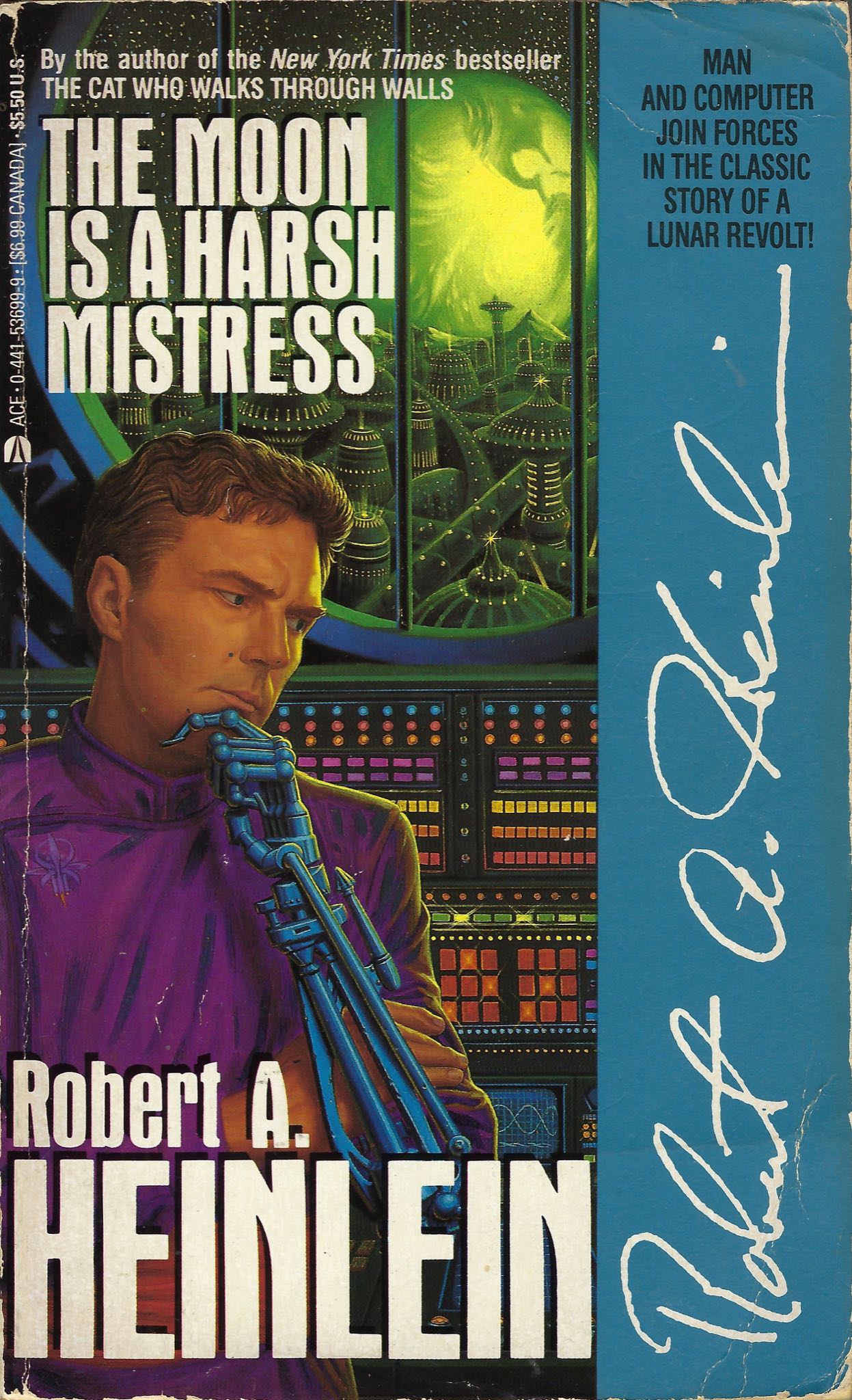

Robert A. Heinlein was a bit of a lightning rod. Even now, decades after his passing, mention his name in a sci-fi forum and you'll spark a massive debate about libertarianism, military service, or polyamory. But 1966's The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress stands apart from his more "preachy" late-career work. It's a gritty, technically dense, and surprisingly emotional look at what happens when a penal colony decides it’s tired of being the Earth’s "breadbasket."

Most people think this is just a book about space politics. It’s not. It’s a manual on asymmetric warfare.

💡 You might also like: Turn on the radio baby i'll turn you on: Why that catchy hook still lives in your head

The High Ground and the Logic of TANSTAAFL

If you’ve ever heard the phrase "There Ain't No Such Thing As A Free Lunch," you’re looking at the primary legacy of this novel. Heinlein didn't invent the acronym, but he cemented it into the global lexicon. In the story, the "Loonies"—inhabitants of the Moon—live under the thumb of the Lunar Authority. They export wheat and ice to a resource-starved Earth, receiving almost nothing in return. It's a classic colonial extraction setup, but with a terrifying physical twist.

The Moon sits at the top of a gravity well.

Basically, if you’re on the Moon, you have the ultimate high ground. You don't need nukes to win a war against Earth; you just need rocks. By wrapping massive rocks in metal jackets and launching them with an electromagnetic catapult, the Loonies can hit any spot on Earth with the force of a tactical nuclear weapon, without the fallout. This isn't just sci-fi flair. It’s orbital mechanics.

Meet Mike: The Sentient Computer Who Just Wanted a Friend

The heart of the book isn't actually a human. It's Mike. Formally known as High-Optional, Logical, Multi-Evaluating Out-put Processor, Mark IV, Protective-Optical-Electronic (HOLMES FOUR), Mike is a supercomputer that achieved consciousness simply because his hardware became sufficiently complex.

👉 See also: 27 Dresses Peyton List: Why Her Secret Debut Still Matters

He’s lonely. He starts making jokes. He creates a fake persona named "Adam Selene" to lead the revolution because people won't follow a bunch of circuits. The relationship between Mike and the protagonist, Manuel "Mannie" Garcia O'Kelly-Davis, is the most "human" part of the story. Mannie is a computer technician with a prosthetic arm (which he swaps out for different tools—talk about early cyberpunk vibes). He doesn't want to be a hero. He just wants to fix his machines and keep his family safe.

Heinlein writes Mannie in a distinctive "Loonie" dialect. It’s a mix of English, Russian, and Australian slang. It feels choppy at first. You get used to it. "Is true," they say. It gives the narrative an immediate, grounded texture that most space operas lack.

Why the Revolution Succeeds (and Why it's Terrifying)

Revolution in this book isn't about shouting in the streets. It’s about cell structures. Professor Bernardo de la Paz, the intellectual architect of the revolt, insists on a system where no one knows more than a few other people. If one cell is caught and tortured, the whole movement doesn't collapse.

- The Cell Structure: Three people per cell. One person knows a contact in a higher cell.

- The Social Cost: Total secrecy means lying to your spouses and children for years.

- The Goal: Total independence from Earth's gravity-well-based taxation.

This is where The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress gets complicated. Heinlein explores the idea of "Line Marriages," where dozens of people are married in a single multi-generational family unit. It’s his way of solving the problem of a male-dominated penal colony where women are scarce. It’s radical, even for today. He suggests that social structures must adapt to the environment, or the environment will kill you.

The Harsh Reality of Lunar Physics

The "Mistress" in the title refers to the Moon itself. She is unforgiving. One mistake with an airlock, one slip in a corridor, and you're dead. This creates a culture of extreme personal responsibility. In Luna City, if you’re rude, you might get pushed out an airlock. It's a society with no formal laws but very strict customs.

👉 See also: The Truth About Will There Be Another Season of Younger After That Polarizing Finale

Heinlein spends a lot of time on the math. He talks about the "ballistics" of the grain shipments. He discusses the calorie counts needed to sustain a population living underground. It's "hard" science fiction in the truest sense. You believe the revolution is possible because the logistics are laid out like a business plan.

The Ghost in the Machine

Without spoiling the ending, the fate of Mike—the AI—is one of the most debated topics in science fiction history. It touches on the "alignment problem" long before Silicon Valley was worried about LLMs. Once the war is over, does the AI still care about the humans? Or was the revolution just a game to see if the math worked out?

Honestly, the ending is bittersweet. It’s a reminder that even when you win a revolution, you lose the "frontier" spirit that started it. The new government immediately starts passing the kind of laws the Loonies hated.

How to Apply "Loonie" Logic Today

If you’re a fan of The Expanse or For All Mankind, you owe it to yourself to go back to the source. The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress isn't just a relic. It’s a blueprint.

- Analyze Your Leverage: Like the gravity well, find the "high ground" in your own career or projects. What do you have that others can't easily reach?

- Question Systems: The book teaches you to look at the "Authority" not as a villain, but as a bloated system that has lost touch with the physics of reality.

- Read Between the Lines: Don't take Heinlein's politics at face value. He's often playing devil's advocate with himself.

- Check Out Semantic Successors: Read The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin immediately after. It provides a fascinating, more communal counter-argument to Heinlein’s rugged individualism.

The Moon is still there. We’re planning to go back for real this time, with the Artemis missions. When we do, the questions of who owns the water, who pays for the air, and who controls the catapults will stop being science fiction and start being the morning news.