People talk about "extinction" like it’s this far-off, abstract concept that only happened to mammoths or dodo birds. Honestly? It's happening right now, in real-time, in ways that are kinda terrifying if you look at the numbers. When we talk about the most rare animals in the world, we aren't just talking about a short list of cute critters. We are looking at "ghost species"—animals that are so few in number that they might actually be functionally extinct before you finish reading this sentence.

It’s not just about the big ones, either.

Sure, everybody knows the giant panda (which, luckily, is actually doing a bit better lately), but have you ever heard of the Vaquita? Probably not. It’s a tiny porpoise. It lives in a very specific, very small corner of the Gulf of California. There are likely fewer than ten of them left on the entire planet. Ten. You couldn’t even fill a high school classroom with the remaining population. That’s the reality of rarity in 2026. It’s messy, it’s complicated by illegal fishing and habitat loss, and it’s a race against a clock that doesn't have a pause button.

Why the Most Rare Animals in the World are Vanishing

Biology is brutal. But humans have made it a whole lot faster. Most of these species end up on the "critically endangered" list because they’ve been backed into a corner—literally.

Take the Javan Rhino. You won't find these in a zoo. They only exist in Ujung Kulon National Park in Indonesia. Because they are restricted to one single location, a single natural disaster—like a tsunami or a volcanic eruption from nearby Anak Krakatau—could wipe out the entire species in a single afternoon. That’s a massive amount of pressure on one patch of jungle. According to the World Wildlife Fund and local rangers, there are roughly 76 of them. They are solitary. They are shy. And they are stuck.

Then you have the Saola. Scientists call it the "Asian Unicorn." It was only discovered in 1992. Think about that for a second. We didn’t even know this large mammal existed until the 90s, and now, it’s basically a myth. No biologist has seen one in the wild for years. They live in the Annamite Mountains of Vietnam and Laos. They have these long, straight horns and white markings on their faces that look like war paint.

We don't even know how many are left. It could be a hundred. It could be zero.

The tragedy here is often "bycatch." In the case of the Vaquita, they aren't even the target. Illegal fishers are after the Totoaba (a fish whose bladder sells for a fortune on the black market). The Vaquitas just happen to swim into the nets and drown. It’s a collateral damage extinction. It feels senseless because it is.

🔗 Read more: Entry Into Dominican Republic: What Most People Get Wrong

The Island Effect and Genetic Dead Ends

Isolation is a double-edged sword. Evolution loves islands because they allow for unique, weird adaptations. But for the most rare animals in the world, being stuck on an island is a death trap when things go wrong.

The Kakapo is a perfect example. It’s a parrot, but it’s huge. It’s flightless. It smells like old honey and violin cases—no, seriously, people who handle them say they have a very distinct, musky sweet scent. They evolved in New Zealand where there were no land mammals. Their only defense? Freezing. They just stand still and hope they aren't seen. That worked great against eagles. It worked terribly against the cats and stoats humans brought with them.

The New Zealand Department of Conservation (DOC) has to basically micromanage their entire lives. Every single Kakapo has a name. They have fitness trackers. Rangers monitor their nests 24/7. When they had a fungal outbreak (aspergillosis) a few years ago, it was a national emergency.

- Vaquita: ~10 left.

- Javan Rhino: ~76 left.

- Mountain Gorilla: ~1,000 left (a rare success story).

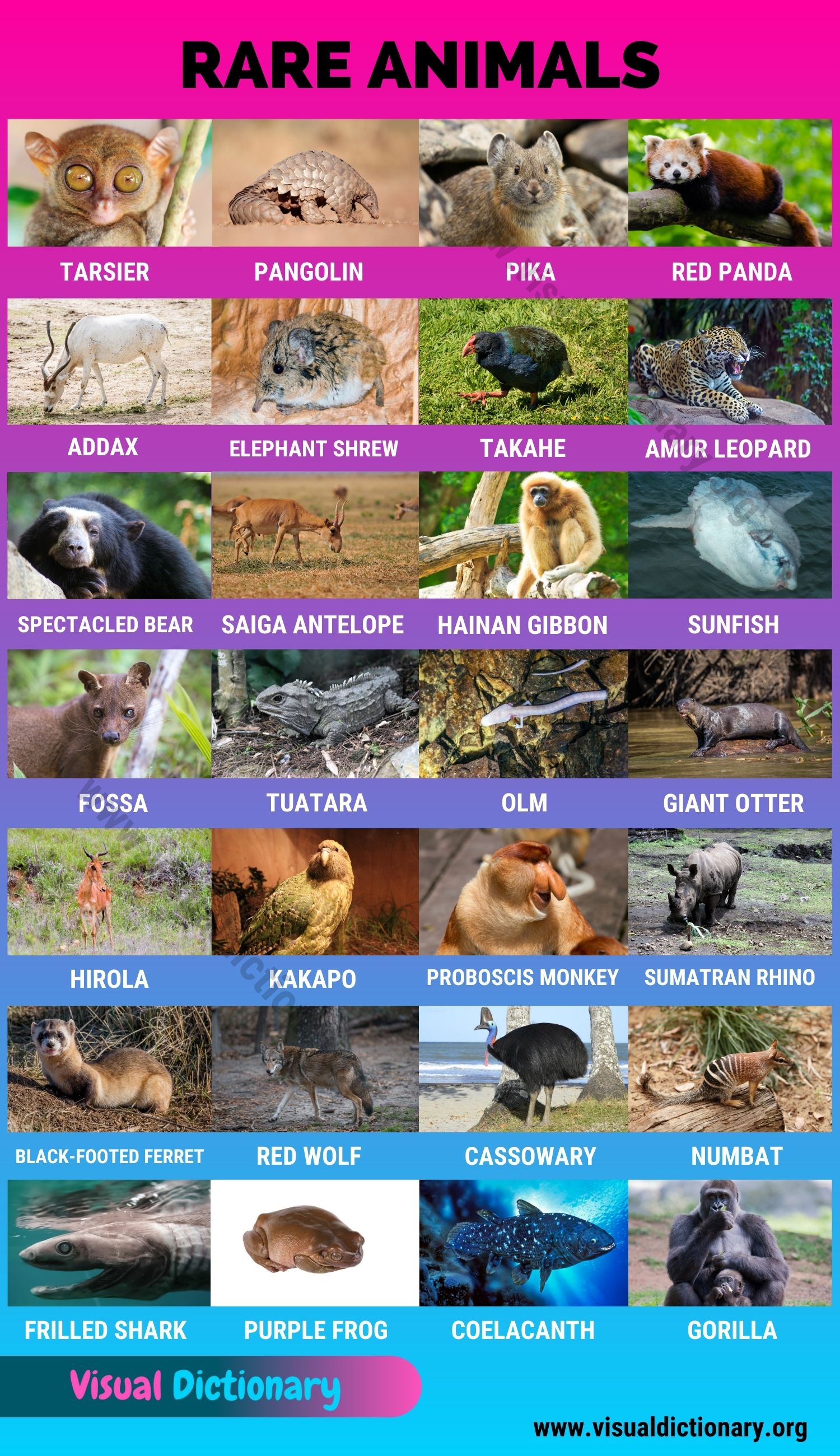

- Addax: Maybe 30-100 in the wild.

If you look at the Addax, a white antelope from the Sahara, it’s a different story. They are perfectly adapted to the desert. They can go months without drinking water. But oil exploration and hunting have pushed them to the absolute brink. They are "extinct in the wild" in many of their former ranges.

The Loneliest Cat: The Amur Leopard

Most people think of leopards as African savanna animals. But the Amur leopard lives in the freezing forests of the Russian Far East and Northern China. They have thick, pale fur and can leap 19 feet horizontally. For a long time, the population was stuck at around 30 individuals.

Imagine trying to keep a species alive with only 30 sets of DNA. Inbreeding becomes a massive problem. Luckily, through insane conservation efforts and a huge protected territory called "Land of the Leopard," the numbers have crawled up to over 100. It’s still one of the most rare animals in the world, but it’s a rare glimmer of hope. It shows that if you give nature a big enough fence and stop shooting things, it can sometimes claw its way back.

Is it Worth the Millions?

There’s a cynical argument out there. People ask why we spend millions of dollars trying to save a tiny porpoise or a flightless parrot. "Extinction is natural," they say.

💡 You might also like: Novotel Perth Adelaide Terrace: What Most People Get Wrong

Well, yeah. It is. But not at this speed.

Current extinction rates are estimated to be 100 to 1,000 times higher than the "background" rate (the natural speed things disappear). When we lose these animals, we lose "evolutionary distinctness." The Aye-aye in Madagascar isn't just a weird lemur; it’s an entire branch of the tree of life. If it goes, there is nothing else like it.

We also have to talk about the Sumatran Elephant. They are smaller than their mainland cousins. They are "ecosystem engineers." They poop out seeds that grow into the trees that capture the carbon that keeps the planet from overheating. When the elephants disappear, the forest changes. When the forest changes, the climate shifts. It’s all connected in a way that’s actually pretty terrifying when you pull on the thread.

The Animals You’ve Never Heard Of

We usually focus on "charismatic megafauna"—the big, cute stuff. But some of the most rare animals in the world are, frankly, kind of ugly or small.

The Red-bellied Heron. The Philippine Crocodile. The Franklin’s Bumblebee.

The Vancouver Island Marmot is another one. It’s basically a giant ground squirrel that lives on a few mountains in Canada. In 2003, there were less than 30 of them. They almost vanished because the clear-cutting of forests changed how they hibernated and moved. Thanks to a massive captive breeding program, they’re back up to about 200. Still rare? Absolutely. But at least they aren't gone.

Then there is the Cross River Gorilla. You’ve probably seen gorillas in documentaries, but these guys are different. They live in a tiny strip of forest between Nigeria and Cameroon. They are incredibly wary of humans—for good reason. There are maybe 200-300 left. They live in rugged terrain that makes it almost impossible for scientists to study them without stressing them out.

📖 Related: Magnolia Fort Worth Texas: Why This Street Still Defines the Near Southside

What Can Actually Be Done?

Stopping the loss of the most rare animals in the world isn't just about donating five dollars to a giant NGO (though that helps). It's about systemic shifts.

The illegal wildlife trade is a multi-billion dollar industry. It ranks up there with drugs and human trafficking. As long as there is a market for rhino horn or pangolin scales, people will take the risk to hunt them. Real change happens when local communities are given a financial reason to keep these animals alive. In Namibia, communal conservancies have actually seen wildlife populations increase because the locals earn more from eco-tourism than they ever did from poaching.

It's also about habitat. You can't save a Javan Rhino if there's no Javan jungle left.

Actionable Steps for the Conscious Traveler and Citizen

If you actually want to make a dent in this, start with your wallet and your influence. This isn't just feel-good advice; it's how the industry shifts.

- Support "Range-State" Tourism: If you're going to travel, go to places where your tourism dollars directly fund park rangers. Look for lodges that are owned by the local community, not international corporations.

- Verify Your Wood and Paper: The destruction of the Sumatran rainforest is driven by pulp, paper, and palm oil. Look for the FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) logo. It’s not a perfect system, but it’s better than the alternative.

- The "Sustainable Seafood" Trap: If you eat fish, use the Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch. Avoiding gillnet-caught fish is the only way to reduce the pressure on species like the Vaquita.

- Pressure the Tech Platforms: A lot of illegal wildlife trade happens on social media and e-commerce sites. Report any listings for "exotic" skins or bones.

The reality of the most rare animals in the world is that their survival is a choice we are making every day. It’s a choice in the products we buy and the policies we support. These animals are the "canaries in the coal mine" for the planet's health. If they can't survive, eventually, we won't be able to either. It’s not just about saving a rhino; it’s about saving the systems that keep us all alive.

We are currently the stewards of a disappearing world. Whether these animals remain "the most rare" or become "the most remembered" is entirely up to the actions taken in the next ten years. The window is closing, but it isn't shut yet.