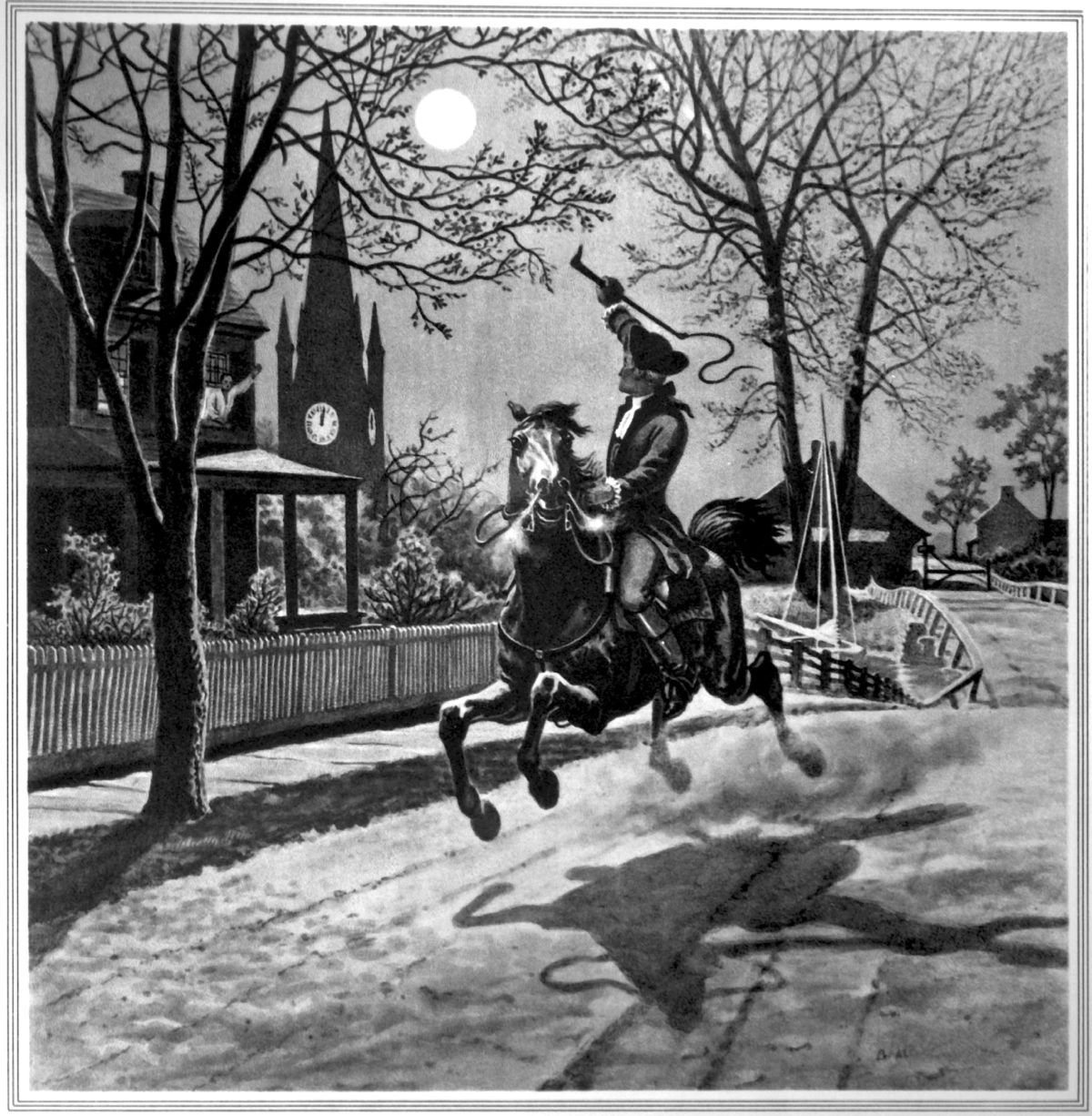

Most of what you think you know about the midnight ride of Paul Revere is probably a lie. Or, at the very least, it's a heavily polished version of the truth written nearly a century after the fact. We can thank Henry Wadsworth Longfellow for that. His 1860 poem turned a chaotic, multi-man intelligence operation into a lonely, heroic sprint. It’s a great story. It just isn't exactly what happened.

History is messy.

On the night of April 18, 1775, Revere wasn't acting as a lone wolf screaming through the streets of Lexington. He was a cog in a very sophisticated—for the time—underground courier system. He was a professional. He was also a middle-aged silversmith with a large family who probably didn't want to get hanged for treason. But duty called.

The Actual Mechanics of the Midnight Ride of Paul Revere

To understand why he rode, you have to understand the tension in Boston. The city was a pressure cooker. British General Thomas Gage had orders to seize rebel stores of gunpowder and arrest Samuel Adams and John Hancock. Everyone knew something was coming. They just didn't know how the British would move.

Revere had spent years building a network. He was a "messenger" for the Massachusetts Committee of Safety. This wasn't some spur-of-the-moment hobby.

When Dr. Joseph Warren summoned Revere around 10:00 PM, the plan was already in motion. Revere had already arranged the famous "one if by land, two if by sea" signal with the sexton of the Old North Church. This wasn't for Revere to see; it was a backup for people in Charlestown in case Revere got caught before he could even leave Boston.

He almost didn't make it out.

Two British officers were patrolling the waters. Revere had to be rowed across the Charles River, right past the HMS Somerset, a massive British man-of-war. Legend says his oars were muffled using a woman's flannel petticoat. Whether that's true or just local flavor, he made it to the other side. He borrowed a horse from John Larkin—a "strong, heavy" horse named Brown Beauty—and began the midnight ride of Paul Revere.

💡 You might also like: Virgo Love Horoscope for Today and Tomorrow: Why You Need to Stop Fixing People

It Wasn't Just One Man

Here is where the narrative usually gets it wrong. Revere wasn't the only one out there.

William Dawes was also sent. Dawes took the longer land route over the Boston Neck. If Revere was caught, Dawes was the insurance policy. They both had the same goal: get to Lexington and warn Adams and Hancock.

Revere reached Lexington around midnight. He didn't yell "The British are coming!" That would have been confusing. Everyone in the colonies considered themselves British at that point. Instead, he likely said "The Regulars are coming out" or "The King's troops are on the march." He was discreet. He was trying to avoid the numerous British patrols scattered along the roads.

After warning the rebel leaders, Revere and Dawes met a third rider: Samuel Prescott. Prescott is the real unsung hero of the midnight ride of Paul Revere.

The Capture Nobody Mentions

The three men rode toward Concord to warn the town that their supplies were at risk. They didn't make it together.

Near Lincoln, they were jumped by a British patrol. Prescott jumped a stone wall and made it all the way to Concord. He's the one who actually finished the mission. Dawes got chased, fell off his horse, and had to walk back to Lexington.

And Revere? He got captured.

📖 Related: Lo que nadie te dice sobre la moda verano 2025 mujer y por qué tu armario va a cambiar por completo

He was held at gunpoint. A British officer reportedly put a pistol to his head and threatened to "blow his brains out" if he didn't tell the truth. Revere, being incredibly bold (or just exhausted), told the officers exactly who he was and that 500 colonial militia were waiting for them. It was a bluff, mostly. But it worked.

The British heard gunfire in the distance—the militia's "alarm" shots—and got nervous. They took Revere’s horse, left him on the side of the road, and rode off to join their main body of troops. Revere had to walk back to Lexington. He actually ended up helping John Hancock’s secretary carry a heavy trunk of papers away from the fighting just as the first shots were fired on Lexington Green.

Why We Remember Revere Instead of Prescott

If Prescott finished the ride and Revere got caught, why do we have statues of the guy who lost his horse?

Marketing.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote "Paul Revere’s Ride" in 1860, right as the American Civil War was looming. He needed a poem that would spark a sense of national unity and Northern grit. "Revere" rhymes with a lot of things. "Prescott" does not. Longfellow took the facts and stretched them until they fit a poetic meter.

It worked. Revere became a legend, and the others became footnotes.

But Revere deserves the credit for the system. He didn't just ride; he organized. He was the one who ensured the lanterns were hung. He was the one who ensured that even if he died, the message would live. That’s real leadership.

👉 See also: Free Women Looking for Older Men: What Most People Get Wrong About Age-Gap Dating

The Significance of the "Alarm and Muster" System

The midnight ride of Paul Revere was successful because of the "alarm and muster" system. This wasn't just a guy on a horse; it was a physical network of bells, drums, and secondary riders.

By the time the British reached Lexington at dawn, the "secret" expedition was the worst-kept secret in New England. Thousands of men were grabbing their muskets because the network Revere helped build worked perfectly.

- The Signal: The lanterns in the Old North Church steeple were only lit for a few minutes.

- The Speed: Revere covered roughly 12-13 miles in about 90 minutes.

- The Geography: He avoided the main roads where patrols were likely to be, sticking to the "back" ways through Medford.

How to Experience the History Today

If you're interested in the real story, you can actually trace the path. Most people just look at the statues, but the geography tells the real tale.

- Visit the Paul Revere House: It’s in Boston’s North End. It’s the oldest remaining structure in downtown Boston. You can see exactly how a silversmith lived. It’s small, cramped, and real.

- The Old North Church: Go inside. Look up. Imagine the sexton, Robert Newman, climbing those wooden stairs in total darkness while British soldiers patrolled the street outside.

- The Battle Road Trail: This is part of the Minute Man National Historical Park. You can walk the actual stretch of road where Revere was captured. Standing there in the woods makes the "midnight" part of the ride feel a lot more intimidating.

Honestly, the best way to understand the midnight ride of Paul Revere is to forget the poem. Stop imagining a guy in a cape shouting at windows. Imagine a nervous, middle-aged businessman sneaking past a massive warship in a rowboat, desperate to save his friends and his country from a fight he knew was coming.

The truth is much more impressive than the myth.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you want to dive deeper into the technicalities of the American Revolution's intelligence networks, start with primary sources. Read Revere's own 1798 letter to Jeremy Belknap, where he recounts the night in his own words. It's far more grounded than any textbook.

You should also look into the role of Margaret Kemble Gage. She was the American-born wife of the British General, and many historians believe she was the "confidential source" who leaked the British plans to Dr. Warren in the first place.

History isn't just a list of dates. It's a series of choices made by people who didn't know how the story was going to end. Revere didn't know he'd become a legend. He just knew he had a horse and a message.