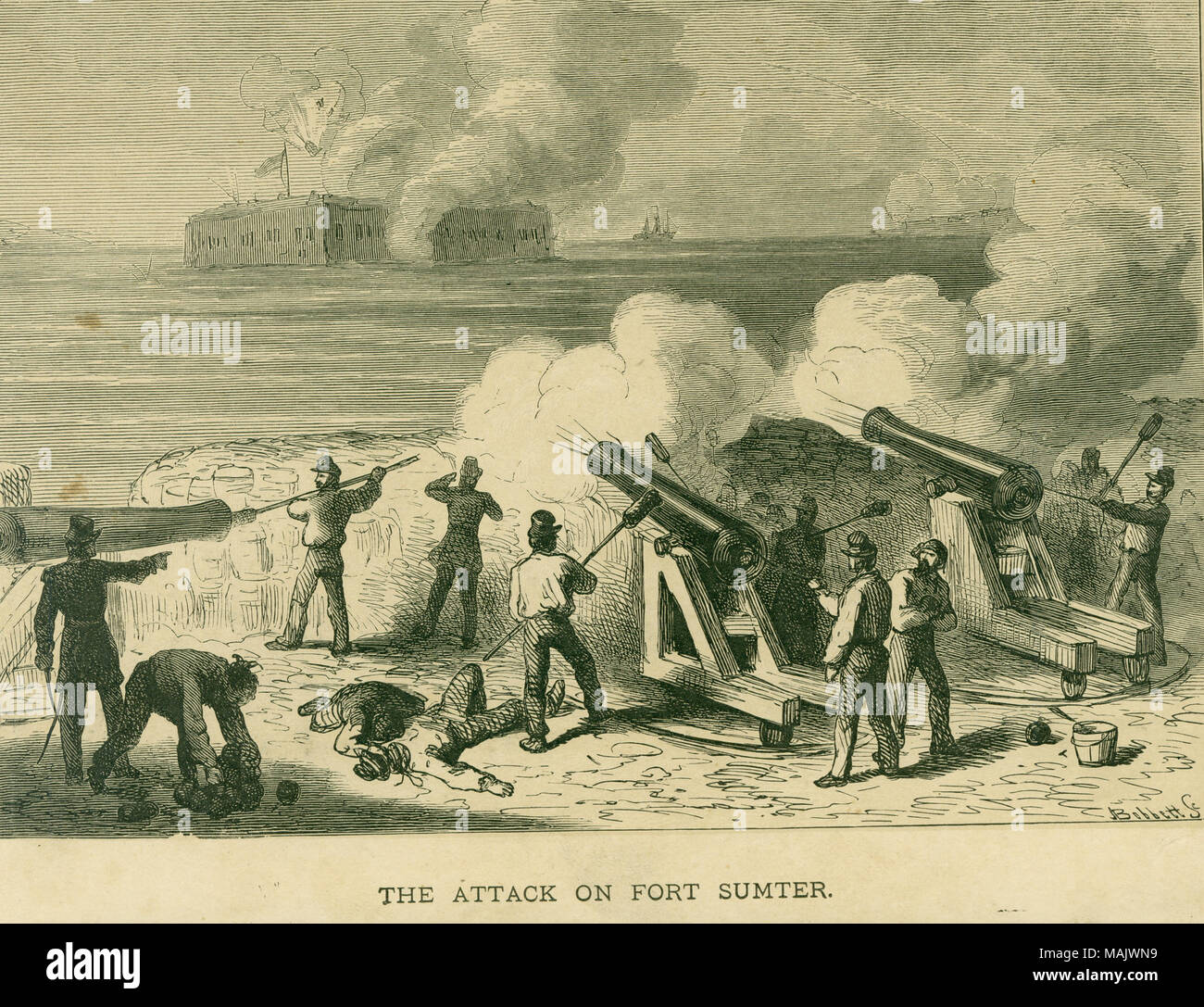

It was 4:30 in the morning. April 12, 1861. Most people in Charleston, South Carolina, were fast asleep, but the soldiers at Fort Johnson were wide awake, pulling the lanyard on a 10-inch mortar. That single shell arched through the dark sky and exploded directly over a masonry island in the middle of the harbor. If you’ve ever wondered when did the attack on fort sumter happen, that’s your answer down to the minute. It wasn't just a skirmish. It was the "terrible swift sword" finally being drawn.

The blast didn't just wake up the city; it signaled the end of decades of bickering, failed compromises, and political posturing. For 34 hours, the world watched as the United States began to tear itself apart.

Honestly, the timeline of the attack is kind of a mess if you don't look at the weeks leading up to it. It wasn't a surprise. Everyone knew something was coming. They just didn't know if Abraham Lincoln would fold or if Jefferson Davis would blink first. Neither did.

The Ticking Clock of April 1861

By the time the first shot was fired on April 12, the situation at Fort Sumter was basically a hostage crisis. Major Robert Anderson, the Union commander, was trapped. He had about 85 men and was running out of salt pork and hardtack. He was surrounded by Confederate batteries that had been popping up like weeds all around the harbor.

Lincoln had a nightmare on his hands. If he reinforced the fort with more troops, he’d be the aggressor. If he evacuated, he’d look weak and basically admit the Confederacy was a real country. He took a middle path: he told the Governor of South Carolina he was sending "provisions only." No guns. No extra soldiers. Just food.

The Confederates saw through it. They didn't care about the crackers or the bacon. They saw the presence of a U.S. fort in their premier harbor as a slap in the face to their claim of independence. On April 11, three Confederate aides rowed out to the fort to demand a surrender. Anderson said no. He told them he’d be starved out in a few days anyway, but he wouldn't quit.

👉 See also: The Ethical Maze of Airplane Crash Victim Photos: Why We Look and What it Costs

The messengers went back, consulted with Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard—who, in a weird twist of history, had actually been Anderson’s student at West Point—and returned at 3:20 AM on the 12th. They told Anderson the firing would start in one hour.

34 Hours of Fire and Iron

When the bombardment started at 4:30 AM, it wasn't a quick affair. It was slow. Methodical. The Confederates had about 43 guns and mortars pointed at that one little island. Anderson, being low on gunpowder, didn't even fire back for nearly three hours. He waited until 7:00 AM, when Captain Abner Doubleday—the guy people wrongly think invented baseball—fired the first Union shot in response.

The weather was rough. Rain was coming down. The fort’s barracks caught fire multiple times. It’s hard to imagine the heat inside those brick walls. The smoke was so thick the soldiers had to lie face-down on the ground and breathe through wet cloths just to keep from suffocating.

By the afternoon of April 13, the situation was hopeless. The main gates were burned. The magazine (where the gunpowder was kept) was dangerously close to exploding. A private citizen named Louis Wigfall actually rowed out to the fort under a white flag—without the General's permission, mind you—to ask if they were done yet.

Anderson finally agreed to a "truce" at 2:30 PM on Saturday, April 13.

✨ Don't miss: The Brutal Reality of the Russian Mail Order Bride Locked in Basement Headlines

The Strange Casualties of the Attack

Here is a fact that almost sounds like a lie: nobody died during the actual battle.

Thousands of shells were fired. Buildings were leveled. The fort was a ruin. Yet, not a single soldier on either side was killed by enemy fire during those 34 hours. The only deaths happened after the surrender. During a 100-gun salute to the U.S. flag before they evacuated, a pile of cartridges accidentally blew up. Private Daniel Hough was killed instantly, and another soldier, Edward Galloway, died later from his wounds.

It’s a grim irony. The bloodiest war in American history started with a "bloodless" opening act, only to end with over 600,000 dead.

Why the Timing of the Attack Changed Everything

When news of the fall of Sumter hit the North on April 14 and 15, the mood shifted instantly. Before the attack, many Northerners were fine with letting the South go. "Let the erring sisters depart in peace," was a common sentiment.

But the attack on the flag changed the math. On April 15, Lincoln issued a proclamation calling for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the rebellion. That move actually forced the "Upper South"—states like Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee—to finally choose sides. They chose the Confederacy.

🔗 Read more: The Battle of the Chesapeake: Why Washington Should Have Lost

If the attack hadn't happened when it did, or if the North had evacuated the fort peacefully, the war might have looked very different. It might have been shorter. Or maybe it wouldn't have happened at all in 1861. But that 4:30 AM wake-up call made the conflict unavoidable.

Misconceptions About the Date

A lot of people think the war started the day Lincoln was inaugurated (March 4) or the day South Carolina seceded (December 20, 1860). Those were political starts, sure. But the shooting match—the actual "point of no return"—is strictly April 12, 1861.

Another common mix-up is where it happened. People often confuse Fort Sumter with Fort Moultrie. Actually, Anderson’s troops were originally at Fort Moultrie, but they snuck across the water to Sumter in the middle of the night on December 26, 1860, because Sumter was much easier to defend. That move by Anderson actually infuriated the South and set the stage for the April showdown.

Visiting the Site Today

If you go to Charleston today, you can take a boat out to the fort. It’s a National Park now. It looks different than it did in 1861; it’s much shorter because the Union actually spent years shelling it back from the Confederates later in the war, grinding the brick walls down to rubble.

Standing on those parade grounds, you get a sense of how small the world must have felt for those 85 men. You can still see some of the massive cannons and even some shells stuck in the walls. It’s a quiet place now, which is a weird contrast to the chaos of that Friday morning in April.

What to Do Next to Understand the History

If you're looking to dive deeper into the reality of the Sumter attack, skip the generic textbooks. There are a few specific things you should do to get a "human" look at the event:

- Read the official dispatches: Look up the telegrams sent between Major Anderson and the War Department. The tone shifts from professional to desperate in a span of just 48 hours.

- Study the "Star of the West" incident: Most people don't realize there was a "pre-attack" in January 1861 where South Carolina cadets fired on a supply ship. It’s the forgotten prologue to the April 12 bombardment.

- Examine the "Great Compromise" attempts: Research the Crittenden Compromise to see just how close the U.S. came to avoiding the attack on Fort Sumter entirely.

- Track the 1861 timeline: Use a map of Charleston Harbor to see where the floating batteries were located. It makes you realize that Fort Sumter was basically in a crossfire from every single direction.

The attack on Fort Sumter wasn't just a date in a history book. It was a failure of diplomacy and a triumph of passion over reason. When those guns opened up at 4:30 AM, they didn't just break the silence of the harbor; they broke the country. Knowing the timeline helps us understand how quickly a "cold war" can turn hot when people stop talking and start shooting.