You’ve probably seen the memes of Sean Connery in a brown cowl, looking suspiciously like a medieval James Bond. That’s basically the vibe of The Name of the Rose 1986, a movie that somehow managed to turn a dense, 500-page Italian semiotics novel into a muddy, gross, and surprisingly gripping Sherlock Holmes story.

It shouldn't have worked. Honestly, Umberto Eco’s book is famously difficult—it’s packed with Latin, theological debates about whether Jesus owned his own clothes, and long rants about the apocalypse. Yet, director Jean-Jacques Annaud looked at all that and decided it would make a great mainstream thriller. He was right.

Why the setting of The Name of the Rose 1986 feels so real

Most medieval movies look like they were filmed in a sanitized Renaissance Fair. Not this one. The Name of the Rose 1986 is obsessed with dirt. You can almost smell the rot coming off the screen.

The production design team spent a fortune building a massive monastery on a hilltop outside Rome. They didn't just build a set; they built a world. Dante Ferretti, the legendary production designer, crafted a labyrinthine library that feels genuinely claustrophobic. It’s dark. It’s cold.

Characters have bad teeth. Their skin is sallow. When you watch Sean Connery as William of Baskerville, he’s not just a hero; he’s a guy trying to solve a murder while surrounded by people who haven't bathed in a year. This "palpable filth" is what gives the film its staying power. It feels lived-in.

The movie deals with a series of bizarre deaths in a Benedictine abbey. Monks are turning up dead in vats of pig blood or slumped over desks with black stains on their fingers. While the local monks think the Devil is doing his dirty work, William thinks there’s a logical explanation. It’s a classic clash between the Enlightenment and the Dark Ages, even if the Enlightenment hadn't technically happened yet.

Sean Connery and the casting gamble

Here is a fun fact: Umberto Eco was initially horrified at the thought of Sean Connery playing William of Baskerville. At the time, Connery’s career was in a bit of a slump. He was "the guy who used to be Bond."

Annaud had to fight for him. He auditioned tons of actors, but Connery had this specific intellectual weight combined with physical presence. He plays William with a dry, weary wit. You believe he’s the smartest guy in the room, even when that room is filled with religious fanatics who want to burn him at the stake.

💡 You might also like: Why This Is How We Roll FGL Is Still The Song That Defines Modern Country

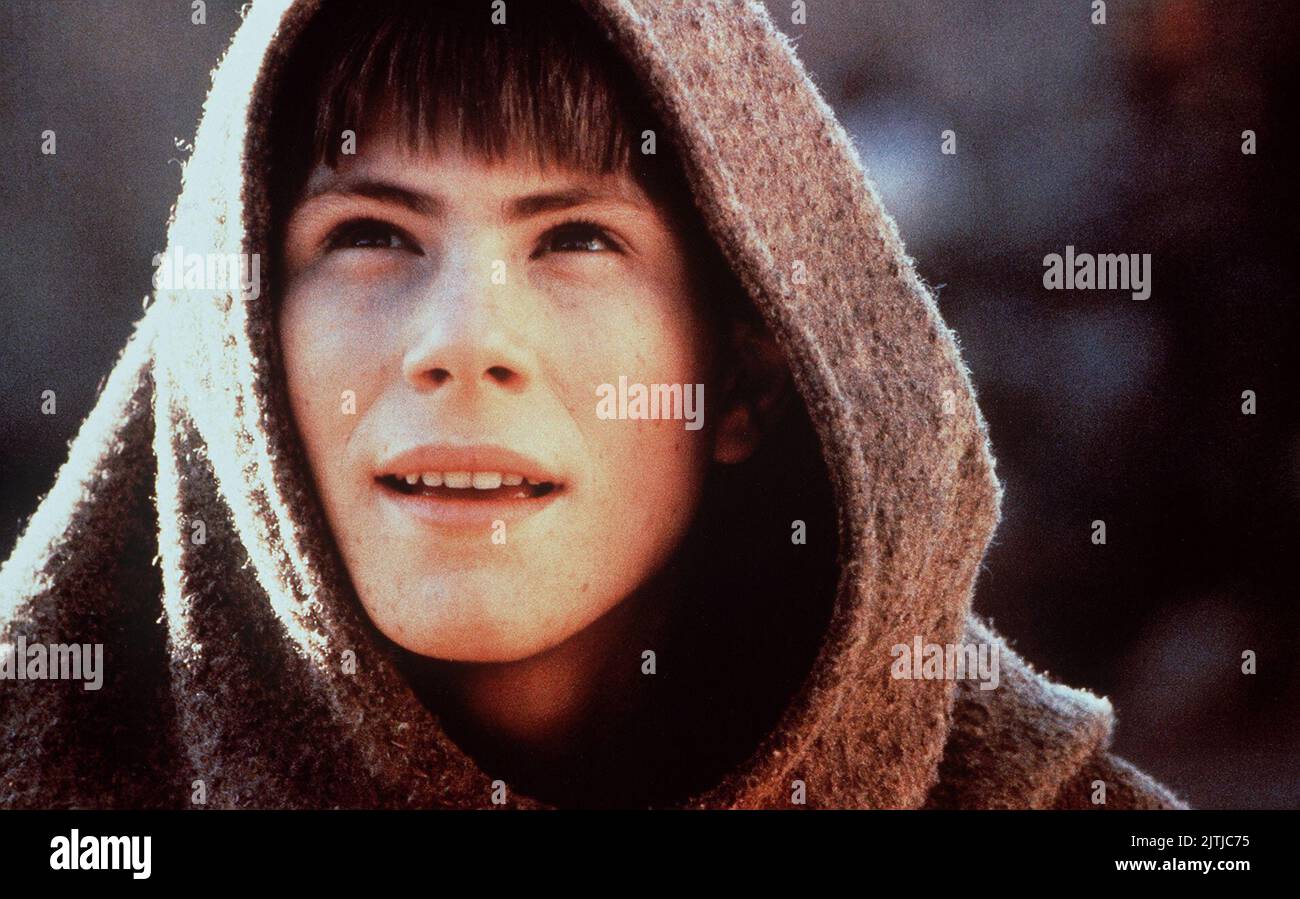

Then you have a very young Christian Slater as Adso of Melk. It was one of his first big roles. He’s the audience surrogate, the naive novice who is basically there to say, "Master, what does this mean?" and look terrified. Their chemistry works because it feels like a genuine mentorship.

But the real MVP of the cast might be F. Murray Abraham as Bernardo Gui. Fresh off his Oscar win for Amadeus, Abraham plays the Inquisitor with a chilling, quiet menace. He doesn't scream. He just leans in and explains why he’s going to torture you. It’s terrifying.

The controversy over the library

In the film, the library is a literal maze—a "Great Aedificium" with stairs that go nowhere and secret doors. This is where the movie leans into its Gothic horror roots.

The mystery revolves around a "lost" book by Aristotle. Specifically, the second book of his Poetics, which was supposed to be about comedy. In the world of The Name of the Rose 1986, laughter is seen as a threat to faith. If people laugh, they don't fear God. If they don't fear God, the Church loses its power.

It’s a heavy concept for a popcorn flick.

While the movie simplifies the book’s complex philosophical arguments, it keeps the core idea: knowledge is dangerous. The villain isn't a demon; it's a man who wants to keep people in the dark.

Is it actually historically accurate?

Sorta.

📖 Related: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

The movie gets a lot of the "vibe" right. The internal politics of the Church—the split between the Franciscans (who wanted the Church to be poor) and the Papacy in Avignon (who definitely did not)—is historically grounded. These were real life-or-death arguments in the 14th century.

However, the "Aedificium" library is a total invention. Real medieval libraries were usually just rooms with chests or shelves, not M.C. Escher nightmares. And the Inquisition, while brutal, didn't always operate with the cartoonish villainy seen in the climax of the film.

But who cares? It’s a movie.

The cinematography by Tonino Delli Colli uses natural light—or at least the appearance of it—making every scene look like a Rembrandt painting. The contrast between the flickering orange of the candles and the deep, oppressive blue of the night creates a visual tension that modern CGI-heavy movies just can't replicate.

Why people are still watching it in 2026

We live in an era of information overload. The Name of the Rose 1986 is about the opposite: the gatekeeping of information.

In a world where we’re constantly arguing about "fake news" and who gets to control the narrative, a story about a monk killing people to hide a book feels weirdly relevant. It’s a reminder that whoever controls the books (or the servers) controls the reality of everyone else.

Plus, it’s just a great detective story.

👉 See also: Love Island UK Who Is Still Together: The Reality of Romance After the Villa

If you strip away the monk robes and the Latin, you have a classic "locked room" mystery. William uses logic, observation, and what we would now call forensic science to solve the case. He looks at footprints. He examines the chemical properties of ink. He’s a modern man trapped in a world that refuses to move forward.

The film was a massive hit in Europe, though it struggled a bit in the US initially. Over time, it’s become a cult classic. It’s one of those movies you find on a rainy Sunday afternoon and end up watching the whole way through because the atmosphere is just so thick.

Key details you might have missed

- The movie was filmed at the Eberbach Abbey in Germany for many interior shots.

- The script went through about 15 different versions.

- Ron Perlman (of Hellboy fame) plays Salvatore, a hunchbacked monk who speaks a jumbled mess of five different languages. He’s unrecognizable and brilliant.

- The score by James Horner is haunting, using synthesizers mixed with choral arrangements to create an eerie, anachronistic feel.

The film doesn't have a happy ending in the traditional sense. It’s bittersweet. William solves the crime, but the knowledge he tried to save is lost. The monastery burns. The library, with all its "dangerous" secrets, turns to ash.

It’s a reminder that logic can solve a murder, but it can’t always save the world from human stupidity or fanaticism.

How to experience the story today

If you want to get the most out of The Name of the Rose 1986, don't just watch it on a tiny phone screen. This is a movie that demands a dark room and a big display.

- Watch the 1986 film first. It’s the most accessible entry point and perfectly captures the Gothic aesthetic.

- Compare it to the 2019 miniseries. If you want more of the theological meat from the book, the John Turturro series is much more faithful to the source material, though it lacks the grittiness of the '86 version.

- Read the book (if you’re brave). It’s a tough read, but it explains why the monks were so obsessed with those specific religious arguments.

- Look for the 4K restorations. Recent transfers have cleaned up the grain while preserving the "muddy" look, making the details in the library scenes pop.

This film remains the gold standard for medieval mysteries. It’s smart, it’s gross, and it respects the intelligence of the audience. In a sea of generic historical dramas, it stands alone as a weird, beautiful anomaly.