Terms change. Language evolves. If you grew up in the nineties, you probably remember the phrase "Third World" being tossed around like it was an objective fact. It wasn't. It was a cold war relic that eventually felt... well, pretty insulting. So, we shifted. We started talking about the meaning of developing countries as a way to describe nations that are basically "works in progress" regarding their economy and quality of life. But honestly? It’s complicated. It’s not just about a low GDP or lack of paved roads. It’s a messy, moving target that involves everything from infant mortality rates to how many people can actually access a stable internet connection.

Defining it is tricky. There is no single, globally agreed-upon checkbox that makes a country "developing." Organizations like the World Bank, the IMF, and the UN all have their own yardsticks. Some look strictly at the money—the Gross National Income (GNI) per capita. Others, like the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), care more about the Human Development Index (HDI), which looks at how long people live and how much schooling they get. It's the difference between looking at a person's bank account versus looking at their actual health and happiness.

The Real Meaning of Developing Countries in a Global Economy

Most people assume the meaning of developing countries is just "poor." That’s a massive oversimplification. Take a look at the "BRICS" nations—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. For decades, these were the poster children for developing economies. Now? China is the world's second-largest economy. India is a global tech hub. Yet, they often still fall under the "developing" umbrella in certain international agreements because their per capita wealth is still lower than that of the US or Norway.

It’s about the gap. A developing country usually has a huge disparity between the urban elite and the rural poor. You might see a gleaming skyscraper in Jakarta right next to a settlement that lacks basic sanitation. That contrast is the hallmark of development. It is the transition from an economy based on farming and raw materials to one based on industry, services, and technology.

💡 You might also like: US Dollar 1 in Nepal: Why the Exchange Rate is Doing Weird Things Right Now

The Money Side: How the World Bank Divides Us

The World Bank keeps it simple. Maybe too simple. They use GNI per capita to sort countries into four groups: Low income, Lower-middle income, Upper-middle income, and High income.

As of the latest 2024-2025 thresholds, if a country has a GNI per capita of $1,145 or less, it’s low income. If it’s over $14,005, it’s high income. Everyone in the middle? Developing. But this creates weird scenarios. You have countries that are technically "high income" but lack the social infrastructure or political stability of an "advanced" nation. This is why economists are moving away from these rigid labels. Even the World Bank stopped using "developing" and "developed" in its main data reports back in 2016, though the terms still haunt every news article and political debate.

Why the Labels are Actually Controversial

Labels have consequences. This isn't just semantics. When a country is labeled "developing," it might get better trade deals or lower interest rates on international loans. Organizations like the World Trade Organization (WTO) actually let members self-designate as developing. This causes huge fights.

South Korea, for example, long maintained its developing status at the WTO to protect its agriculture sector, despite being home to Samsung and Hyundai. They finally gave it up in 2019 under pressure. China still claims developing status in many arenas. Why? Because it gives them "special and differential treatment." If you're a giant economy but still have millions of people living in poverty, where do you draw the line? It's a political tug-of-war.

The Human Factor: Beyond the Dollar Sign

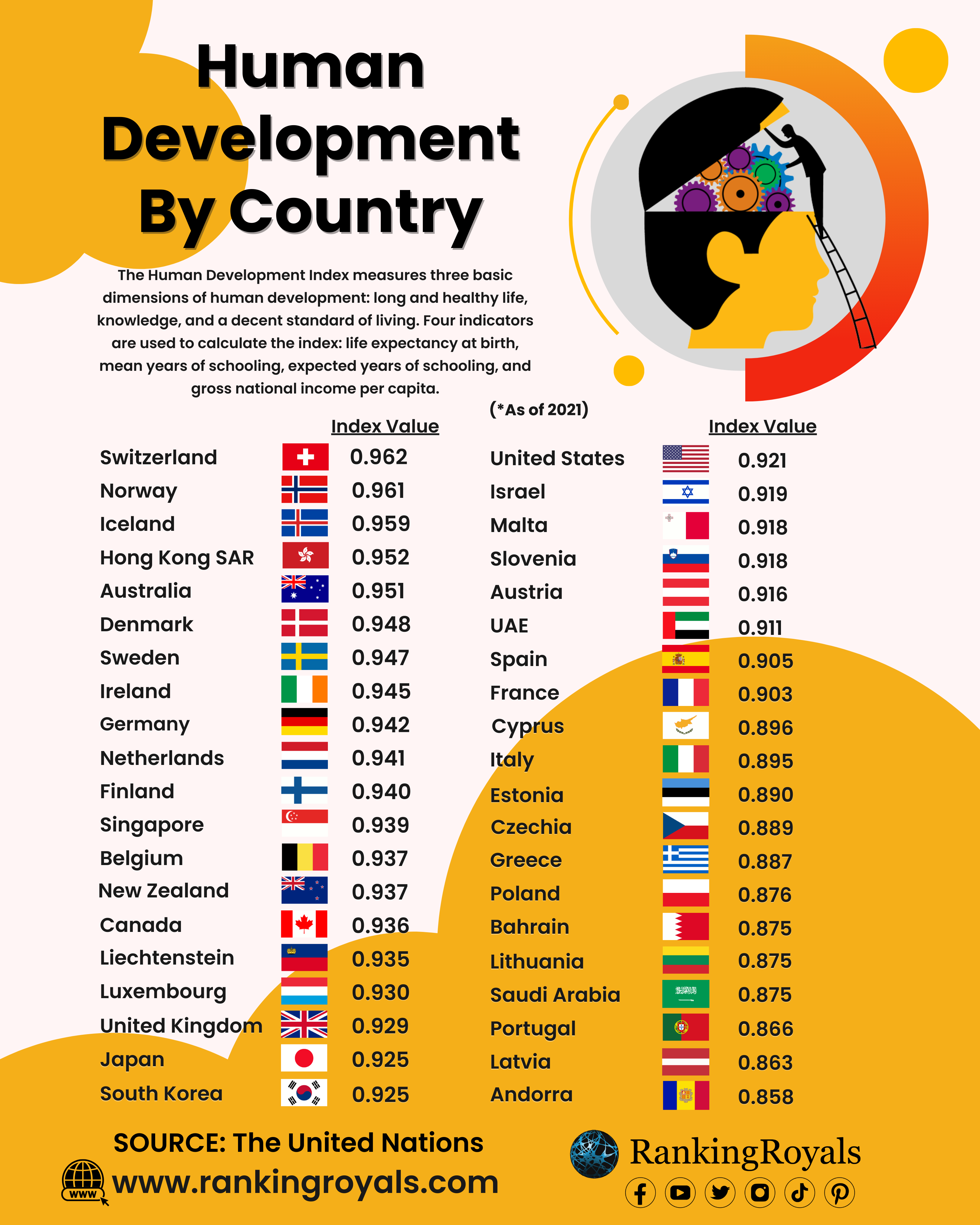

We need to talk about the Human Development Index (HDI). This is the UN's way of saying "money isn't everything."

A country could have a lot of oil wealth but terrible schools and no freedom of the press. Is that developed? Probably not. The HDI looks at life expectancy, years of schooling, and standard of living. This gives us a much clearer picture of the meaning of developing countries on the ground. You see countries like Cuba or Sri Lanka that sometimes punch above their weight in health and education relative to their actual wealth.

🔗 Read more: Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Ltd: Why the World’s Biggest Bank is Moving Differently Now

On the flip side, you have nations with high GDP growth that are failing their citizens in terms of basic safety or environmental protection. Growth is not development. Growth is just more stuff; development is better lives.

Life on the Ground in a Developing Economy

What does it actually look like? It looks like potential. It looks like a massive youth population. In many developing nations in Africa and Southeast Asia, the median age is under 20. That is a "demographic dividend" if there are jobs, but a "demographic time bomb" if there aren't.

Infrastructure is usually the big bottleneck. We're talking about "last mile" connectivity. Can a farmer get his crops to the city before they rot? Is the electricity stable enough to run a factory? In many places, people have "leapfrogged" over old tech. They skipped landline phones and went straight to mobile banking. In Kenya, M-Pesa changed the world before Venmo was even a thing. That’s the irony of development—sometimes the lack of old systems makes room for the newest ones.

The Sustainability Problem

Here is the hard truth: the way the "developed" world got rich—burning coal, exploiting resources—isn't an option anymore. Or at least, it shouldn't be.

Developing countries are now caught in a vice. They are told to grow their economies to lift people out of poverty, but they are also told to do it without the cheap, dirty energy the West used for 200 years. This is the core of "Climate Justice." Many developing nations argue that they shouldn't have to pay for a problem they didn't create. It's a fair point. If you’re a leader in a developing nation, do you provide electricity to a million homes using coal, or do you wait for expensive green tech while your people sit in the dark?

Misconceptions That Just Won't Die

People think "developing" means "stagnant." It’s usually the opposite. Developing countries often have much higher growth rates than developed ones. While the US or UK might be happy with 2% growth, a developing nation might be hitting 7% or 8%.

Another myth? That they all need "saving" by Western aid.

While aid matters, trade and domestic policy matter way more. Most development happens because of internal reforms, local entrepreneurship, and regional trade. Foreign aid is often a drop in the bucket compared to "remittances"—money sent home by workers living abroad. In countries like Nepal or the Philippines, remittances are a huge chunk of the total economy.

✨ Don't miss: Precio del dólar hoy en Tijuana: Por qué cambia tanto de una calle a otra

Shifting Toward "Global South"

You might have noticed the term "Global South" popping up lately. It’s the new preferred phrase in academic and diplomatic circles. It’s less about "developing" (which implies a linear path toward being exactly like the West) and more about a shared history of colonialism and a shared position in the global power structure.

The meaning of developing countries is shifting from a description of poverty to a description of power dynamics. It’s about who gets a seat at the table. When the G20 meets, the "developing" members are increasingly the ones driving the conversation because that’s where the customers, the workers, and the resources are.

What This Means for Business and You

If you’re an investor or a business owner, "developing" is where the action is. The "developed" world is aging. It’s shrinking in some places. The future of global consumption is in the developing world.

But it’s risky.

Currency volatility, political shifts, and legal systems that aren't always predictable make it a gamble. However, the companies that figured out how to operate in these markets—think Unilever or Coca-Cola—have built massive empires there. They didn't wait for these countries to "arrive" at developed status; they met them where they were.

Actionable Steps for Navigating Development Trends

- Stop using "Third World." It’s outdated and factually incorrect. Stick to "Developing Economies" or "Global South" depending on the context.

- Look at the HDI, not just GDP. If you are analyzing a market or a country's stability, check the UNDP’s Human Development Reports. A country with rising wealth but falling education is a red flag for long-term stability.

- Watch the "Middle-Income Trap." This is when a country gets to a certain level of wealth but can't break through to "high income" because its wages are too high for cheap manufacturing but its innovation isn't strong enough for high-tech. Keep an eye on countries like Thailand or Turkey for this.

- Monitor demographic shifts. Investigate the "median age" of countries you are interested in. A young population is a massive labor force and consumer base for the next 40 years.

- Diversify your sources. Don't just read Western financial news. Check out outlets like Al Jazeera, The South China Morning Post, or African Business to get a perspective from the ground.

The world isn't divided into "rich" and "poor" anymore. It’s a spectrum. The meaning of developing countries is ultimately about a journey. Some are sprinting, some are stumbling, but almost all of them are moving. Understanding that nuance is the difference between a smart global citizen and someone stuck in a 1980s textbook.