If you ask a third-grader to name the longest river in US history books, they’ll probably shout "Mississippi!" without even thinking. Most people do. It’s the one with the catchy spelling and the Mark Twain vibes. But honestly? They’re wrong.

The Missouri River is actually the longest.

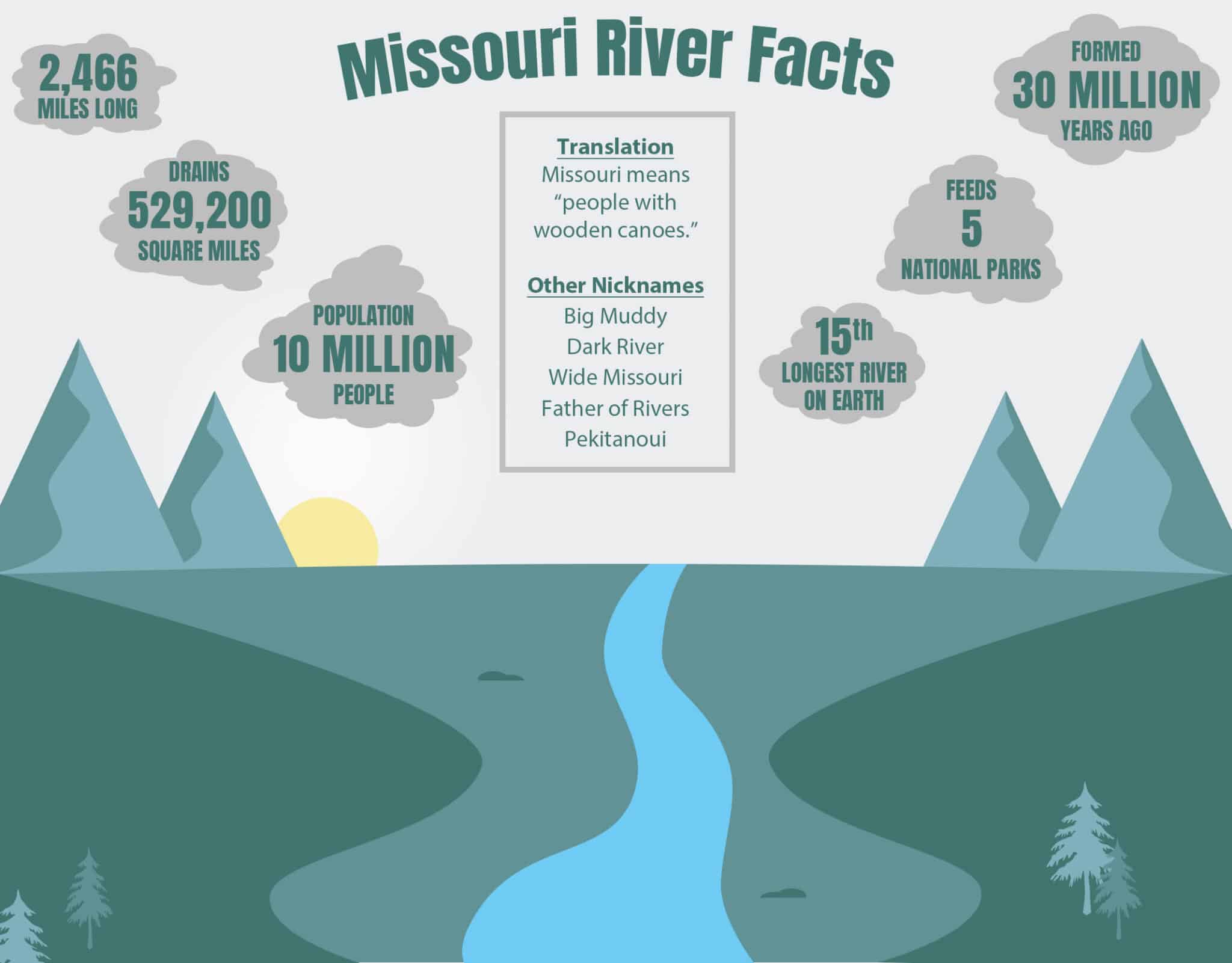

It stretches about 2,341 miles from its headwaters in the Rocky Mountains of Montana all the way to just north of St. Louis. The Mississippi, by comparison, clocks in at roughly 2,320 miles. It’s a narrow margin—about 20 miles depending on who’s doing the measuring—but it counts. This isn't just a geography trivia point; it’s a massive part of how the American West was shaped. The Missouri is the "Big Muddy." It’s a wild, silt-heavy, unpredictable giant that drains about one-sixth of the North American continent.

Geography is messy. Rivers shift. Banks erode. A flood can literally change the length of a river overnight. But as of current U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) data, the Missouri keeps the crown.

The Missouri River vs. The Mississippi: Why Everyone Gets Confused

So why does everyone think the Mississippi is the biggest? It’s mostly about volume and cultural ego. The Mississippi carries way more water. By the time it hits the Gulf of Mexico, it’s a monster. The Missouri, while longer, is often viewed as a "tributary" because it flows into the Mississippi.

Think about that for a second.

You have a river that is physically longer than the one it joins, yet it loses its name the moment they touch. If we were being strictly scientific about "river systems," we’d call the whole thing the Missouri-Mississippi system. That combined stretch would be the fourth-longest river system on Earth, trailing only the Nile, the Amazon, and the Yangtze.

The confusion stems from 19th-century exploration. When Joliet and Marquette were paddling around in 1673, they came from the North. They saw the Mississippi first. To them, the Missouri was just this crazy, muddy influx coming in from the West. By the time Lewis and Clark set out in 1804 to map the longest river in US territory, the naming conventions were already set in stone. We are basically stuck with a naming error from 350 years ago.

✨ Don't miss: Map Kansas City Missouri: What Most People Get Wrong

The Headwaters: Where It All Begins

The Missouri starts at the Three Forks in Montana. This is where the Madison, Jefferson, and Gallatin rivers collide. It’s beautiful. It’s quiet. It doesn't look like a record-breaker there.

But then it picks up steam.

It carves through the "Gates of the Mountains," a name Meriwether Lewis gave to the towering limestone cliffs near Great Falls. From there, it snakes through North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri. It’s a workhorse. It’s not just water; it’s a massive plumbing system for the Great Plains.

How The Longest River In US Was Tamed (Or Not)

The Missouri used to be a shapeshifter. Before the 20th century, it was famous for "snags"—fallen trees hidden just under the surface that would rip the hulls out of steamboats. It was also famous for "avulsion," which is a fancy way of saying the river would decide to jump its banks and start a new path a mile away.

Then came the Pick-Sloan Plan of 1944.

The government decided the longest river in US borders needed to behave. They built six massive dams: Fort Peck, Garrison, Oahe, Big Bend, Fort Randall, and Gavins Point. These created some of the largest reservoirs in the country, like Lake Oahe.

- The Good: These dams stopped the catastrophic flooding that used to wipe out towns. They also provide massive amounts of hydroelectric power and irrigation for farmers who grow the food you probably ate today.

- The Bad: It destroyed the natural ecosystem. The "Big Muddy" isn't as muddy anymore because the silt gets trapped behind the dams. This has been a disaster for native fish like the Pallid Sturgeon, which needs that murky water to survive and spawn.

- The Ugly: The creation of these reservoirs flooded hundreds of thousands of acres of Native American tribal lands. The Standing Rock Sioux and Cheyenne River Sioux tribes lost their best bottomlands, timber, and traditional hunting grounds to the rising waters.

Planning A Trip Along The Missouri

If you actually want to see the Missouri, don't just go to St. Louis. You see the end of it there, but it’s basically just a brown pipe by that point.

🔗 Read more: Leonardo da Vinci Grave: The Messy Truth About Where the Genius Really Lies

Go to the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument in Montana.

This is one of the few places where the river looks exactly like it did when the Corps of Discovery paddled through it in the early 1800s. You can canoe it. You can camp on the banks. There are white sandstone cliffs that look like melting wax. It’s eerie and silent.

Another "must-see" is the Ponca State Park in Nebraska. It’s part of the Missouri National Recreational River. Here, the river is unchannelized. It’s wide, shallow, and full of sandbars. You get a sense of why early explorers were so intimidated by it.

The Logistics Of Measuring A Giant

Measuring a river is surprisingly hard. Do you measure the center of the channel? The thalweg (the deepest part)? Does the length include the twists and turns or a straight line?

The USGS uses high-resolution digital mapping now, but even that is a snapshot in time. In the 1940s, the Missouri was actually much longer—closer to 2,500 miles. But the Army Corps of Engineers "straightened" it for navigation. By cutting off the meanders (the big loops), they essentially shortened the longest river in US history by over 150 miles.

It’s a shorter, faster, more efficient river now. But it lost some of its soul in the process.

Real-World Impact: More Than Just Water

The Missouri River basin supports about 15 million people. If you live in Omaha, Kansas City, or Bismarck, your tap water likely comes from this river. It’s also a corridor for commerce, though not as much as the Mississippi. Barges carry grain and fertilizer, but the "Big Muddy" is notoriously difficult to navigate compared to its eastern cousin.

💡 You might also like: Johnny's Reef on City Island: What People Get Wrong About the Bronx’s Iconic Seafood Spot

The river also acts as a massive "flyway." Millions of migratory birds use the Missouri as a landmark and a rest stop during their north-south travels. If the river dries up or becomes too polluted, the entire bird population of the Central United States takes a hit.

Challenges Facing the River Today

Climate change is hitting the Missouri hard. The river relies on the "snowpack" in the Rockies. If the mountains don't get enough snow, the river runs low. Conversely, if the snow melts too fast in the spring, you get "bomb cyclones" and massive flooding like we saw in 2019.

In 2019, the flooding was so bad it breached dozens of levees and stayed above flood stage for months. It cost billions in damages. It turns out that even with six massive dams, you can't totally control the longest river in US territory. Nature eventually wins.

Actions You Should Take To Experience The Missouri

If you're interested in geography or just want a great American road trip, here is how you should approach the Missouri:

- Visit the Headwaters State Park in Montana. It’s where the three rivers meet to form the Missouri. It’s a spiritual experience for any history nerd.

- Drive the Loess Hills Scenic Byway. This runs along the river valley in Iowa. The hills are made of wind-blown silt from the river's ancient past.

- Check the USGS Water Data. Before you go fishing or boating, look at the real-time flow rates. The Missouri can go from a lazy stream to a terrifying torrent in a matter of hours.

- Support Local Conservation. Groups like Missouri River Relief organize massive trash cleanups. They’ve pulled thousands of tires and tons of plastic out of the water.

The Missouri River is the underdog of American geography. It’s longer than the Mississippi, tougher to navigate, and arguably more important to the expansion of the West. It isn't just a line on a map; it's a living, breathing, and sometimes dangerous part of the American landscape.

Stop calling the Mississippi the longest. Give the "Big Muddy" its due. It earned it over 2,341 grueling miles.