It wasn't a subway. It wasn't a Hyperloop. Honestly, it wasn't even a tunnel in the way most people think of one, but for a few wild weeks in 2008, the New York and London tunnel—officially known as the Telectroscope—was the only thing anyone wanted to talk about.

Imagine standing at the base of the Brooklyn Bridge. You look into a massive, brass-and-wood Victorian eyepiece that looks like something straight out of a Jules Verne novel. You wave. Suddenly, a guy standing near Tower Bridge in London waves back in real-time. This wasn't some grainy Zoom call on a cracked iPhone 3G. It felt like peering through a hole in the earth. People were freaking out. They were holding up signs to propose marriage, showing off newborn babies, and playing rock-paper-scissors across the Atlantic Ocean.

The Telectroscope was a massive art installation by Paul St George. It leaned heavily into a "found history" narrative that suggested his great-grandfather had actually started digging a trans-Atlantic tunnel a century prior.

The Tech Behind the Magic

Most people actually believed there was a physical hole under the ocean. They didn't.

The "tunnel" was actually a very clever use of 2008-era fiber optic technology. While the world was still getting used to the idea of high-speed internet, St George utilized a dedicated broadband link to transmit high-definition video between the two cities. The magic wasn't in the digging; it was in the presentation. The Victorian aesthetic of the Telectroscope—huge brass plates, giant bolts, and that sepia-toned steampunk vibe—tricked the brain into ignoring the digital reality.

It used two identical "scopes." One sat at Fulton Ferry Landing in Brooklyn, and the other lived at City Hall Plaza in London.

Why the Illusion Worked So Well

We live in a world of screens now, but in 2008, a life-sized, 24/7 video portal felt impossible. The New York and London tunnel worked because it played on a very human desire for connection.

There's this specific psychological effect where, if you make the "window" big enough, your brain stops seeing a screen and starts seeing a space. St George understood this perfectly. By branding it as a "Telectroscope," he tapped into the 19th-century obsession with "electro-scopes" and early television concepts. It felt historical. It felt heavy. It didn't feel like a computer.

👉 See also: LG UltraGear OLED 27GX700A: The 480Hz Speed King That Actually Makes Sense

The Viral Moment Before "Viral" Was a Thing

Long before TikTok trends, this project went absolutely nuclear in the press.

The New York Times and the BBC were obsessed. Thousands of people lined up for hours just to spend a few minutes staring into the brass abyss. It was one of the first times we saw a physical "phygital" (physical plus digital) installation capture the global imagination. It wasn't just an art piece; it was a proof of concept for how we would eventually live—constantly connected to people thousands of miles away.

But there’s a catch.

Keeping a dedicated, high-bandwidth fiber optic line open between two continents 24/7 isn't cheap. The logistics involved in the New York and London tunnel were a nightmare of city permits and technical redundancy. When the installation ended, the "tunnel" vanished. The brass was packed up. The screens went dark.

The Real Trans-Atlantic Tunnels (That Aren't Art)

If we're being real, a physical tunnel for trains or cars between NYC and London is basically impossible with current physics.

The distance is roughly 3,400 miles. For context, the Channel Tunnel (Chunnel) connecting the UK and France is only 31 miles. To build a real New York and London tunnel, you'd have to deal with the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, depths of over 12,000 feet, and tectonic plates that are literally pulling away from each other.

The pressure at the bottom of the Atlantic is enough to crush almost any structure we can currently build for transport.

✨ Don't miss: How to Remove Yourself From Group Text Messages Without Looking Like a Jerk

- Distance: 3,459 miles (approximate).

- Deepest Point: The Puerto Rico Trench is over 27,000 feet, though a direct line would hit depths around 12,000-15,000 feet.

- The Mid-Atlantic Ridge: A massive underwater mountain range that is volcanically active.

Basically, unless we figure out how to build a vacuum tube that can withstand thousands of pounds of pressure per square inch while floating in the abyssal zone, the Telectroscope is the closest we’re ever going to get.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Project

The biggest misconception? That it was a hoax.

It wasn't a hoax. It was art. St George never claimed he actually dug a hole; he claimed his fictional ancestor did. It was a piece of "steampunk" performance art that used real-time cameras. People who felt "tricked" were usually the ones who didn't read the artist's statement.

But even if it was "just a webcam," the impact was real. It proved that distance is a psychological barrier, not just a physical one. When you can see the eyelashes of someone in London while you're standing in Brooklyn, the ocean feels like a puddle.

The Legacy of the Telectroscope

You can see the DNA of the New York and London tunnel in projects like the "Portal" installations that popped up in Dublin and NYC recently. Those modern versions are basically the Telectroscope without the brass and the cool backstory.

The 2008 project was arguably better because it had a soul. It wasn't just a flat screen on a sidewalk; it was an invitation to believe in a world where Victorian engineers were smarter than us. It challenged the "newness" of the internet by dressing it up in the past.

Technical Hurdles of a Physical Tunnel

Let's say some billionaire actually tried to build a real one.

🔗 Read more: How to Make Your Own iPhone Emoji Without Losing Your Mind

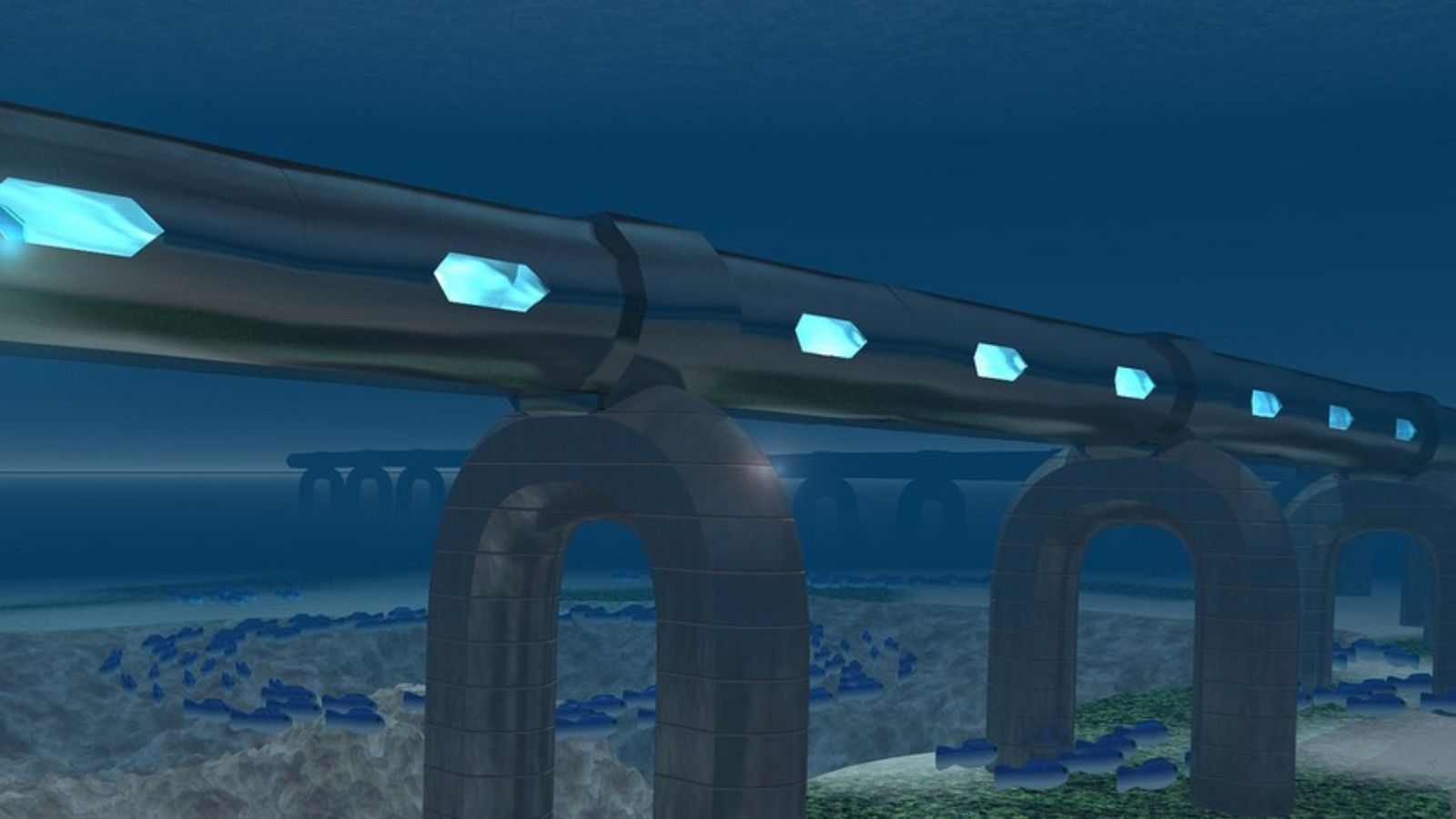

You'd need a "submerged floating tunnel." This is a real concept where the tunnel isn't on the seabed but floats about 100 feet below the surface, tethered to the floor. Norway is actually looking into this for their fjords. But across the Atlantic? The currents would rip it apart. The sheer amount of material needed would deplete global steel supplies.

And then there's the speed.

Even if you had a maglev train going 500 mph in a vacuum (a Hyperloop), it would still take almost seven hours to get from NYC to London. That's the same time as a flight, but with a trillion-dollar price tag. It just doesn't make sense.

How to Experience the "Tunnel" Vibe Today

While the Telectroscope is long gone, the spirit of the New York and London tunnel lives on through high-definition telepresence.

If you want to recreate that feeling of "connectedness," look into the following:

- The Dublin-NYC Portals: These are the spiritual successors to the Telectroscope, though they often get shut down due to people behaving badly on camera.

- Steampunk Festivals: Often feature tributes to Paul St George’s work and the aesthetic of "impossible Victorian engineering."

- WindowSwap: An amazing website where you can look out of someone else’s window anywhere in the world. It’s the low-tech, cozy version of the Atlantic tunnel.

The New York and London tunnel remains a landmark moment in the history of public art. It showed us that we don't need to move our bodies across the world to feel like we're somewhere else. Sometimes, all we need is a very long piece of glass and a bit of imagination.

Next Steps for Enthusiasts:

- Research Paul St George: Look into his other "Telectroscope" drawings to see the full fictional history he mapped out.

- Study the "Chunnel" Logistics: If you're interested in real engineering, compare the costs of the 31-mile UK-France tunnel to see why a trans-Atlantic version is currently a fantasy.

- Visit the Locations: Stand at Fulton Ferry Landing in Brooklyn or City Hall Plaza in London. Even without the brass scope, you can feel the scale of the connection the project tried to bridge.