Martin Cooper stood on a busy sidewalk in Midtown Manhattan on April 3, 1973, and did something that made people stop and stare like they’d seen a UFO. He pulled out a beige plastic brick the size of a shoebox and called his rival at Bell Labs. He wasn't just making a phone call; he was winning a race. That device, the prototype for the Motorola DynaTAC 8000X, would eventually become the first commercially available mobile phone, but honestly, it was a miracle the thing worked at all.

Most people think mobile phones just appeared out of nowhere in the 80s as sleek status symbols for Wall Street types. They didn't. The journey to the Motorola DynaTAC 8000X was a decade-long slog through regulatory red tape, massive engineering failures, and a literal battle for radio spectrum dominance.

The Phone That Was Basically a Dumbbell

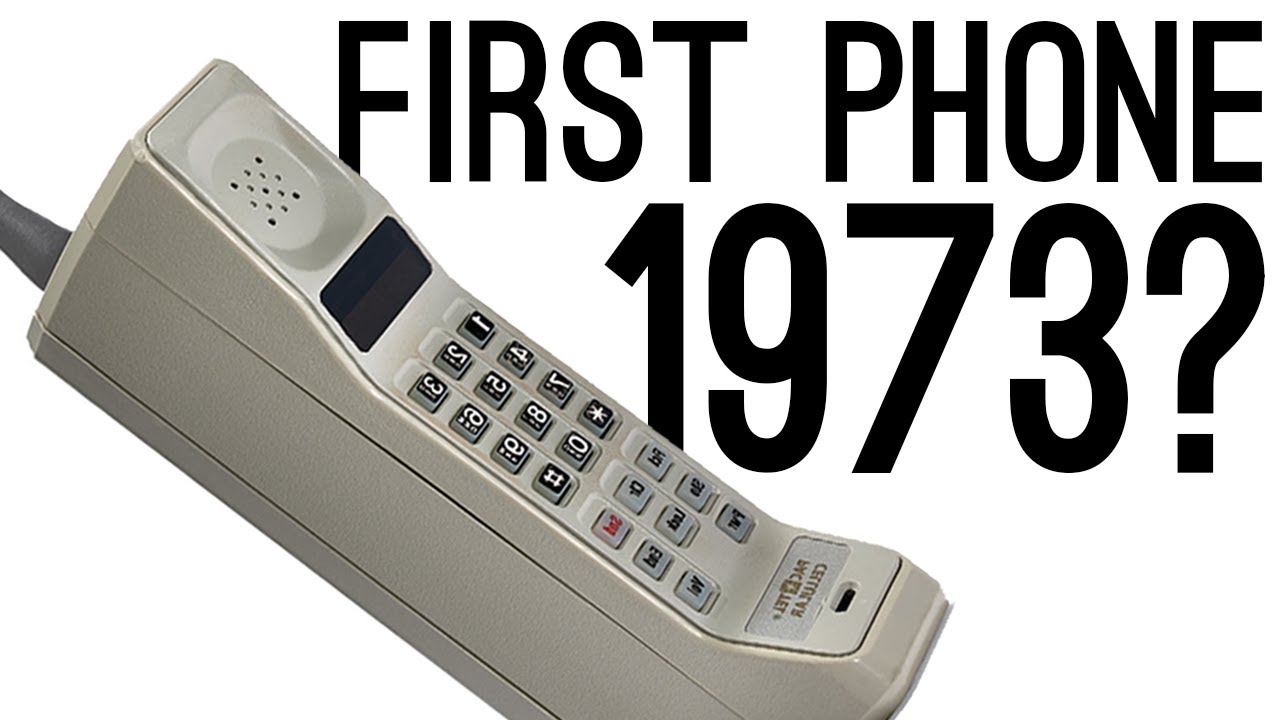

Let's be real about the specs. When the Motorola DynaTAC 8000X finally hit the market in 1983—ten years after that first public demonstration—it weighed 28 ounces. That’s nearly two pounds. To put that in perspective, a modern iPhone weighs about 6 or 7 ounces. Carrying the DynaTAC was less like having a gadget and more like carrying a literal brick in your briefcase.

It was 13 inches high.

It was thick.

It was beige.

And the battery life? It was laughable. You got maybe 30 minutes of talk time before the thing died. Then, you had to plug it in for roughly 10 hours to get it back to full strength. Imagine waiting nearly half a day just to talk for the length of a sitcom episode. Yet, people lined up for them. Thousands of people. Because for the first time in human history, you weren't tethered to a wall or a car. You were reachable anywhere, provided you were standing near a massive cell tower and had the forearm strength to hold the "Brick" to your ear.

What Most People Get Wrong About the "First" Mobile Phone

There's this common misconception that Motorola invented the concept of the cellular network. They didn't. AT&T’s Bell Labs actually came up with the "cellular" concept back in 1947. Their idea was brilliant: instead of one high-powered tower trying to cover a whole city (which is how old radio-phones worked), you’d have a grid of low-power "cells." As you moved, your call would be "handed off" from one cell to the next.

💡 You might also like: Why Your 3-in-1 Wireless Charging Station Probably Isn't Reaching Its Full Potential

AT&T wanted to use this for car phones. They thought the future was in the dashboard.

Motorola, led by Martin Cooper and John F. Mitchell, disagreed. They believed people wanted to be mobile, not just cars. This sparked a legendary corporate rivalry. When Cooper made that famous 1973 call to Joel Engel at Bell Labs, it was a total "I beat you" moment. He literally told Engel he was calling from a "real, handheld, portable cell phone." Engel’s response? Silence. He doesn't even remember the call, or at least that’s what he claimed later.

The $4,000 Price Tag and the Wealth Gap

If you wanted to own a Motorola DynaTAC 8000X in 1984, you needed more than just a desire for tech. You needed a massive bank account. The retail price was $3,995.

Adjusted for inflation today? That is over $11,000.

Think about that. We complain about $1,200 smartphones now, but the first mobile phone cost as much as a decent used car. Because of the price, it became the ultimate "Yuppie" accessory. If you saw someone in a movie like Wall Street or a TV show like Saved by the Bell (Zack Morris, anyone?) using one, it was a shorthand way for the directors to say, "This person is incredibly rich and important."

📖 Related: Frontier Mail Powered by Yahoo: Why Your Login Just Changed

But the service was also a nightmare. You didn’t just pay for the phone; you paid by the minute, often $0.50 or more, plus a hefty monthly fee. There was no such thing as "unlimited data" because there was no data. You could make a call, and that was it. No texting. No clock. Definitely no Snake or Tetris. Just a glowing LED display that showed the number you were dialing.

Why the FCC Almost Killed the Mobile Phone

It’s easy to blame technology for the ten-year gap between the 1973 prototype and the 1983 launch, but the real culprit was the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). They had no idea how to handle the request for radio frequencies.

For years, the FCC sat on the applications. They were worried about monopolies. They were worried about interference with television signals. Meanwhile, Japan and Scandinavia actually beat the U.S. to the punch. The first automated cellular network actually launched in Tokyo in 1979 via NTT. Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden followed with the NMT system in 1981.

America was lagging behind. It took a massive amount of lobbying and the eventual breakup of the AT&T monopoly to finally clear the way for the Motorola DynaTAC 8000X to get its FCC approval. When it finally happened, it triggered a gold rush. Motorola couldn't build them fast enough.

The Engineering Nightmare Inside the Plastic Shell

Building the DynaTAC wasn't just about making a small radio. It was about miniaturizing hundreds of components that used to take up the entire trunk of a car.

👉 See also: Why Did Google Call My S25 Ultra an S22? The Real Reason Your New Phone Looks Old Online

The engineering team, led by Rudy Krolopp, had to figure out how to cram a duplexer (which allows you to talk and listen at the same time), a synthesizer, and a massive battery into a handheld frame. They went through dozens of designs. Some looked like bananas. Some looked like calculators. They eventually settled on the "Brick" because it was the only shape that could actually house the circuit boards without overheating.

The antenna alone was a work of art—a flexible rubber whip that had to be tuned perfectly to the new 800-MHz frequencies the FCC had finally allocated. If you bent it, your signal dropped. If you were inside a building with too much steel, you were out of luck.

The Legacy of the Brick

We owe everything to the Motorola DynaTAC 8000X. Without that overpriced, heavy, beige monster, we wouldn't have the iPhone or the Pixel. It proved that the "personal" in personal communications was a viable business model.

It also changed how we lived. Before the DynaTAC, if you left your house, you were "gone." Nobody could reach you. You were free, or you were lost, depending on how you looked at it. The first mobile phone killed the mystery of where someone was. It started the era of "constant availability," which we’re still trying to figure out how to manage today.

By the time Motorola replaced the 8000X with the slightly smaller 8500X and eventually the MicroTAC (the first "flip" phone), the world had already changed. The "Brick" had done its job. It made the impossible look normal.

How to Apply This History Today

Understanding the origin of the Motorola DynaTAC 8000X isn't just a trip down memory lane; it’s a lesson in how disruptive tech actually enters the world.

- Look for the "Clunky" Phase: If you’re looking for the next big thing (like AR glasses or wearable AI), don't dismiss it just because it looks awkward or expensive right now. Every paradigm-shifting tech starts as a "Brick."

- Infrastructure over Hardware: The phone was useless without the towers. When investing or building in tech, always look at the underlying network—whether that’s 6G, Starlink, or decentralized servers.

- Patience is a Competitive Advantage: Motorola waited 10 years for regulatory approval. If you're building something truly new, the biggest hurdles usually aren't technical; they're legal.

- Value the "Un-tethering": The biggest value proposition of the DynaTAC wasn't "better sound quality"—it was freedom. If you're creating a product, ask yourself if it actually gives the user more freedom or just another chore.

The best way to appreciate your current smartphone is to remember that someone once paid $4,000 for a device that could barely last through a lunch break. We’ve come a long way, but the "Brick" remains the foundation of everything in your pocket.