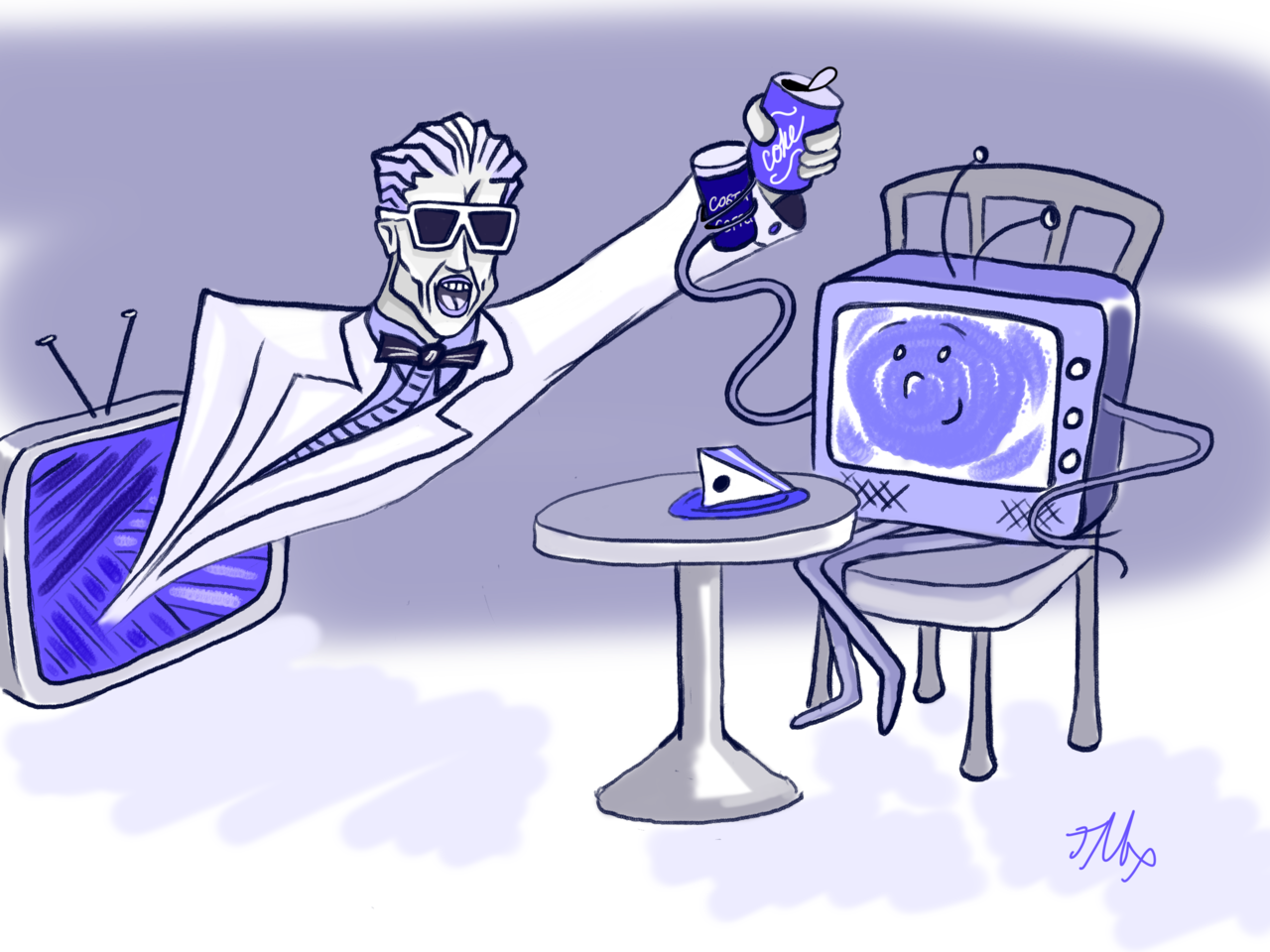

Chicago. November 22, 1987. A quiet Sunday night. Most people were glued to the TV, probably watching the news or caught up in an episode of Doctor Who. Then the screen flickered. A man in a plastic mask—the grin of 1980s digital icon Max Headroom—stared back at thousands of confused viewers. He didn't say anything at first. He just swayed, hissed, and laughed while a sheet of corrugated metal buzzed in the background.

It was weird.

Actually, it was terrifying. This wasn't a glitch. It was a high-tech hijacking, and decades later, the Max Headroom broadcast signal intrusion remains the most famous unsolved mystery in the history of television.

The Night the Airwaves Broke

The first hit happened during the 9:00 PM news on WGN-TV. Sportscaster Dan Roan was right in the middle of talking about the Chicago Bears when the screen went black. When the image returned, it wasn't Roan. It was a distorted figure wearing that signature latex mask and sunglasses. The signal lasted only about 25 seconds before WGN engineers managed to switch the frequency of their studio-to-transmitter link.

Roan's reaction? "Well, if you're wondering what happened, so am I."

But the hackers weren't done. About two hours later, during a broadcast of the Doctor Who serial "Horror of Fang Rock" on WTTW, they struck again. This time, they had audio. For 90 seconds, the intruder moaned, hummed the Mission: Impossible theme, yelled about "New Coke," and held up a middle finger encased in a rubber hollowed-out dildo. It ended with a woman hitting the figure's bare buttocks with a flyswatter.

Then, just as quickly as it started, the signal cut back to the Doctor.

🔗 Read more: Why the Star Trek Flip Phone Still Defines How We Think About Gadgets

How Did They Actually Do It?

You’ve gotta understand that in 1987, this wasn't just some kid with a laptop. There were no laptops. This required serious gear and even more serious guts. To pull off the Max Headroom broadcast signal intrusion, the perpetrators had to physically position themselves somewhere with a line of sight to the stations' receiver towers—specifically the ones atop the Sears Tower and the John Hancock Center.

Basically, they used a "path" intrusion.

By using a high-gain antenna and a powerful microwave transmitter, they overpowered the legitimate signal being sent from the TV studio to the broadcast tower. Think of it like a megaphone. If the studio is talking to the tower through a megaphone, the hacker just showed up with a bigger, louder megaphone and pointed it directly at the tower's ear. The tower, unable to tell the difference, simply broadcasted whatever signal was stronger.

WTTW didn't have engineers on duty at their transmitter site at the time. They were at the studio, watching helplessly. By the time anyone could have reacted, the prank was over.

The Investigation That Hit a Brick Wall

The FCC went into full-blown panic mode. This wasn't just a prank; it was a federal felony. If someone could hijack a local news broadcast, what stopped them from hijacking a presidential address or a civil defense alert?

Investigators, led by FCC veteran Raymond Stranski, scoured the Chicago area. They looked into "video pirates" and ham radio enthusiasts. They checked the "corrugated metal" background, which some thought looked like a piece of siding from a warehouse. Rumors flew. Some thought it was a disgruntled ex-employee. Others pointed toward the underground "phreaker" community—the proto-hackers of the 80s who obsessed over phone lines and airwaves.

💡 You might also like: Meta Quest 3 Bundle: What Most People Get Wrong

The most popular theory for years focused on a specific pair of brothers from the Chicago suburbs, often referred to in Reddit sleuthing circles as "J" and "K." The theory suggests they were part of a niche experimental music and tech scene. People claimed the humor matched their style. They had the equipment. They lived in the right area.

But there’s no "smoking gun." No one confessed. No physical evidence was ever recovered. The FCC eventually stopped active pursuit of the case because, honestly, what could they do? The trail had gone cold before the 80s were even over.

Why This Specific Intrusion Changed Television Forever

Before this happened, broadcast security was largely built on trust and the sheer cost of equipment. After the Max Headroom broadcast signal intrusion, the industry had to wake up. It exposed a massive vulnerability in how "STL" (Studio-to-Transmitter Link) signals were handled.

Modern digital broadcasting is encrypted and much harder to "jam" in this specific way. Today, a hacker is more likely to compromise a station's social media account or an internet-connected playback server than they are to point a microwave dish at a skyscraper.

The 1987 incident was the "Last Hurrah" of the analog pirate. It was a moment where the technology was just accessible enough for a smart hobbyist to break, but the laws and security measures weren't yet ready to stop them.

Misconceptions You’ve Probably Heard

People often get a few things wrong about that night.

📖 Related: Is Duo Dead? The Truth About Google’s Messy App Mergers

- "It was a live puppet." Nope. It was just a guy in a mask. The mask was a mass-produced "Max Headroom" costume piece you could buy at the time.

- "They caught the guy." No, they didn't. There are plenty of YouTube videos claiming to have "unmasked" the hacker, but it's all speculation.

- "It only happened once." As mentioned, it happened twice in one night. The first was a "dry run" on WGN; the second was the "full performance" on WTTW.

The audio from the WTTW clip is also incredibly difficult to understand because of the distortion. He mentions Chuck Swirsky (a Chicago sportscaster), "Clutch Cargo" (a 1950s cartoon), and complains about his piles (hemorrhoids). It was a chaotic, stream-of-consciousness rant that feels more like an "anti-art" performance than a political statement.

What This Means for Today’s Tech

We live in an age of deepfakes and sophisticated cyber warfare. Looking back at the Max Headroom broadcast signal intrusion feels quaint, but the core lesson remains: if there is a signal, someone will try to hijack it.

The event has moved into the realm of folklore. It’s been referenced in movies, inspired creepypastas, and remains a staple of "Unsolved Mysteries" forums. It represents a brief window in time where a person could become a ghost in the machine and disappear without a trace.

If you’re interested in exploring the technical side of this, or if you’re a history buff who loves a good cold case, there are a few things you can do to get the full picture.

How to Dive Deeper into the Mystery

- Watch the raw footage: Search for the WTTW "Horror of Fang Rock" intrusion on archival sites. Pay attention to the background—the "swaying" motion is actually the camera moving, not the actor.

- Read the FCC reports: While many are still classified or redacted, FOIA requests over the years have shed light on the initial "Panic" at the FCC's Central Region office.

- Explore the "SubGenius" connection: Many theorists believe the humor in the video aligns with the Church of the SubGenius, a parody religion popular in the 80s tech underground. Look into the "Slack" philosophy to see if you can spot the tonal similarities.

- Audit your own security: If you work in media or IT, use this as a case study in "Single Point of Failure." The hacker succeeded because the link between the studio and the tower was unencrypted and unprotected.

The Max Headroom hacker is likely in their 60s or 70s now. They might be your neighbor. They might be a retired engineer living in a quiet Chicago suburb, laughing every time a new documentary about that night pops up on their smart TV. We may never know their name, but their 90 seconds of fame changed the way we look at the screen forever.