Rome was a mess in 44 BC. It wasn't the shiny marble paradise you see in the movies. It was gritty, loud, and politically radioactive. People were terrified. Why? Because Julius Caesar had just been named Dictator Perpetuo—dictator for life. In a city that prided itself on having kicked out kings centuries earlier, that title was basically a death warrant.

The murder of Caesar wasn't some sudden, impulsive act of passion. It was a cold, calculated bureaucratic hit. Think of it as a corporate coup, but with more daggers and less paperwork. Honestly, the conspirators thought they were the heroes of the story. They called themselves the "Liberators." They really believed that by removing one man, the entire Republic would just snap back into place like a broken bone.

They were wrong.

Why the Murder of Caesar Was Inevitable

You've got to understand the vibe in the Senate. These guys were aristocrats. They cared about their "dignitas"—their personal prestige and rank. Caesar was trashing all of that. He was minting coins with his own face on them. He was sitting on a golden throne in the Senate. He was even wearing the purple boots of the old kings of Alba Longa. To guys like Cassius and Brutus, this wasn't just bad politics; it was an existential threat to their way of life.

The conspiracy was huge. We aren't talking about two or three guys in a basement. Over 60 senators were in on it. That’s a lot of people to keep a secret in a city as gossipy as Rome. The fact that Caesar didn't see it coming—or chose to ignore it—is one of the great mysteries of history.

Was he arrogant? Maybe. Or maybe he was just tired. He was 55, which was old for the time, and he likely suffered from temporal lobe epilepsy or a series of mini-strokes. Some historians, like Barry Strauss in his book The Death of Caesar, suggest Caesar might have even known something was up but decided that a dramatic exit was better than a slow decline.

👉 See also: Otay Ranch Fire Update: What Really Happened with the Border 2 Fire

The Logistics of a Political Assassination

Forget the Shakespearean play for a second. There was no "Et tu, Brute?" That's a myth. Most contemporary accounts, like those from Suetonius, suggest Caesar said nothing at all, or if he did, it was a Greek phrase: "Kai su, teknon?" which translates to "You too, child?" It sounds tender, but in the context of the time, it was more likely a curse. Like saying, "Your turn is coming."

The setting was the Theatre of Pompey. The Senate was meeting there because the usual Curia was being rebuilt. Irony is a cruel mistress; Caesar died at the base of a statue of Pompey, his greatest rival.

How it went down:

The plan was simple. Tillius Cimber approached Caesar with a petition about his exiled brother. He grabbed Caesar’s shoulders and pulled down his toga. That was the signal.

"Why, this is violence!" Caesar reportedly yelled.

Then Casca struck. He was nervous. He botched the first blow, hitting Caesar near the neck or shoulder. It was a glancing wound. Caesar fought back. He stabbed Casca with his stylus—the metal pen he used for writing. For a few seconds, it was a brawl. Then the rest of the 60 senators closed in. They were so frantic and disorganized that they actually ended up stabbing each other. Brutus got sliced in the hand.

✨ Don't miss: The Faces Leopard Eating Meme: Why People Still Love Watching Regret in Real Time

They wanted it to be a ritual. A sacrifice. They didn't just want him dead; they wanted him erased. By the time they were done, Caesar had 23 stab wounds. Only one, a thrust to the chest, was actually fatal, according to the physician Antistius who performed history’s first recorded autopsy.

The Massive Miscalculation of the Liberators

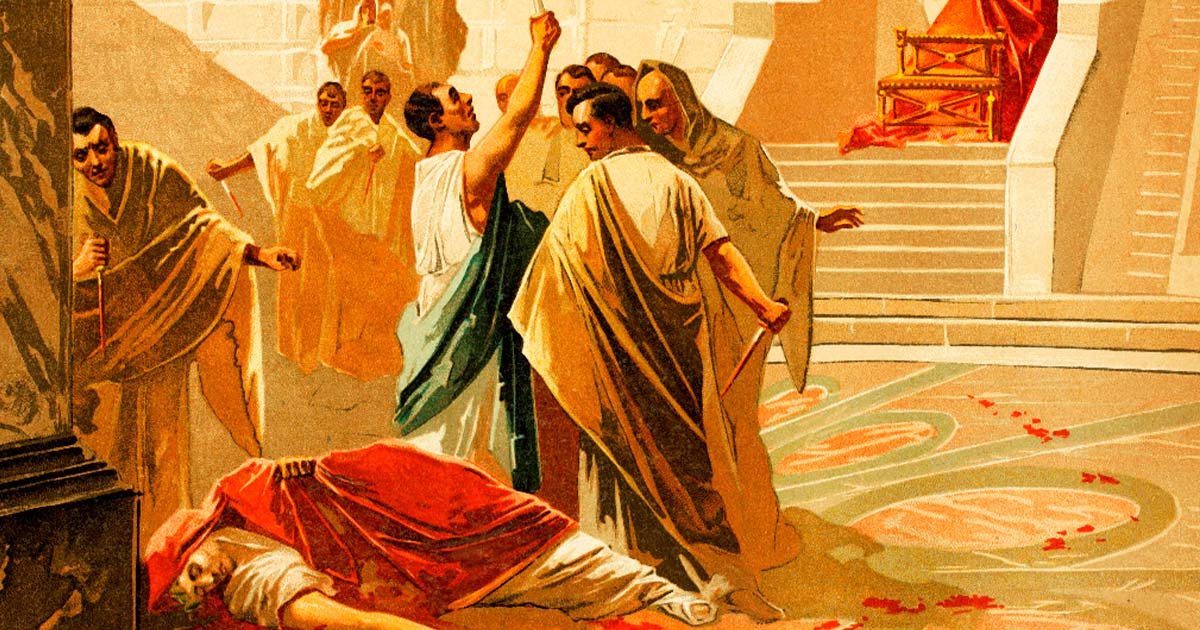

The conspirators thought the crowds would cheer. They walked out of the theater holding their bloody daggers high, expecting a parade. Instead, they met a wall of silence. Then, panic.

The Roman public actually liked Caesar. He gave them grain. He gave them land. He gave them "bread and circuses." When Mark Antony read Caesar's will aloud in the Forum, revealing that Caesar had left a significant sum of money to every single Roman citizen, the mood turned from confusion to murderous rage.

The "Liberators" had to flee the city.

This is the part that gets glossed over in history class: the murder of Caesar didn't save the Republic. It killed it. It created a power vacuum that led to thirteen years of brutal civil war. The Republic didn't return to its glory days. It collapsed into the Roman Empire, led by Caesar’s grand-nephew Octavian (later Augustus).

🔗 Read more: Whos Winning The Election Rn Polls: The January 2026 Reality Check

Misconceptions That Refuse to Die

We need to clear some things up because pop culture has done a number on this event.

- Brutus wasn't Caesar’s son. There were rumors, sure. Caesar had a long-standing affair with Brutus’s mother, Servilia. But the math doesn't work out. Caesar was only 15 or 16 when Brutus was born. It’s unlikely, though their relationship was definitely a weird, twisted mentor-student dynamic.

- The "Ides of March" isn't a spooky date. It was just the 15th of the month. In the Roman calendar, the Ides was a standard deadline for settling debts. The "prophecy" from the soothsayer Spurinna was basically him telling Caesar to watch his back during a high-tension political week.

- It didn't happen in the Capitol. Most people think it happened on the Capitoline Hill. It didn't. It happened in a meeting hall attached to a theater in the Campus Martius.

The Aftermath: A Lesson in Power

If you're looking for a takeaway from the murder of Caesar, it's this: killing a leader is easy; killing an idea is impossible. The conspirators hated the "king," but the Roman people were already over the "Republic." The system was broken long before the daggers came out.

The assassination is a case study in what happens when the elite lose touch with the common person. Brutus and Cassius were obsessed with abstract concepts like Libertas. The guy on the street was obsessed with where his next meal was coming from. Caesar understood that. His killers didn't.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you're visiting Rome or just want to dive deeper into the reality of the Ides of March, here is how to get the real story:

- Visit Largo di Torre Argentina: This is the actual spot. It’s a sunken square in Rome, now famous for being a cat sanctuary. You can see the ruins of the Theatre of Pompey's entrance where Caesar fell.

- Read the Primary Sources: Don't just take my word for it. Check out Plutarch’s Life of Caesar or Suetonius’s The Twelve Caesars. They disagree on the details, which is exactly how you know it's real history—it’s messy.

- Analyze the "Will": Look into the Roman laws of succession. The way Octavian used Caesar’s name to consolidate power is a masterclass in branding. He didn't just inherit money; he inherited a god-like status that he used to dismantle the Senate's power forever.

The Republic died on that floor with Caesar. What rose in its place was something much more stable, but much less free. Whether that was a fair trade is something historians are still arguing about today.

What to do next

Start by looking at the coins from 44 BC. The "EID MAR" denarius issued by Brutus is one of the most famous pieces of political propaganda in history. It features two daggers and a freedman's cap. It is the only coin minted by an assassin to celebrate a murder. Seeing how the conspirators tried to "market" the killing provides a chilling look into the mindset of the men who changed the world with a few inches of steel.