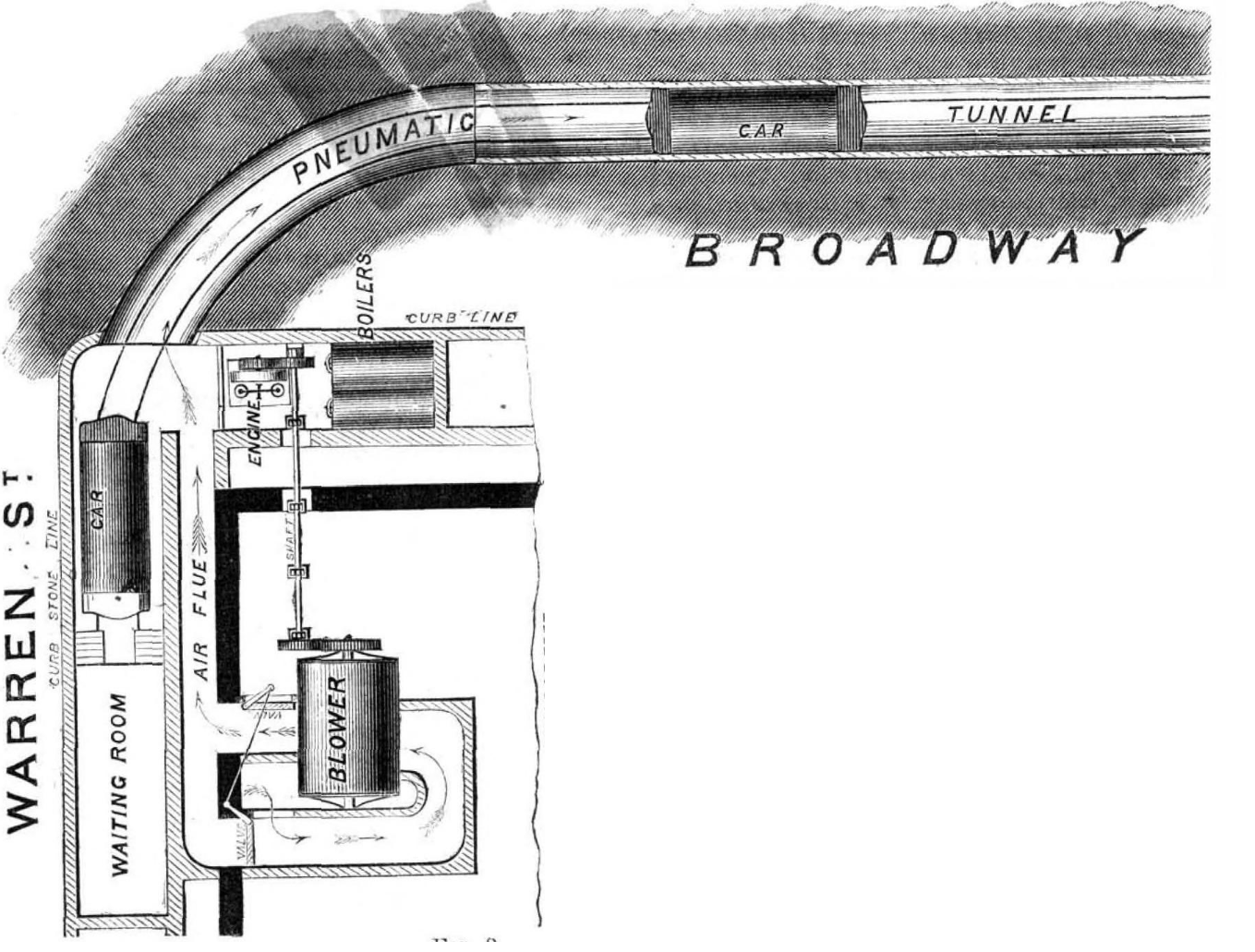

The mechanics were surprisingly simple but effective. Instead of a locomotive pulling a train, Beach used a massive 48-ton fan called "The Western Tornado." When the fan blew, it pushed the cylindrical car forward. When it reversed, it sucked the car back. Physics, honestly, is pretty cool when you apply it to a 175-foot-long tunnel.

The car itself was a far cry from the grime-streaked metal boxes we ride today. It sat 22 people. It had plush velvet seats, zircon lamps for lighting, and actual paintings on the walls. Beach didn't just want to move people; he wanted to impress them. He needed to prove that being underground wasn't a death sentence of soot and smoke.

✨ Don't miss: When were iPhones invented and why the answer is actually complicated

Construction was an ordeal. Beach's team used a hydraulic tunneling shield, which he actually invented himself, to push through the dirt under Broadway without disturbing the surface. They worked at night. They hauled dirt out in bags to avoid suspicion. When it finally opened in February 1870, it was an overnight sensation. Thousands of people lined up to pay a quarter for a ride that went... nowhere.

Well, it went one block. From Warren Street to Murray Street.

It was a proof of concept. A high-stakes demo. Beach hoped the public's excitement would force the state legislature to grant him a permit to extend the line all the way to Central Park. People loved it. In its first year, the New York pneumatic subway carried over 400,000 passengers. They marveled at the goldfish pond in the waiting room and the frescoed walls. It felt like the future had arrived a century early.

The political wall that killed the dream

Engineering is often the easy part. Politics? That's where things get messy. Even though Beach eventually secured a permit to expand after Boss Tweed was ousted, the timing couldn't have been worse. The Panic of 1873 hit. Investors disappeared. The economy tanked. The money for a full-scale New York pneumatic subway simply dried up.

🔗 Read more: Why Everyone Is Talking About the Gun Switch 3D Print and Why It Matters Now

Beach's tunnel was sealed.

It sat there, forgotten, for decades. When workers were digging the BMT Broadway Line in 1912, they broke into a hollow space and found something eerie. There was the tunnel. There was the car, its velvet upholstery rotting away but still recognizable. There was the piano from the waiting room. It was a time capsule of a future that never quite happened. Today, the City Hall station on the R line sits near where that original experiment lived, though almost nothing remains of Beach's specific work.

What most people get wrong about pneumatic transit

You’ll often hear people say that pneumatic power was "inefficient" and that’s why it failed. That's a bit of a simplification. While it's true that scaling a giant fan to power miles of track would have been a massive energy hog compared to later electric motors, Beach’s real obstacle wasn’t the air pressure. It was the lack of capital and the sheer density of Manhattan’s bedrock.

Others think this was just a "mail tube" that someone happened to ride. Nope. Beach always intended for people to be the cargo. The mail tube cover story was strictly to bypass the corrupt bureaucracy of the 1860s. He was a visionary who understood that if you want to solve New York’s congestion, you have to go down.

💡 You might also like: How to Log Off Gmail: The Simple Fixes for Your Privacy Panic

Why the tech still matters today

Interestingly, we see echoes of the New York pneumatic subway in modern concepts like the Hyperloop. While the Hyperloop uses a vacuum and magnetic levitation, the core idea—moving a pod through a tube using pressure differentials—is basically Beach's "Western Tornado" on steroids.

The legacy of the project isn't just the tech, though. It’s the audacity. Beach showed that you could tunnel under a major city without the buildings falling down. He proved that the public wouldn't be afraid of the "dark" if the environment was pleasant. He basically paved the psychological way for the Interborough Rapid Transit (IRT) system that finally opened in 1904.

Key takeaways for transit history buffs

If you're looking for traces of the New York pneumatic subway today, you're mostly out of luck in terms of physical sites. Most of it was demolished during the construction of the current subway lines. However, you can still find the legacy of Alfred Ely Beach in the archives of the New York Historical Society and the Museum of the City of New York.

- Beach's Shield: The tunneling method used is still the fundamental basis for how we dig tunnels today.

- The Waiting Room: It remains a legendary example of "placemaking" in transit design—treating a station as a destination, not just a transition point.

- The Politics: A reminder that the best technology doesn't always win if the political and economic climate is hostile.

To truly understand the New York pneumatic subway, you have to look at it as a piece of performance art as much as an engineering project. Beach was selling a dream. He was convincing a horse-and-buggy world that they belonged in the 20th century. Even though his tunnel was short, his vision was miles long.

If you want to dive deeper, I recommend looking into the original Scientific American archives from 1870. The illustrations of the "Western Tornado" fan are incredible. You can also visit the Warren Street area in Manhattan; while you won't see the zircon lamps, you'll be standing right above the spot where New York's first subway riders once sat in velvet-lined luxury, marveled at the physics of air, and wondered if they’d ever see a train that reached Central Park.

To further your research on early urban transit, look into the following steps:

- Examine the 1870-1873 New York state legislative records regarding the "Beach Pneumatic Transit Company" to see the specific legal hurdles they faced.

- Search digital archives for the 1912 New York Times reports on the "rediscovery" of the tunnel during BMT construction for firsthand accounts of what was found.

- Compare the pneumatic car's diameter (8 feet) with modern subway clearances to see how Beach's compact design influenced future underground spatial planning.