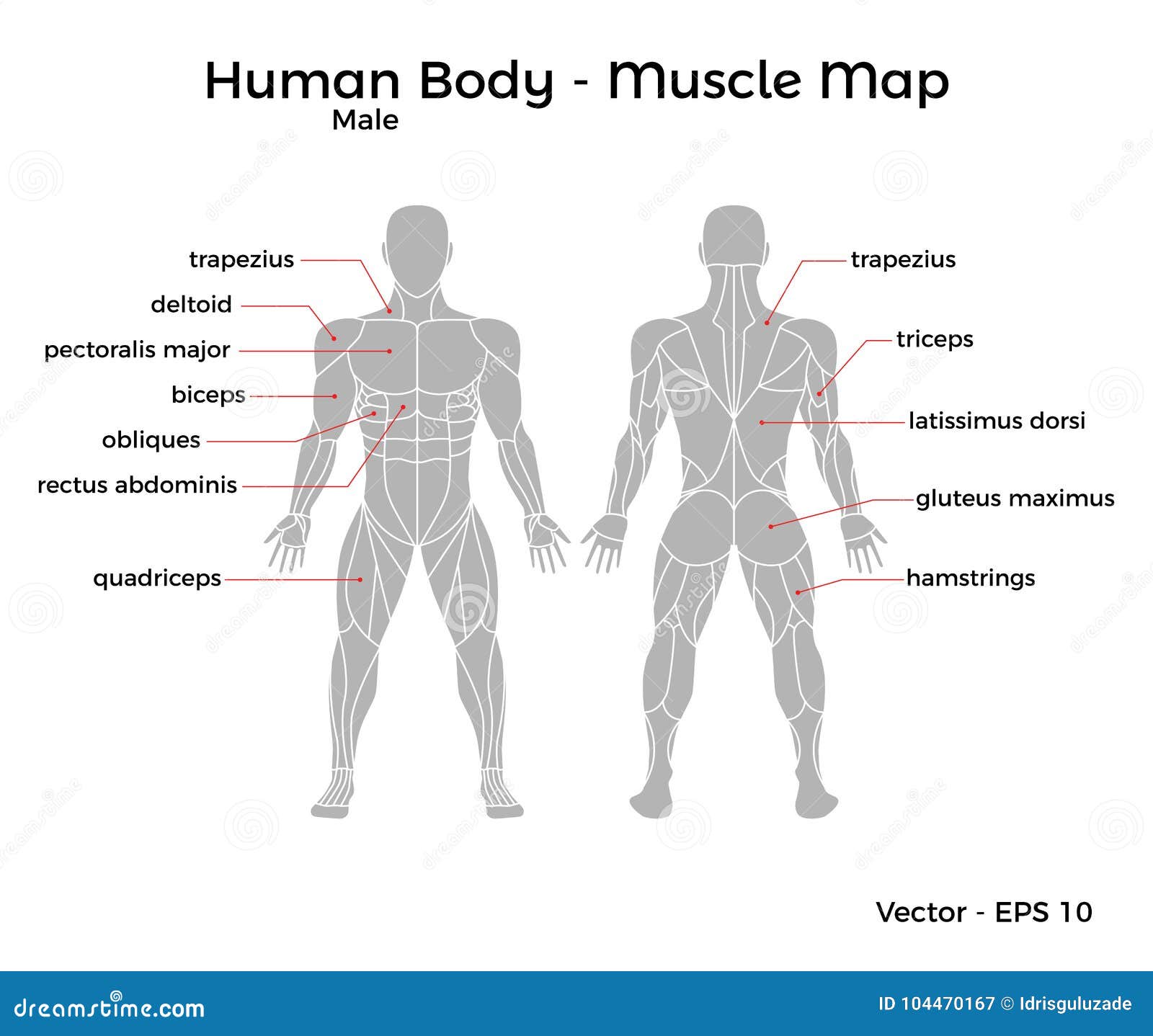

You’ve seen them everywhere. Those glowing, blue-and-red anatomical diagrams plastered on the walls of local CrossFit boxes or flickering on the screen of your favorite fitness app. They look impressive. Scientific. Irrefutable. But honestly, the standard muscle map of the body most of us rely on is a massive oversimplification that ignores how humans actually move. We like to think of our muscles as a collection of isolated rubber bands—biceps do this, quads do that—but the reality is a lot messier and, frankly, way more interesting.

Biology doesn't care about your "arm day" split.

When you look at a professional-grade anatomical chart, like those found in the Netter Atlas of Human Anatomy, you start to realize that "muscle" isn't even a single thing. It’s a nested system. You have over 600 named muscles, sure, but they are all shrink-wrapped in a silver, spiderweb-like tissue called fascia. This fascia connects your pinky toe to your opposite shoulder. If you pull a thread on a sweater, the whole garment bunches up. Your body is exactly like that.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Muscle Map of the Body

We’ve been conditioned to look at the body as a machine with discrete parts. If your knee hurts, you look at the "knee muscles" on the map. Big mistake. Dr. Kelly Starrett, a renowned physical therapist and author of Becoming a Supple Leopard, has spent decades trying to get people to stop looking at the map and start looking at the system. He argues that a "tight" quad is often actually a side effect of a dormant glute or a locked-up ankle.

The map shows you where the muscle sits. It doesn't show you how it behaves.

The Great Posterior Chain Myth

People look at a muscle map of the body and see the hamstrings as these long, vertical strips on the back of the leg. They think, "Okay, if I want better hamstrings, I'll do leg curls." But if you talk to world-class sprint coaches like Dan Pfaff, they’ll tell you that the hamstrings don't just "flex the knee." In a high-speed sprint, they act more like brakes and springs, working in tandem with the gluteus maximus and the spinal erectors.

If your map doesn't show the relationship between your lower back and your heels, it's an incomplete map.

You’ve got layers. Most maps only show the "superficial" layer—the stuff you can see in the mirror. But underneath the "show muscles" like the rectus abdominis (your six-pack) lies the transverse abdominis. It’s a deep, corset-like muscle. You can't see it. You can't really flex it for a photo. But if it’s weak, your back will hurt regardless of how many crunches you do. This is where "mapping" fails the average person: it prioritizes aesthetics over structural integrity.

The Upper Body: A Mess of Overlapping Cables

The shoulder is the most mobile joint in the human body. Because of that, the muscle map of the body in the shoulder region is a nightmare of overlapping tissues. You have the deltoids on top, but underneath, the rotator cuff—the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis—is doing the heavy lifting of keeping your arm bone from flying out of its socket.

📖 Related: Why the EMS 20/20 Podcast is the Best Training You’re Not Getting in School

- The Trapezius: Most people think "traps" are just those bumps next to your neck. Wrong. They actually extend all the way down to the middle of your back.

- The Latissimus Dorsi: These are the "wings." They connect your upper arm to your lower back and pelvis. This is why some people feel back pain when they do pull-ups with bad form.

- The Serratus Anterior: Often called the "boxer's muscle," it sits on your ribs. It looks like fingers. Its job is to pull the shoulder blade forward. If you don't see this on your map, you're missing the key to shoulder health.

It’s easy to get lost in the nomenclature. Latissimus dorsi literally just means "broadest muscle of the back" in Latin. Anatomists weren't being fancy; they were just being descriptive.

Why Your "Core" Isn't Just Your Abs

If you're looking at a muscle map of the body to find your core, stop looking at your stomach. Your core is actually a box. The top is your diaphragm (the muscle that helps you breathe). The bottom is your pelvic floor. The front and sides are your obliques and abdominals. The back is your multifidus and erector spinae.

Think of it like a pressurized soda can. If the can is sealed and pressurized, you can stand on it. It’s incredibly strong. But if you poke a hole in the side—or if one part of that "muscle map" is weak—the whole thing collapses under pressure. This is why "bracing" is more important than "sucking it in."

Real World Application: How to Actually Use This Info

So, you’ve looked at the maps. You know where the pectorals are. Now what?

The biggest takeaway from modern kinesiology isn't about memorizing Latin names. It's about understanding force transmission. When you throw a ball, the force starts in your feet, travels through your legs, crosses your torso via the obliques, and finally exits through your hand. If you have a "dead spot" anywhere on that map—a muscle that isn't firing or is too tight to move—the force leaks out.

You get injured. You plateau. You get frustrated.

The Fascial Lines

Thomas Myers wrote a book called Anatomy Trains. It changed everything. He mapped out "myofascial meridians." Instead of looking at muscles as individual units, he looked at them as continuous lines of pull.

- The Superficial Back Line: Runs from the bottom of your toes, up the back of your legs, over your head, and ends at your forehead. Yes, stretching your hamstrings can actually help a tension headache.

- The Functional Lines: These cross the body in an "X" shape. Your right shoulder is functionally linked to your left hip.

If you're a golfer or a pitcher, this "X" is your power source. A muscle map of the body that doesn't account for these diagonal connections is basically just a 19th-century drawing that hasn't caught up to 21st-century reality.

👉 See also: High Protein in a Blood Test: What Most People Get Wrong

Common Misconceptions That Refuse to Die

We need to talk about "muscle tone." You’ll hear people say they want to "tone" their muscles without making them "bulky." From a physiological standpoint, this is nonsense. Muscles only do two things: they grow (hypertrophy) or they shrink (atrophy). What people call "tone" is actually just a combination of having enough muscle mass and low enough body fat to see it.

The map stays the same; the resolution just changes.

Another one: "Spot reduction." You cannot burn fat off your triceps by doing tricep extensions. You're working the muscle underneath the fat, but the fuel for that work comes from your bloodstream, not the fat cells sitting directly on top of the muscle.

It’s sort of like thinking that by running your car’s heater, you’ll use up the gas specifically in the right side of the tank. Doesn't work that way.

The Mystery of the Psoas

The psoas (pronounced 'so-as') is the only muscle that connects your spine to your legs. It’s deep. It’s hidden. Most people don't even know they have one until it ruins their life. Because it’s so deep, it’s rarely highlighted prominently on a basic muscle map of the body.

If you sit at a desk all day, your psoas is in a "shortened" position. It gets tight. Because it’s attached to your lower vertebrae, it starts pulling your spine forward. Result? Chronic lower back pain. You might spend hundreds of dollars on back massages, but the problem is actually in the front of your hip.

Knowledge is power here. Understanding that your body is a 3D puzzle, not a 2D poster, is the first step to not breaking it.

How to Build a Better Body Map in Your Head

Stop thinking about "muscles" and start thinking about "movements." The brain doesn't recognize individual muscles; it recognizes patterns. When you reach for a glass of water, your brain doesn't say, "Contract the anterior deltoid by 20% and the triceps by 15%." It just says, "Get the water."

✨ Don't miss: How to take out IUD: What your doctor might not tell you about the process

To master your own muscle map of the body, you should focus on the primary human movements:

- Push: Bench press, overhead press, push-ups.

- Pull: Rows, pull-ups, face pulls.

- Hinge: Deadlifts, kettlebell swings (this is all about the hips).

- Squat: Goblet squats, lunges, step-ups.

- Carry: Farmer’s walks or just carrying heavy groceries.

The Role of Proprioception

This is your "sixth sense." It’s your brain’s ability to know where your limbs are without looking at them. You can improve this. Closing your eyes while doing a simple balance exercise forces your nervous system to "update" its internal muscle map.

If your internal map is blurry, your movement will be clunky.

Think of a GPS with a bad signal. You might get to your destination, but you'll take a lot of wrong turns and waste a lot of gas. Improving your mind-muscle connection is basically just upgrading your internal GPS signal.

Actionable Steps for Your Anatomy Journey

Don't just stare at a poster. Use this information to change how you move.

First, stop stretching things that feel "tight" without checking if they are actually weak. Often, a muscle feels tight because it's being stretched thin by a postural imbalance. Stretching it further just makes the problem worse. If your hamstrings always feel tight, try doing some glute bridges. Frequently, once the glutes start working, the hamstrings finally relax.

Second, explore the "blind spots" on your map. Most people focus on the mirror muscles—chest, arms, abs. Spend more time on the stuff you can't see: the rear delts, the glute medius, and the spinal erectors. This is the "armor" that prevents injury.

Third, move in three dimensions. A standard muscle map of the body is a 2D image. But you live in a 3D world. Don't just move up and down or forward and back. Incorporate rotation. Chop wood, throw a med ball, or just do some easy spinal twists.

Finally, listen to the signals. Pain is a data point. It’s your body telling you that the map and the territory don't match up. If a certain exercise hurts, don't just push through it. Look at the surrounding muscles on the map. Find the bottleneck.

Your body is a masterpiece of engineering. Treat it like a high-performance vehicle, not a rental car. The more you understand the underlying structure, the longer you’ll be able to keep it on the road.