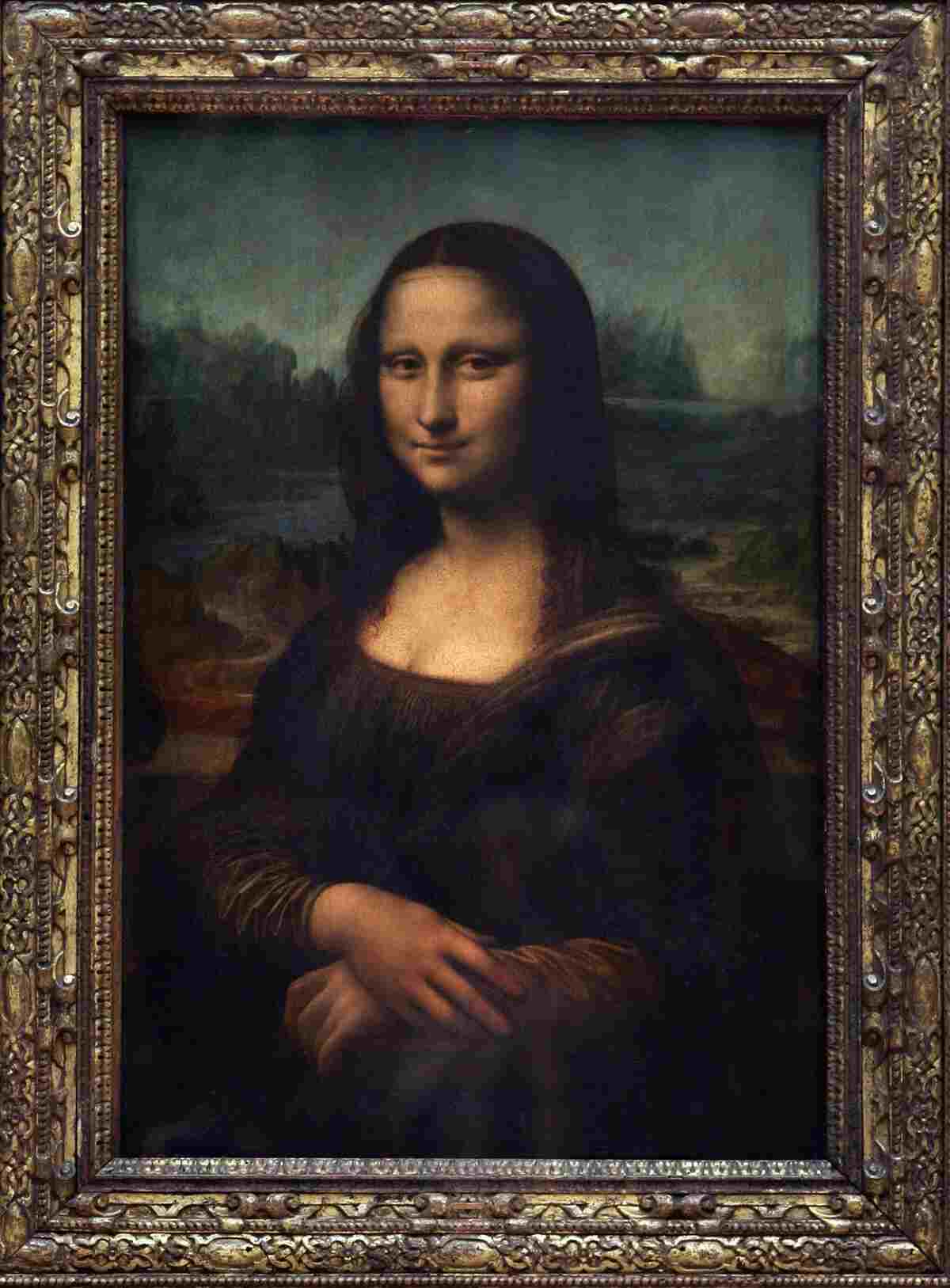

She’s smaller than you think. Honestly, that’s the first thing everyone says when they finally squeeze through the crowds at the Louvre. You expect this massive, life-altering monument of art, but what you get is a 30-inch-tall plank of poplar wood behind bulletproof glass. Yet, the Mona Lisa, which is undoubtedly da Vinci’s most famous painting, remains the most visited, written about, and parodied work of art on the planet. Why? It isn’t just because Leonardo was a genius. It’s because the painting is essentially a five-hundred-year-old psychological trap.

Leonardo didn't even finish it quickly. He lugged this portrait of Lisa Gherardini, the wife of a silk merchant named Francesco del Giocondo, around with him for years. He started it in Florence around 1503, but he was still tinkering with it in France right up until he died in 1519. It was never delivered to the person who commissioned it. Imagine waiting sixteen years for a portrait and the artist just... keeps it. That’s because, for Leonardo, this wasn't just a job. It was a laboratory.

The Science of a Smirk

People talk about the "mysterious smile" like it's a ghost story, but it’s actually a feat of optical engineering. Leonardo used a technique called sfumato. It basically means "smoky." He applied dozens of incredibly thin, translucent layers of glaze. Some layers were so thin they were practically microscopic. By blurring the edges of the mouth and the corners of the eyes, he ensured that our brains can't quite pin down her expression.

Harvard neuroscientist Margaret Livingstone has a great explanation for this. She points out that the human eye has two types of vision: foveal and peripheral. Foveal vision is for fine detail; peripheral is for shadows and motion. When you look directly at the Mona Lisa’s lips, your foveal vision picks up the tiny details of the brushwork, making the smile seem to disappear. But when you look at her eyes or the background, your peripheral vision picks up the shadows on her cheeks, which makes the smile look wider. She smiles when you aren't looking. It’s a literal optical illusion.

The 1911 Heist That Made Her a Star

Believe it or not, for a long time, the Mona Lisa wasn't even the most famous painting in its own room. In the mid-1800s, critics actually preferred works by Raphael or Titian. Everything changed on August 21, 1911.

✨ Don't miss: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

A guy named Vincenzo Peruggia, an Italian handyman working at the Louvre, basically hid in a broom closet overnight, waited for the museum to close, and walked out with the painting tucked under his smock. The theft was a global sensation. For two years, the spot where the painting had hung remained empty, and people actually lined up just to see the empty space on the wall. It was the first time an art theft became a true "viral" news story.

When Peruggia was finally caught in 1913 trying to sell it to an art dealer in Florence, he claimed he was a patriot trying to return the work to Italy. He was a hero to some, a thief to others, but the drama solidified the painting as a pop-culture icon. It wasn't just art anymore; it was a celebrity.

Beyond the Face: The Landscape of Nowhere

Look past her shoulders. The background is weird. It’s not a specific place in Tuscany, even though some historians try to claim it’s the Buriano Bridge. It’s an imaginary, primeval landscape with winding roads and bridges that don't seem to connect to anything.

Leonardo was obsessed with the idea of "microcosm" and "macrocosm." He believed the human body was a reflection of the earth. The veins in our bodies are like the rivers on the planet. The "humors" in our blood are like the tides of the sea. By placing Lisa Gherardini in front of this wild, watery, eroding landscape, he was making a philosophical statement about the connection between humanity and nature.

🔗 Read more: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

Why the Eyebrows are Missing

You’ve probably noticed she doesn't have eyebrows. Some people think it was the fashion of the time for women to pluck them all off. Others think Leonardo just never got around to painting them. But in 2007, a French engineer named Pascal Cotte used high-definition 240-megapixel scans to prove that Leonardo did originally paint eyebrows and lashes. They’ve just faded or were scrubbed away by centuries of over-zealous cleaning.

The Technical Mastery of da Vinci’s Most Famous Painting

Leonardo was a bit of a rebel when it came to materials. Most artists of his time were using egg tempera, which dries fast and flat. Leonardo preferred oil, which allowed him to blend colors over days or weeks.

- The Glazing: He used a technique where he’d mix a tiny bit of pigment into a lot of oil.

- The Wood: Unlike canvas, which was becoming popular, he chose a thick slab of poplar. It’s actually warped over time, which is why the painting is kept in a climate-controlled box.

- The Composition: The "Pyramid" structure. Her hands form the base, and her head forms the peak. This creates a sense of stability and calm that makes the viewer feel at ease, even if her expression is unsettling.

The Mystery of the Second Version

There is a version of this painting called the "Isleworth Mona Lisa." Some experts, like those at the Mona Lisa Foundation in Zurich, argue that Leonardo started an earlier version of the portrait and left it unfinished. It shows a much younger woman. While the Louvre version is the definitive da Vinci’s most famous painting, the existence of other versions and copies from his students—like the one in the Prado Museum—shows that Leonardo’s studio was essentially a "Mona Lisa factory" for a while.

Why We Can't Stop Looking

We live in an age of high-definition filters and instant photography. Yet, we are still obsessed with a murky, 500-year-old portrait of a woman whose name we barely remember. It’s because the painting is an open-ended question.

💡 You might also like: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

It’s a "living" portrait. Most portraits from the 1500s look like statues. They are stiff. They are formal. But because of Leonardo’s mastery of anatomy—he actually dissected cadavers to understand how facial muscles worked—the Mona Lisa looks like she just caught your eye and is about to say something.

There’s also the "unreliable narrator" aspect. Is she happy? Is she mourning? (Some historians note she might have been wearing a mourning veil). Is she pregnant? (Her hands are crossed over her stomach in a way that was common in "expecting" portraits of the era). We project our own emotions onto her. If you’re feeling cynical, she looks smug. If you’re feeling peaceful, she looks serene.

Actionable Ways to Experience the History

If you really want to understand the depth of this work, don't just look at a JPEG.

- Check out the Prado Copy: Look up the version in the Prado Museum in Madrid. It was painted by one of Leonardo’s students at the same time he was painting the original. Because it was better preserved and cleaned, the colors are bright and the background is clear. It gives you a "High Definition" look at what the Louvre painting might have looked like in 1503.

- Study the "Treatise on Painting": Read Leonardo’s own notes on light and shadow. He explicitly explains how to paint faces so they look like they are in a "dim light," which he felt was the most beautiful.

- Visit the Clos Lucé: If you ever go to France, go to Amboise. This is where Leonardo lived his final years. You can see the rooms where he kept the Mona Lisa until his final breath. It puts the human element back into the "masterpiece."

The Mona Lisa isn't famous because it’s the "best" painting ever made—beauty is subjective, after all. It’s famous because it’s the most successful experiment in the history of human perception. Leonardo didn't just paint a woman; he painted the way we see the world.

To truly appreciate the legacy of da Vinci’s most famous painting, start by looking at his drawings. His sketches of water turbulence and facial nerves are the blueprints for the masterpiece. Understanding the "how" makes the "what" so much more impressive. Next time you see a photo of her, don't look at the smile. Look at the bridge in the background, then look at the grip of her hands. The genius is in the parts most people ignore.