Antarctica is a place that doesn't forgive mistakes. It’s a white desert. For most people in the 1970s, it was the final frontier, a bucket-list destination that seemed impossible to reach unless you were a scientist or a hardened explorer. Then Air New Zealand changed the game. They started running "flights to nowhere"—luxury sightseeing trips where you could sip champagne in a DC-10 while staring at the Transantarctic Mountains. It was the ultimate travel flex. Until November 28, 1979. That was the day the Mount Erebus plane crash changed aviation safety forever and sparked one of the most bitter legal and political battles in New Zealand's history.

The Illusion of the Whiteout

Here is the thing about flying in Antarctica: your eyes lie to you.

On that morning, Flight 901 took off from Auckland with 257 people on board. They were excited. Capt. Jim Collins and First Officer Greg Cassin were experienced pilots, but they had never flown the Antarctic route before. They weren't worried, though. The flight path was programmed into the computer. They thought they knew exactly where they were.

Except they didn't.

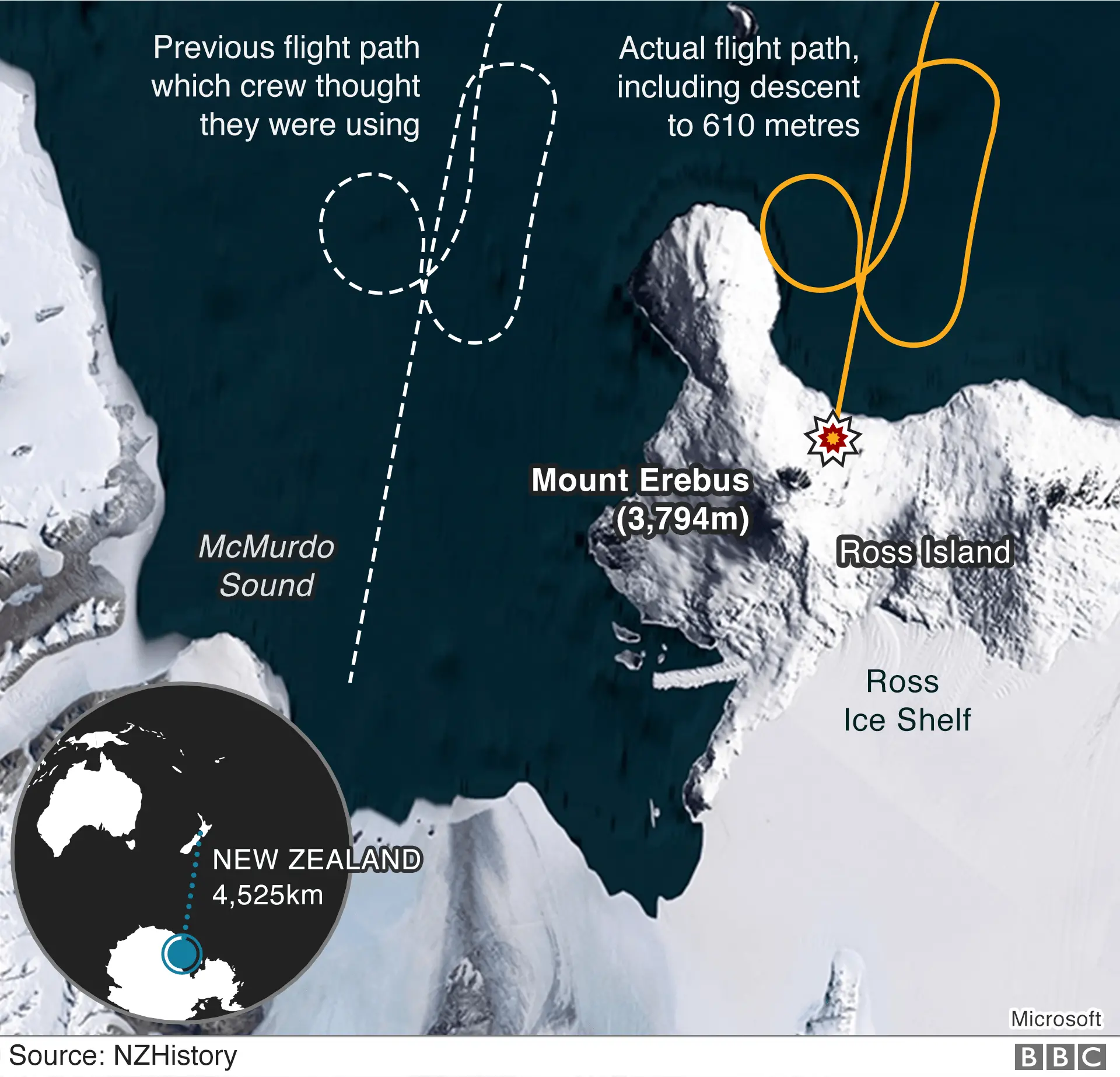

Due to a clerical error the night before, the coordinates in the flight computer had been changed. The pilots weren't told. They thought they were flying down McMurdo Sound, a wide, flat expanse of sea ice. In reality, the plane was heading straight for Mount Erebus, a 12,448-foot active volcano.

You’d think they would see a mountain, right? You’d imagine a giant rock sticking out of the snow. But sector whiteout is a terrifying meteorological phenomenon. When the light hits the uniform white snow and the overhead clouds just right, the horizon disappears. The shadows vanish. To the guys in the cockpit, the white side of the volcano looked exactly like the flat sea ice they expected to see. They were flying level, at low altitude for the tourists to get good photos, completely unaware that a solid wall of rock and ice was seconds away.

💡 You might also like: USA Map Major Cities: What Most People Get Wrong

257 Souls and a Mountainside

The impact was instantaneous.

When the DC-10 hit the lower slopes of Erebus, it wasn't a "crash landing" in any sense that allowed for survival. It was a high-speed disintegration. Everyone on board died in a fraction of a second.

The wreckage was spotted by a U.S. Navy plane hours later. It was a black smear on the pristine white slope. Recovering the bodies was a nightmare. The "Operation Overdue" team, made up of New Zealand police and mountain guides, had to work in sub-zero temperatures, often while the volcano above them puffed out steam and ash. They were working on a 13-degree slope, tagging frozen remains while skuas—predatory birds—circled overhead.

It changed the people who went there. Many of the recovery workers suffered from what we now recognize as severe PTSD. Back then, they just called it a hard job.

The Royal Commission and the "Litany of Lies"

This is where the story gets really messy. Initially, the Chief Inspector of Air Accidents, Ron Chippindale, blamed the pilots. He said they shouldn't have been flying so low. It was "pilot error." Case closed.

📖 Related: US States I Have Been To: Why Your Travel Map Is Probably Lying To You

But Justice Peter Mahon, who led the subsequent Royal Commission of Inquiry, didn't buy it.

Mahon was a sharp guy. He dug into the navigation logs. He discovered that Air New Zealand had changed those coordinates without telling the crew. He realized the pilots were essentially flying a "ghost" track. In a scathing report that is still studied by law students today, Mahon accused the airline's management of a "predetermined plan of deception" and a "conspiracy of silence."

He famously described the airline's defense as "an orchestrated litany of lies."

It was a massive scandal. The airline fought back, and the "litany of lies" phrase was eventually set aside by the courts on technical grounds, but the damage to the public's trust was done. The Mount Erebus plane crash wasn't just a technical failure; it was a corporate one.

Why We Still Talk About Erebus

Why does a crash from 1979 still matter in 2026?

👉 See also: UNESCO World Heritage Places: What Most People Get Wrong About These Landmarks

Because it fundamentally changed how we handle "Controlled Flight Into Terrain" (CFIT). Basically, that's the industry term for when a perfectly functional plane is flown into the ground because the pilots are disoriented. After Erebus, the aviation world got serious about Ground Proximity Warning Systems (GPWS).

It also changed how we look at "Human Factors." It's not just about whether a pilot turned a dial; it's about the system that allowed that pilot to be in a dangerous position without the right information.

What the Industry Learned:

- Trust but Verify: Pilots now receive much more rigorous briefings for "Special Capability" airports and routes.

- Data Integrity: The way flight path changes are communicated is now strictly regulated to prevent the kind of silent update that killed the crew of Flight 901.

- Whiteout Training: Flight crews are taught the physics of light in polar regions. If you can't see the horizon, you don't descend. Period.

Visiting the Site Today

You can't really "visit" the crash site easily. It’s a protected area under the Antarctic Treaty. A stainless steel cross was erected on a rock spur above the site to commemorate the victims. Occasionally, when the snow melts or shifts, bits of the wreckage still emerge—a reminder of a day when technology and nature clashed in the worst way possible.

If you’re a history buff or an aviation geek, the most accessible way to pay respects is the memorial at Waikumete Cemetery in Auckland or the one at Scott Base in Antarctica if you're lucky enough to be a researcher.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Traveler

While luxury sightseeing flights to Antarctica have returned via different carriers (usually departing from Australia), the safety protocols are unrecognizable compared to 1979.

- Check the Operator's History: If you're booking an Antarctic overflight, look for operators with "IAATO" (International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators) membership. They adhere to strict safety and environmental guidelines.

- Understand Technical Limitations: Realize that GPS and standard navigation can still be finicky at the poles due to magnetic interference and satellite coverage. Modern planes use Triple Inertial Navigation Systems, but nature is still the boss.

- Read the Mahon Report: If you're interested in corporate ethics or crisis management, the Mahon Report is a masterclass in investigative rigor. It's widely available online in digital archives.

- Acknowledge the Risk: Travel to extreme environments carries inherent danger. Ensure your travel insurance specifically covers "Antarctic evacuation," which can cost upwards of $150,000.

The Mount Erebus plane crash remains New Zealand’s darkest day in terms of civil disasters. It serves as a permanent warning that even with the best technology, the environment wins if you stop respecting it. Aviation is safer now because of the lives lost on that volcano. That is their legacy.

To dig deeper into the actual flight transcripts or the technical breakdown of the whiteout effect, the New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage maintains an extensive digital archive on the disaster. Looking into the "human factors" element of this crash provides a better understanding of modern air travel safety than almost any other historical event.