Everyone thinks they know the story. You see the ruby slippers, hear the high notes of "Over the Rainbow," and feel that warm, fuzzy nostalgia for 1939 cinema. But honestly? The making of the Wonderful Wizard of Oz was a total nightmare. It wasn't just "movie magic" happening on a backlot in Culver City; it was a series of near-fatal accidents, frantic director swaps, and a studio system that basically treated its stars like property.

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) wanted a hit. They saw Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs raking in cash in 1937 and decided they needed their own fairy tale. They didn't just want a movie; they wanted a spectacle. They got one, but at a cost that most modern film sets would find absolutely criminal.

Why the Making of the Wonderful Wizard of Oz Was a Logistics Disaster

Technicolor was the big new thing. It was expensive, cumbersome, and required an insane amount of light to actually register on film. Because the cameras needed so much illumination, the sets for the making of the Wonderful Wizard of Oz were often over 100 degrees. Imagine being Bert Lahr, stuffed into a costume made of real lion skins—yes, actual lion pelts—weighing about 90 pounds, while sweating under high-intensity lights. He couldn't even eat in that thing. He was restricted to a liquid diet through a straw because the facial prosthetics were so delicate and took hours to reapply.

It wasn't just the heat. It was the chemicals.

We talk about "safety standards" today, but back then, they were basically nonexistent. The "snow" in the famous poppy field scene? Pure asbestos. The crew literally showered the actors in chrysotile asbestos fibers because it looked fluffy and didn't catch fire under the hot lights. You've got Dorothy, the Scarecrow, and the Tin Man napping in a pile of carcinogens. It’s wild to think about now.

The Aluminum Powder Hospitalization

Buddy Ebsen was the original Tin Man. You probably know him from The Beverly Hillbillies, but he was supposed to be in Oz. Ten days into filming, he couldn't breathe. His lungs were failing. The production had been coating him in silver aluminum powder every day, and the dust eventually coated his lungs, preventing oxygen from getting into his bloodstream. He ended up in an iron lung. MGM didn't wait for him to get better. They just hired Jack Haley, switched to an aluminum paste instead of powder, and didn't even tell Haley why the first guy left.

A Revolving Door of Directors

Most people associate Victor Fleming with the film. He’s the one who got the credit. But the making of the Wonderful Wizard of Oz actually cycled through five different directors. Richard Thorpe was the first, and he lasted about two weeks. The footage he shot made Judy Garland look like a generic doll with a blonde wig and heavy makeup. It didn't work.

George Cukor stepped in briefly. He didn't film a single frame, but he made the most important creative decision of the entire production: he told Judy to be herself. He ditched the wig, toned down the makeup, and told her to act like a girl from Kansas. That's why the performance feels so grounded. After Cukor left to work on Gone with the Wind, Fleming took over and did the bulk of the heavy lifting.

💡 You might also like: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

Then Fleming left to finish Gone with the Wind (because that production was also a mess), and King Vidor stepped in to film the sepia-toned Kansas sequences. It’s a miracle the movie has a cohesive tone at all.

Margaret Hamilton and the Fire

The Wicked Witch of the West almost died on set. During her fiery exit from Munchkinland, a trap door failed to open fast enough. The pyrotechnics went off while she was still standing there. Her copper-based green makeup heated up instantly, causing second and third-degree burns on her face and hands.

She was out for weeks. When she came back, she refused to do any more work with fire. Can you blame her? Her stunt double, Betty Danko, also got injured later on while filming the "Surrender Dorothy" skywriting scene. The "broomstick" (which was actually a smoking pipe) exploded. It was a dangerous place to work.

The Judy Garland Factor

MGM treated Judy Garland like a machine. She was 16 years old, but they wanted her to look younger, so they bound her torso with a painful corset to hide her curves. To keep her working 16-hour days and then keep her thin enough for the camera, the studio allegedly supplied her with "pep pills" (amphetamines) to stay awake and barbiturates to sleep.

It started a lifelong struggle with addiction.

The studio’s control was absolute. They monitored her food, her social life, and her weight. When you watch her sing "Over the Rainbow," you're seeing a performance of pure vulnerability, but behind the scenes, she was under immense pressure from studio head Louis B. Mayer to be the "little girl" he could market to the world.

The Munchkins: Fact vs. Fiction

There’s this long-standing urban legend about the actors who played the Munchkins being wild and rowdy at the Culver Hotel. While some of them definitely enjoyed their time off, many of those stories were exaggerated by Judy Garland herself in later interviews for comedic effect.

📖 Related: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

In reality, most of the 124 little people hired for the film were professional performers. They were paid less than Toto the dog. Toto's trainer was getting $125 a week, while most of the Munchkin actors were making around $50. It’s a glaring example of the era’s inequality.

The Myth of the Hanging Man

If you look at the background of the woods while the trio is walking down the road, some people swear they see a man hanging from a tree.

It’s a bird.

Specifically, it’s an emu or a large crane. The studio had borrowed several exotic birds from the Los Angeles Zoo to make the forest look more "otherworldly." The lighting and the low resolution of early home video releases made the bird's flapping wings look like a body swinging. In the high-definition restorations we have now, it's very clearly a bird.

The Music That Almost Wasn't

"Over the Rainbow" is arguably the most famous song in movie history. But it was almost cut.

Producers thought the Kansas sequence was too long. They felt the song slowed down the pace of the movie. They also thought it was "undignified" for a star like Judy Garland to be singing in a barnyard. It took the persistence of associate producer Arthur Freed and vocal coach Roger Edens to keep it in. Without their pushback, the making of the Wonderful Wizard of Oz would have lacked its emotional anchor.

The "Jitterbug" number didn't have the same luck. It was a high-energy dance sequence that cost $80,000 to film (a fortune in 1939). It was cut because the producers thought it would date the movie too much, as the "jitterbug" was a contemporary fad.

👉 See also: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

Why We Still Care

The film wasn't an immediate massive financial success. It did okay, but because the budget was so astronomical—nearly $3 million—it barely broke even on its first run. It wasn't until the 1956 television broadcast on CBS that it became a cultural phenomenon.

That’s when the world truly fell in love with it.

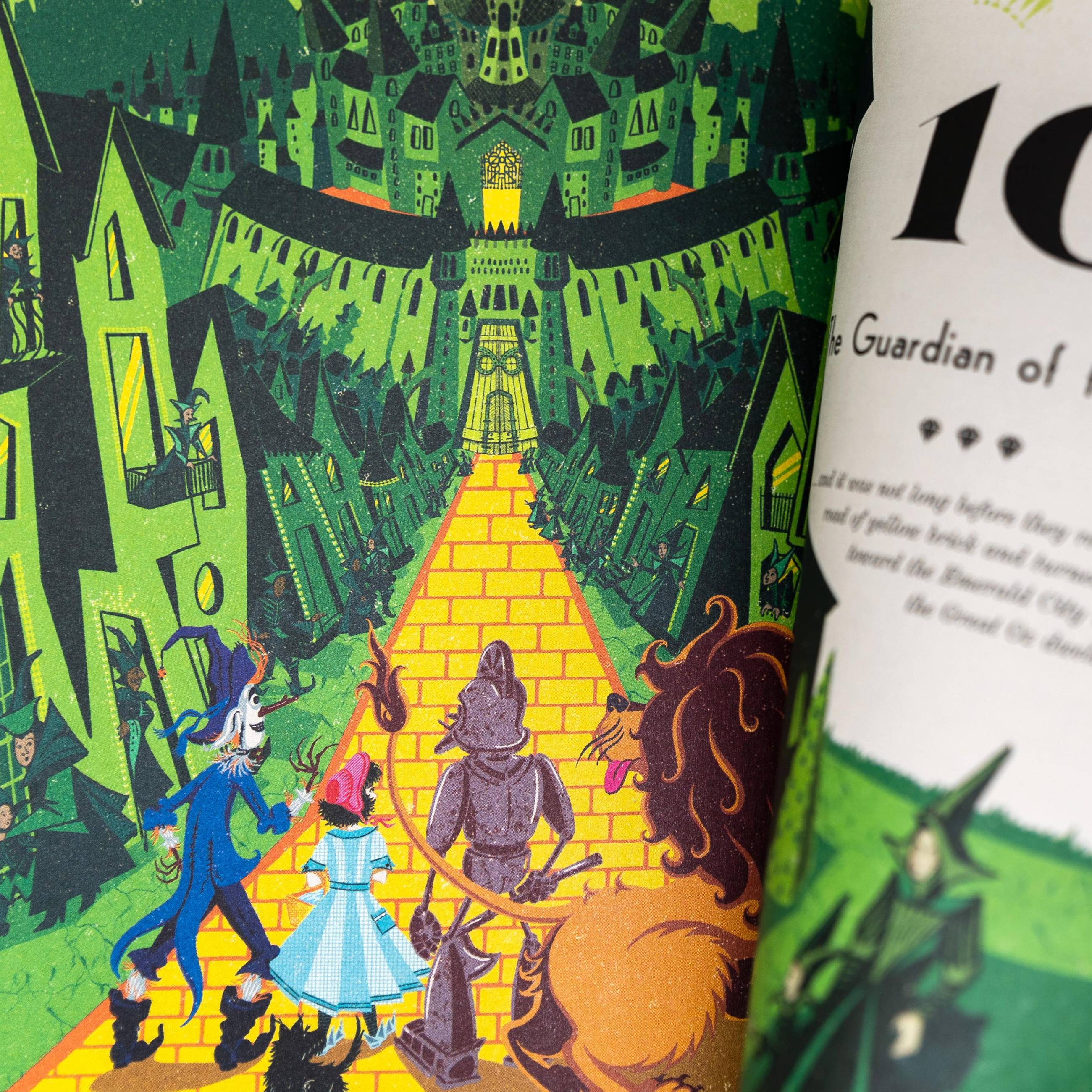

The making of the Wonderful Wizard of Oz serves as a bridge between the old-school Vaudeville era and the high-tech blockbuster era. It used matte paintings, miniature models, and practical effects that still look better than some modern CGI. The "tornado" was actually a 35-foot long muslin sock agitated by a compressed air hose and moved across a miniature Kansas landscape.

It was brilliant engineering born out of necessity.

Actionable Takeaways for Film History Buffs

If you're looking to dive deeper into the history of this production, don't just stick to the movie. There are ways to see the "seams" of how it was built.

- Watch the 4K Restoration: Modern scans show incredible detail in the matte paintings. You can see the brushstrokes on the Emerald City backgrounds, which gives you a real appreciation for the scenic artists.

- Read "The Making of the Wizard of Oz" by Aljean Harmetz: This is widely considered the definitive text on the production. It uses internal MGM memos and interviews to debunk the myths.

- Listen to the Deleted Audio: You can find the full audio and some grainy footage of "The Jitterbug" online. It changes the entire rhythm of the middle of the film.

- Visit the Academy Museum in LA: They often have the original props, including the ruby slippers (one of several pairs), on display. Seeing them in person puts the scale of the production in perspective.

The reality is that The Wizard of Oz is a masterpiece created through a combination of visionary art and systemic exploitation. Understanding both sides doesn't ruin the movie; it makes the fact that it exists at all even more incredible.