If you’re looking for a simple date, most history books will point you straight to March 10, 1876. That's the day Alexander Graham Bell supposedly shouted at his assistant through a liquid transmitter. But honestly, the question of when was the first telephone made is a massive headache for historians because "first" is a loaded word. Was it the first time someone thought of it? The first working prototype? Or the first time a lawyer got to the patent office?

History is messy.

Bell usually gets all the credit, but he wasn't working in a vacuum. There were half a dozen guys in the mid-1800s trying to figure out how to shove a human voice through a copper wire. If you define a telephone as a device that transmits speech-like sounds, you could argue it happened decades before Bell ever picked up a receiver. If you mean a commercially viable product, that's a different story entirely.

The 1876 Patent Race That Changed Everything

Most people remember 1876 as the year. It’s the year of the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia where the world first saw what this thing could do. But the real drama happened on February 14, 1876.

That morning, Bell’s lawyer filed a patent application for the telephone. Just a few hours later—literally around noon—a guy named Elisha Gray showed up at the same office to file a "caveat," which is basically a legal placeholder saying, "Hey, I’m working on this invention too." Because Bell’s paperwork was processed first, he won the legal rights to one of the most profitable patents in human history.

It was a photo finish.

Wait, it gets weirder. Bell’s early designs actually used a "liquid transmitter" method that looked suspiciously like the one Gray described in his caveat. People have been arguing for over a century about whether Bell peeked at Gray’s notes. Regardless of the gossip, the official record states that the first telephone made into a functional, patented reality belongs to Bell in the spring of 1876.

"Mr. Watson, Come Here"

We’ve all heard the quote. Bell knocked over some acid, or maybe he just wanted to test the line, and he called out to Thomas Watson. It worked. But that device was a far cry from the sleek iPhones we carry today. It was a bulky, vibrating mess of wires and parchment. It didn't even have a ringer. If you wanted to call someone, you basically had to shout or whistle into the thing and hope they were standing on the other end.

The Forgotten Pioneers Before Bell

To really understand when was the first telephone made, we have to look back at Antonio Meucci.

🔗 Read more: Why a 9 digit zip lookup actually saves you money (and headaches)

Meucci was an Italian immigrant living in Staten Island. Way back in 1849, he allegedly developed a form of voice communication to connect his basement laboratory to his wife’s bedroom on the second floor because she suffered from chronic arthritis. He called it the "teletrofono."

The guy was brilliant but broke.

He couldn't afford the $250 fee for a permanent patent. Instead, he filed a temporary notice in 1871. When it came time to renew it in 1874, he didn't have the ten bucks. Two years later, Bell gets the patent. In 2002, the U.S. House of Representatives actually passed a resolution (H.Res. 269) acknowledging Meucci’s work, essentially admitting that if he’d had the money to keep his patent active, Bell might never have gotten his.

Johann Philipp Reis and the "Telephon"

Then there’s Johann Philipp Reis. In 1861, this German physicist built a device that could transmit musical notes and even some blurry speech. He actually coined the term "telephon." His machine used a "make-and-break" circuit, which meant it was great at transmitting a steady hum or a melody, but it struggled with the complex, varying frequencies of the human voice.

It was a telephone in name, but not quite in function. It was more like a very temperamental musical instrument that lived in a lab.

Why 1876 Is the Date That Stuck

Why do we ignore the 1840s and 1860s and settle on 1876? It’s because of the "harmonic telegraph."

In the 1870s, the big tech problem wasn't talking; it was telegrams. Western Union was the Google of its day. They wanted a way to send multiple telegraph messages over a single wire at the same time. Bell was trying to solve this by using different musical pitches.

During his experiments, he realized that if he could transmit a continuous wave instead of just "on and off" pulses, he could replicate the vibrations of a voice. This was the "Aha!" moment.

💡 You might also like: Why the time on Fitbit is wrong and how to actually fix it

- June 1875: Bell and Watson manage to transmit a "twang" sound.

- March 1876: The first clear sentence is transmitted.

- August 1876: The first long-distance call (about 8 miles) happens in Ontario, Canada.

It wasn't just about making the device; it was about proving it could work over distances. By the end of 1876, the world knew that life was about to get a lot louder.

The Tech Inside the First Phones

If you opened up one of these early machines, you wouldn't find a microchip. You’d find a diaphragm, a magnet, and a coil of wire.

Basically, when you talk, your voice creates sound waves. Those waves hit a thin membrane (the diaphragm), making it vibrate. In Bell’s design, this membrane was attached to a piece of iron near an electromagnet. As the iron moved, it changed the magnetic field, creating a varying electrical current. That current traveled down the wire to the other end, where another magnet and diaphragm turned the electricity back into sound.

It’s elegant. Simple. And remarkably close to how some analog speakers still work today.

However, the "liquid transmitter" Bell used for his first famous call was different. It involved a needle dipping into a cup of sulfuric acid and water. As the diaphragm vibrated, the needle moved up and down in the liquid, changing the electrical resistance. It was messy, dangerous, and definitely not something you’d want on your kitchen counter. Thankfully, they moved away from the acid pretty quickly.

Expanding the Network: 1877 and Beyond

Once the question of when was the first telephone made was settled in the eyes of the law, the race to build the network began.

The first commercial telephone line was established in 1877 between Boston and Somerville, Massachusetts. It wasn't a "network" like we think of it. It was just a wire connecting two specific locations. If you wanted to talk to three different people, you needed three different wires and three different phones.

Imagine your wall covered in wooden boxes just to talk to your neighbors.

📖 Related: Why Backgrounds Blue and Black are Taking Over Our Digital Screens

The invention of the switchboard in 1878 changed that. Suddenly, you only needed one wire going to a central office where an operator (usually a woman, because teenage boys were too rude and kept pranking callers) would manually plug your wire into the person you wanted to reach.

Common Misconceptions About the Telephone’s Origin

We like to think of inventors as lone geniuses working in garages. That’s rarely how it happens.

- Bell didn't invent the "telephone" out of thin air. He was building on the work of Michael Faraday and Joseph Henry, who mastered electromagnetism decades earlier.

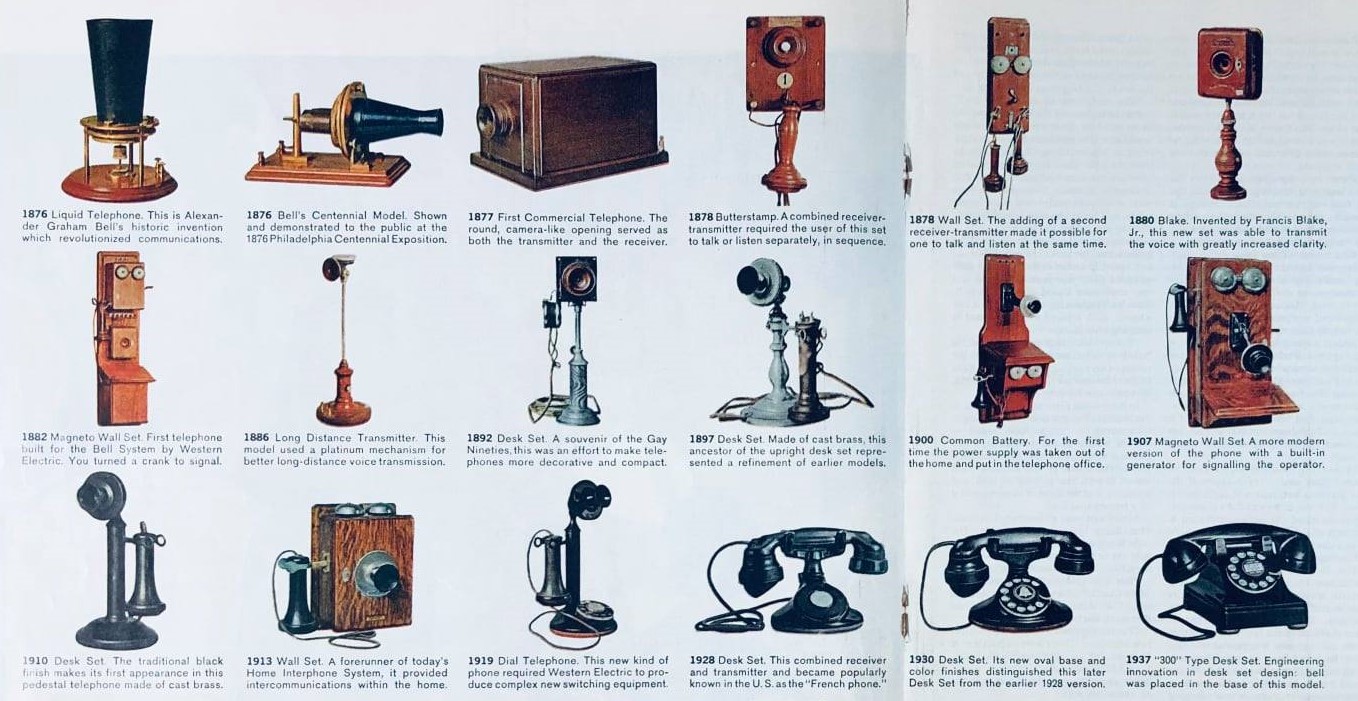

- The first phones didn't have dials. Dials didn't show up until the 1890s. Early phones were "crank" phones. You turned a handle to generate enough electricity to ring the operator's bell.

- It wasn't an instant success. Many people thought the telephone was a toy. Even the President of Western Union supposedly turned down the chance to buy Bell's patent for $100,000, calling the device an "idiot's toy." That might be the biggest business blunder in history.

The Global Perspective

While America was obsessed with Bell and Gray, other countries were doing their own thing.

In Hungary, Tivadar Puskás was dreaming up the telephone exchange. In France, they were experimenting with "theatrophones," where you could pay to listen to a live opera performance over the phone lines. This was basically the first version of live streaming, happening in the 1880s!

The telephone wasn't just an American invention; it was a global obsession. Everyone realized simultaneously that the world was about to get much smaller.

Practical Takeaways from the History of the Phone

Understanding the origins of the telephone isn't just for trivia night. It teaches us a lot about how innovation actually works.

- Timing is everything: Meucci had the tech but not the money. Gray had the tech but was a few hours late. Bell had the tech and the legal team.

- Iteration wins: The first phone was terrible. It was barely audible and used acid. But it was a starting point.

- Infrastructure matters: The phone was useless until the switchboard and long-distance lines were built.

If you're interested in tracing this history further, your best bet is to look into the Smithsonian Institution’s archives or the Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site in Baddeck, Nova Scotia. They hold the original sketches and prototypes that show the progression from "twanging wire" to "world-changing communication."

The telephone didn't just appear. It was "made" over the course of thirty years by dozens of people, but the 1876 milestone remains the anchor for everything that followed. Next time you pick up your smartphone, remember that it all started with a cup of acid and a guy who got to the patent office before lunch.

To dig deeper into the actual hardware, research the difference between "dynamic" and "variable resistance" transmitters. This is the technical divide that separated the early hobbyist toys from the devices that could actually carry a conversation across a city. Reading the original 1876 patent (U.S. Patent 174,465) is also a fascinating look into how Bell described a technology that he barely understood himself at the time.

Next Steps for History Buffs:

- Check out the "Reis Telephone" at the National Museum of American History website to see why it almost worked but didn't quite make the cut.

- Compare the 1876 Bell patent diagrams with the drawings in Elisha Gray’s caveat; the similarities are a great entry point into one of the biggest "what-ifs" in science history.

- Visit a local communications museum if you can; many have original hand-crank magneto phones that still function, giving you a tactile sense of what "calling" meant in the 19th century.