George Stevens didn't just want to make another war movie. He couldn't. When he stepped into the Secret Annex for the 1959 production of The Diary of Anne Frank, he was carrying the weight of what he’d seen as a Signal Corps cameraman during the liberation of Dachau. That’s the thing people forget. This isn't just a "based on a true story" Hollywood flick; it’s a film born from the trauma of the man behind the lens.

It’s been decades since the movie hit theaters. Yet, honestly, it still hits like a ton of bricks. We’ve seen dozens of adaptations since then, including the 1980 TV movie and the 2001 miniseries, but the 1959 version remains the definitive touchstone for a reason. It captured a specific kind of claustrophobia that modern CGI-heavy films often miss. You feel the floorboards creak. You feel the suffocating silence.

What the 1959 Movie Got Right (and What It Softened)

The movie was a massive undertaking. To get the atmosphere right, Stevens insisted on filming in CinemaScope, which is usually for sweeping Westerns or epics. It was a weird choice, right? Using a "wide" format for a tiny attic. But it worked. It stretched the room sideways, making the ceiling look lower and the walls feel like they were closing in on the Frank family and the van Pels.

Millie Perkins, who played Anne, wasn't actually an actress when she was cast. She was a model. Some critics back then thought she was too "Hollywood," but looking back, her wide-eyed innocence captured that specific transition from child to teenager that Anne wrote about so vividly. She had to embody a girl who was literally growing up while trapped in a cage.

However, we have to talk about the "Universalism" of the 1959 script. Written by Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett—who also wrote the stage play—the movie tends to downplay the specific Jewishness of the tragedy to make it more "relatable" to a 1950s American audience. This is one of the biggest critiques from historians today. While the Hanukkah scene is central, the film focuses heavily on the "ideals" of Anne’s spirit rather than the harsh reality of why she was there.

The Casting Masterstroke of Joseph Schildkraut

If you want to know why the movie works, look at Joseph Schildkraut. He played Otto Frank. He had already played the role on Broadway for years. By the time the cameras rolled, he was Otto. There’s a quietness to his performance that is absolutely devastating. He doesn’t play a hero; he plays a father trying to keep his sanity while his world evaporates.

💡 You might also like: Why Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy Actors Still Define the Modern Spy Thriller

Interestingly, Ed Wynn was cast as Mr. Dussell (the real-life Fritz Pfeffer). Wynn was a legendary comedian, and his inclusion added a bizarre, nervous energy to the Annex. It captured the friction of living with strangers. It wasn't all "we shall overcome" moments; it was bickering over food and space and noise. It was messy.

The Haunting Realism of the Set Design

They built the set on a gimbal. They could literally tilt the entire Secret Annex to simulate the shifting perspective or the vibration of bombs falling nearby. The set was a 1:1 scale replica of the actual Prinsengracht 263, but with removable walls for the cameras.

The actors stayed on that set for long periods. Stevens wanted them to look tired. He wanted them to look pale. He reportedly kept the set cold and restricted their movement to mirror the reality of the 25 months the Franks spent in hiding. You can see it in their faces as the film progresses. The skin gets waxier. The eyes get darker. It’s a slow-motion collapse of the human spirit.

- The Soundscape: The movie uses silence as a weapon. In an age of loud blockbusters, the 1959 film forces you to listen to the clock ticking.

- The Ending: Even though everyone knows what happens, the final scene where Otto returns to the attic is a masterclass in restraint. No big orchestral swell—just a broken man and a diary.

Comparing the 1959 Version to Modern Adaptations

A lot of people ask: "Should I just watch the 2001 miniseries instead?" Honestly, the 2001 version (starring Ben Kingsley) is more historically accurate. It doesn't shy away from the horrors of the camps at the end. It includes details about the "betrayal" that weren't known in 1959.

But the 1959 The Diary of Anne Frank has a soul that's hard to replicate. It was made when the wounds of World War II were still fresh. Many of the crew members were veterans. Shelley Winters, who played Mrs. van Daan, actually won an Oscar for her role and later donated her statuette to the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam. That’s how much the project meant to the people involved. It wasn't just a job; it was a memorial.

📖 Related: The Entire History of You: What Most People Get Wrong About the Grain

The movie also handles the relationship between Anne and Peter van Daan with a sort of fragile beauty. In the real diary, Anne’s feelings for Peter shift constantly—from desperate longing to realization that he wasn't quite her intellectual equal. The movie simplifies this into a more traditional romance, which is a bit of a "Hollywood-ism," but it serves the narrative arc of finding light in the dark.

Why the "Most Famous Diary" Faces Modern Scrutiny

There is a weird trend lately where people try to debunk the diary or the film’s portrayal of it. Let’s be clear: the diary is real. The movie is a dramatization, yes, but the core truths are backed by mountains of evidence.

One thing the 1959 movie brushes over is the complexity of Anne’s relationship with her mother, Edith. In the film, it’s portrayed as standard teenage rebellion. In reality, it was much darker and more painful. Anne’s writings about her mother were so harsh that Otto Frank originally edited many of them out of the first published versions of the book. The movie follows the "sanitized" version of their relationship, which is a shame because the real struggle makes Anne feel much more human and less like a saint.

Technical Achievements That Still Hold Up

- Cinematography: Jack Cardiff (one of the greats) did the early work, and the lighting is moody and noir-esque.

- Length: At 170 minutes, it’s a marathon. It’s meant to feel long. It’s meant to make you feel the passage of time.

- The Score: Alfred Newman’s score is haunting, using Jewish liturgical themes without being overbearing.

The Impact on Pop Culture and Education

For many Americans in the 1960s, this movie was their first real confrontation with the Holocaust. It wasn't a documentary; it was a story about a girl who liked movies and complained about her hair. That was the bridge.

When you watch The Diary of Anne Frank, you aren't watching a historical "figure." You're watching a kid who didn't get to grow up. The film's success ensured that Anne’s voice didn't just stay in a notebook—it became a global symbol. Even though some of the dialogue feels a bit dated today (it’s very "theatrical"), the tension of the "Green Police" siren outside is timeless. It still makes your heart skip.

👉 See also: Shamea Morton and the Real Housewives of Atlanta: What Really Happened to Her Peach

How to Experience the Story Today

If you're looking to really understand the context of the movie, you can't just stop at the credits. The film is a starting point, not the whole story.

First, read the "Definitive Edition" of the diary. It contains the passages Otto originally cut, and it paints a much more complex picture of Anne. She was funny, cynical, and sometimes a bit of a brat—which makes her death even more tragic because she was real.

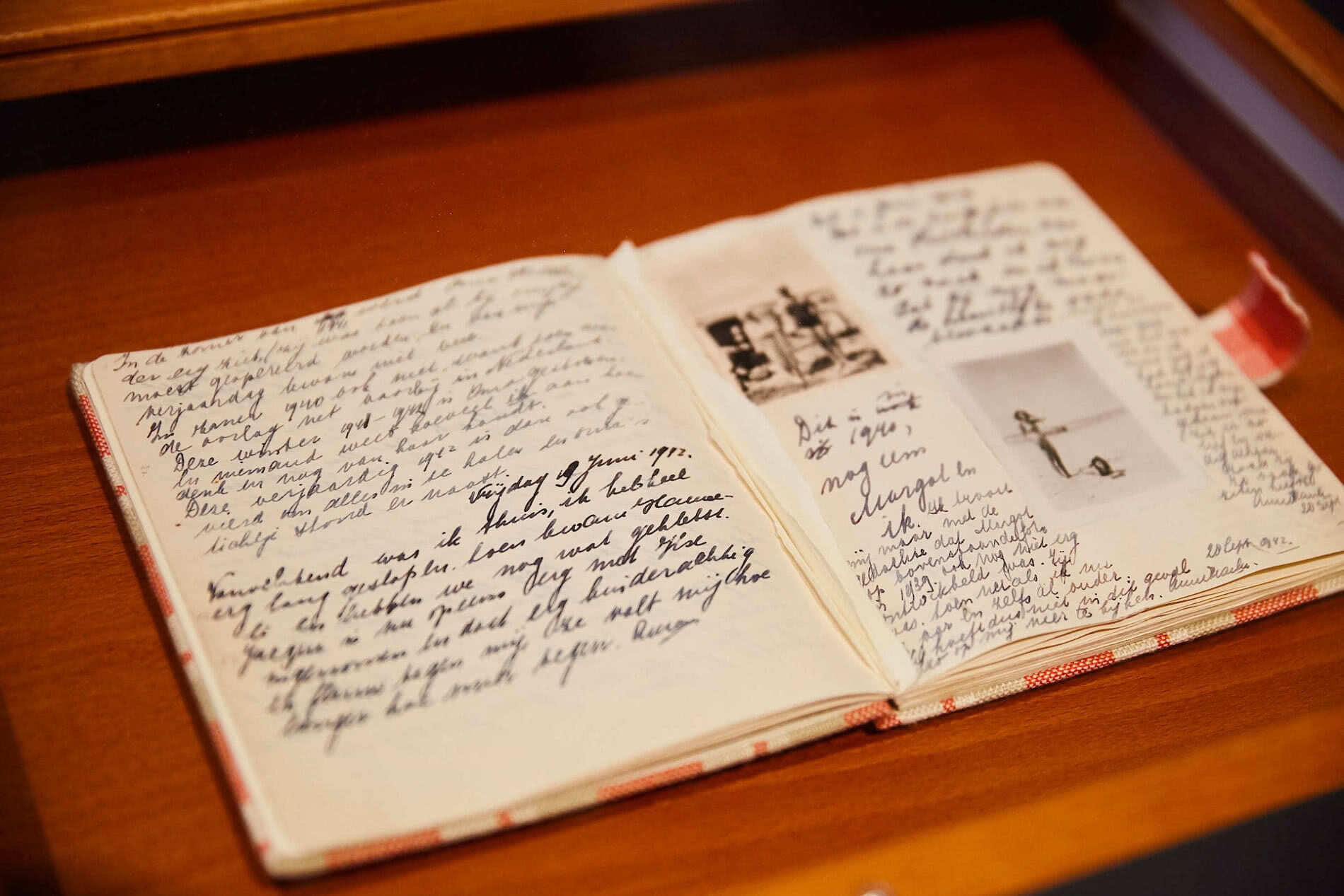

Second, if you ever find yourself in Amsterdam, the Anne Frank House is a must. Seeing the actual space where the movie was set—and realizing it’s even smaller than it looks on screen—is a life-changing experience. The movie did a great job, but nothing replaces the silence of the actual Annex.

Actionable Insights for Viewers and History Buffs

- Watch for the subtle details: Notice how the characters' clothes become baggier and more tattered as the movie progresses. The costume design subtly tracks their starvation.

- Research the "Betrayal": After watching, look into the recent cold case investigations regarding who told the Nazis about the Annex. The movie leaves this as a mystery, but modern researchers have several compelling (and controversial) theories.

- Compare the versions: Watch the 1959 film alongside the 2001 miniseries. Notice what 1950s Hollywood chose to hide versus what 21st-century filmmakers chose to show. It tells you a lot about how our society's relationship with trauma has evolved.

- Support the Anne Frank House: They maintain the archives and provide educational materials worldwide. Engaging with their digital exhibits adds a layer of factual depth that the 1959 film lacks.

The 1959 film ends with Anne's voice saying, "In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart." It's a line that has been debated for decades. Some call it naive; others call it the ultimate act of defiance. Regardless of where you stand, the movie ensures you never forget the girl who said it.

Watch it not just as a piece of cinema, but as a record of how we chose to remember one of history's darkest chapters through the eyes of a child who refused to stop writing.