If you’ve ever sat on a Metro-North train staring out at the Long Island Sound or grabbed an Acela from Boston to DC, you’re basically riding on a ghost. Or, more accurately, you’re riding on the bones of a titan. The New York New Haven and Hartford Railroad, usually just called "The New Haven" by the people who loved it (and the people who hated its delays), wasn't just another company. It was a monopoly so powerful it literally defined the economy of Southern New England for a century.

Railroads today feel like a public service, something we complain about when the overhead wires sag in the heat. But back then? The New Haven was a kingmaker. It was the only game in town. If you wanted to move a brass clock from Waterbury or a crate of oysters from South Norwalk, you paid the New Haven.

It’s a wild story.

We’re talking about a company that at its peak owned almost everything that moved in Connecticut and Rhode Island—trains, trolleys, even steamships. It was the "Consolidated." It was JP Morgan’s personal playground. And then, in a slow-motion car crash that took decades, it fell apart. But honestly, the fact that we still have a functioning rail corridor between New York and Boston is a miracle left behind by the engineers of the New Haven.

The JP Morgan Era and the Monopoly That Almost Broke New England

The New York New Haven and Hartford Railroad didn't start as a behemoth. It was born from the 1872 merger of the New York & New Haven and the Hartford & New Haven. Simple enough. But then JP Morgan stepped in.

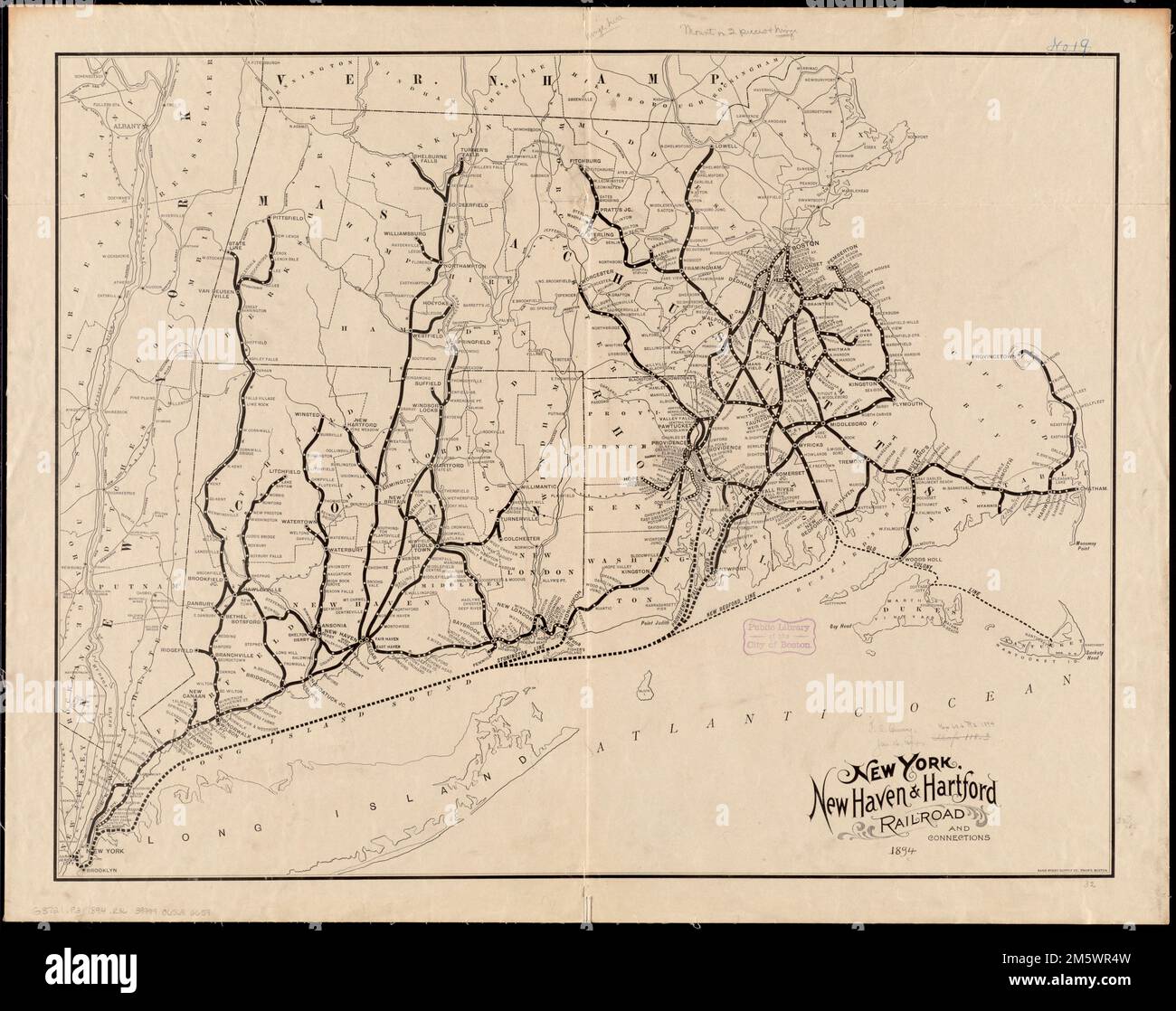

Morgan had a vision that would make a modern antitrust lawyer faint. He wanted "community of interest." Translation: He wanted to own it all. Under the leadership of Charles S. Mellen, Morgan’s hand-picked president, the New Haven went on a shopping spree that was frankly insane. They didn't just buy other railroads. They bought the Connecticut Railway and Lighting Company. They bought the Joy Line and the Fall River Line steamships. By 1912, the New Haven controlled over 2,000 miles of track and basically 80% of all water traffic in the region.

It was a house of cards, though.

They were over-leveraged. The debt was astronomical. While the New Haven was busy buying up competitors to kill competition, they weren't always maintaining the actual tracks. Louis Brandeis—yeah, the future Supreme Court Justice—became the railroad’s public enemy number one. He saw the rot before anyone else did. He wrote Other People’s Money and How the Bankers Use It largely as a takedown of the New Haven’s financial recklessness.

Brandeis proved that the railroad was cookin' the books to hide its losses. It was a massive scandal. In 1913, Mellen resigned under a cloud of federal investigations. The monopoly was forced to start selling off its pieces. But the damage to the balance sheet was done. The New Haven would spend the next fifty years trying to outrun its own debt.

👉 See also: Wall Street Lays an Egg: The Truth About the Most Famous Headline in History

When the New Haven Was Actually Cool: Innovation and Electrification

Despite the corporate drama, the New York New Haven and Hartford Railroad was a technical marvel. If you’re a railfan, this is the part that matters.

They were pioneers.

While other railroads were still choking on coal smoke, the New Haven was electrifying. They had to. New York City passed a law in 1903 banning steam locomotives in Manhattan after a horrific crash in the Park Avenue Tunnel. The New Haven didn't just comply; they went big. They implemented a high-voltage AC electrification system that was decades ahead of its time.

The EP-1, built by Westinghouse and Baldwin, was one of the first truly successful electric locomotives. It could pull heavy trains into Grand Central Terminal without suffocating the passengers. This wasn't just about being "green"—it was about efficiency. You could run more trains, faster.

Then came the legendary locomotives.

- The EP-5 "Jets": These were the chrome-striped beauties of the 1950s. They hummed like jet engines (hence the nickname) and could run on both AC overhead wires and the DC third rail used by the New York Central.

- The FL9: This was the Swiss Army knife of locomotives. It was an EMD diesel-electric that could also pull power from a third rail. It was a genius solution for the "commuter problem," allowing trains to run from non-electrified branch lines directly into the heart of Manhattan.

And we can't talk about the New Haven without talking about Patrick McGinnis and the "New Look."

In the mid-50s, McGinnis and his wife Lucille decided the railroad needed a brand. They hired Herbert Matter, a Swiss graphic designer, to create the "NH" logo. You know the one—the bold, interlocking orange, black, and white letters. It’s a masterpiece of mid-century modern design. Even today, Metro-North uses a version of it on their heritage fleet because it’s just that iconic. They painted the trains in "McGinnis Red" (which was actually a vibrant orange-red) and for a brief moment, the New Haven looked like the future.

The Long Slow Decline into the Penn Central Disaster

Post-WWII was brutal for the New Haven.

✨ Don't miss: 121 GBP to USD: Why Your Bank Is Probably Ripping You Off

The Interstate Highway System was the nail in the coffin. Why take a train from Hartford to New York when you could drive your new Cadillac on the turnpike? Freight business, which was the lifeblood of the railroad, started migrating to trucks. The New Haven’s geography worked against it, too. It was a "terminal" railroad. It didn't have long hauls like the Union Pacific. Most of its trips were short, which meant high overhead and low margins.

By the 1960s, the New York New Haven and Hartford Railroad was a "ward of the court." It went bankrupt in 1961.

It limped along for years. The equipment got shabby. The tracks got "slow orders" because they were too dangerous to ride at high speeds. The federal government eventually stepped in and forced a shotgun wedding. They told the Pennsylvania Railroad and the New York Central that if they wanted to merge into the Penn Central, they had to take the dying New Haven with them.

It was a disaster.

The Penn Central merger in 1968 was the Titanic hitting the iceberg. The New Haven was the anchor that helped drag it down. By 1970, Penn Central was bankrupt—the largest corporate failure in American history at that point.

Why the New Haven Legacy Actually Matters in 2026

So why are we still talking about a railroad that technically died in 1969?

Because without the New York New Haven and Hartford Railroad, the Northeast Corridor (NEC) wouldn't exist. Amtrak’s busiest and most profitable route—the line from New York to Boston—is the old New Haven mainline.

The state of Connecticut eventually took over the commuter operations, which became the Metro-North New Haven Line. Every time you see a train stop at Stamford or New Haven State Street, you're seeing the New Haven’s ghost in action. The infrastructure they built, from the Hell Gate Bridge to the massive catenary structures that still stand in Fairfield County, is the backbone of the region’s economy.

🔗 Read more: Yangshan Deep Water Port: The Engineering Gamble That Keeps Global Shipping From Collapsing

There's also the "Shore Line" through Rhode Island. It’s some of the most beautiful railroading in the country. The New Haven fought for those rights-of-way for decades, and today, they are the only reason you can get from Providence to Penn Station in under three hours.

Surprising Facts Most People Get Wrong

- It wasn't just a railroad. The New Haven owned a massive fleet of steamships. For a long time, the "Fall River Line" was the most luxurious way to get from New York to Boston. You'd take a train to Fall River, Massachusetts, and then hop a floating palace to Manhattan.

- They tried "High Speed Rail" in the 60s. Long before the Acela, the New Haven experimented with the United Aircraft TurboTrain. It was a sleek, gas-turbine-powered train that looked like a spaceship. It reached 170 mph in testing, but the old New Haven tracks were too rickety to handle it in regular service.

- The "Commuter" was born here. The New Haven was one of the first railroads to realize that moving people from the suburbs to the city was a distinct business model. They built the massive parking lots and station houses that shaped towns like Greenwich and Darien.

How to Experience the New Haven Today

You can't buy a ticket on the New York New Haven and Hartford Railroad anymore, but you can find the pieces of it if you know where to look.

If you're in Connecticut, visit the Danbury Railway Museum. It’s located in the old New Haven railyards and houses an incredible collection of original equipment, including those FL9 locomotives.

The Valley Railroad in Essex, Connecticut, is another gem. They operate steam trains on an old New Haven branch line. It’s the closest you’ll get to feeling what the railroad was like in its prime before the "McGinnis Red" and the stainless steel took over.

Walk the Air Line State Park Trail. This was once the New Haven’s "Air Line" route—a bold attempt to build a perfectly straight, flat line from New York to Boston by bridging massive ravines. It was a feat of engineering that eventually failed because the iron bridges couldn't handle the weight of modern locomotives, but today, it’s a stunning rail-trail for hikers and bikers.

Moving Forward: Actionable Insights for History and Transit Buffs

If you're interested in the New Haven, don't just read the Wikipedia page. Dive into the primary sources.

- Check out the New Haven Railroad Historical and Technical Association (NHRHTA). They publish Shoreliner magazine, which is the gold standard for accurate info on the company.

- Study the architecture. Look at the stations in New Haven (Union Station) and Hartford. These weren't just transit hubs; they were cathedrals of commerce designed to show off the railroad’s power.

- Ride the Shore Line East or Metro-North. Pay attention to the catenary (the overhead wires). Much of the hardware you see is either original or follows the exact engineering specs laid out by the New Haven’s electrical engineers over a century ago.

The story of the New York New Haven and Hartford Railroad is a cautionary tale about corporate greed and a tribute to American engineering. It’s a reminder that even when a company dies, the things it built can continue to serve millions of people every single day. The "Consolidated" might be gone, but the tracks still hum.

To truly understand the New Haven’s impact, your best bet is to visit the Connecticut State Library in Hartford, which holds a massive archive of the railroad’s records, including original maps and corporate correspondence that reveal the true scale of JP Morgan's ambitions. Additionally, exploring the Railroad Museum of New England in Thomaston offers a hands-on look at the vintage rolling stock that survived the Penn Central merger. Understanding this history isn't just about nostalgia; it’s about recognizing how past infrastructure decisions still dictate the speed and efficiency of our modern lives.