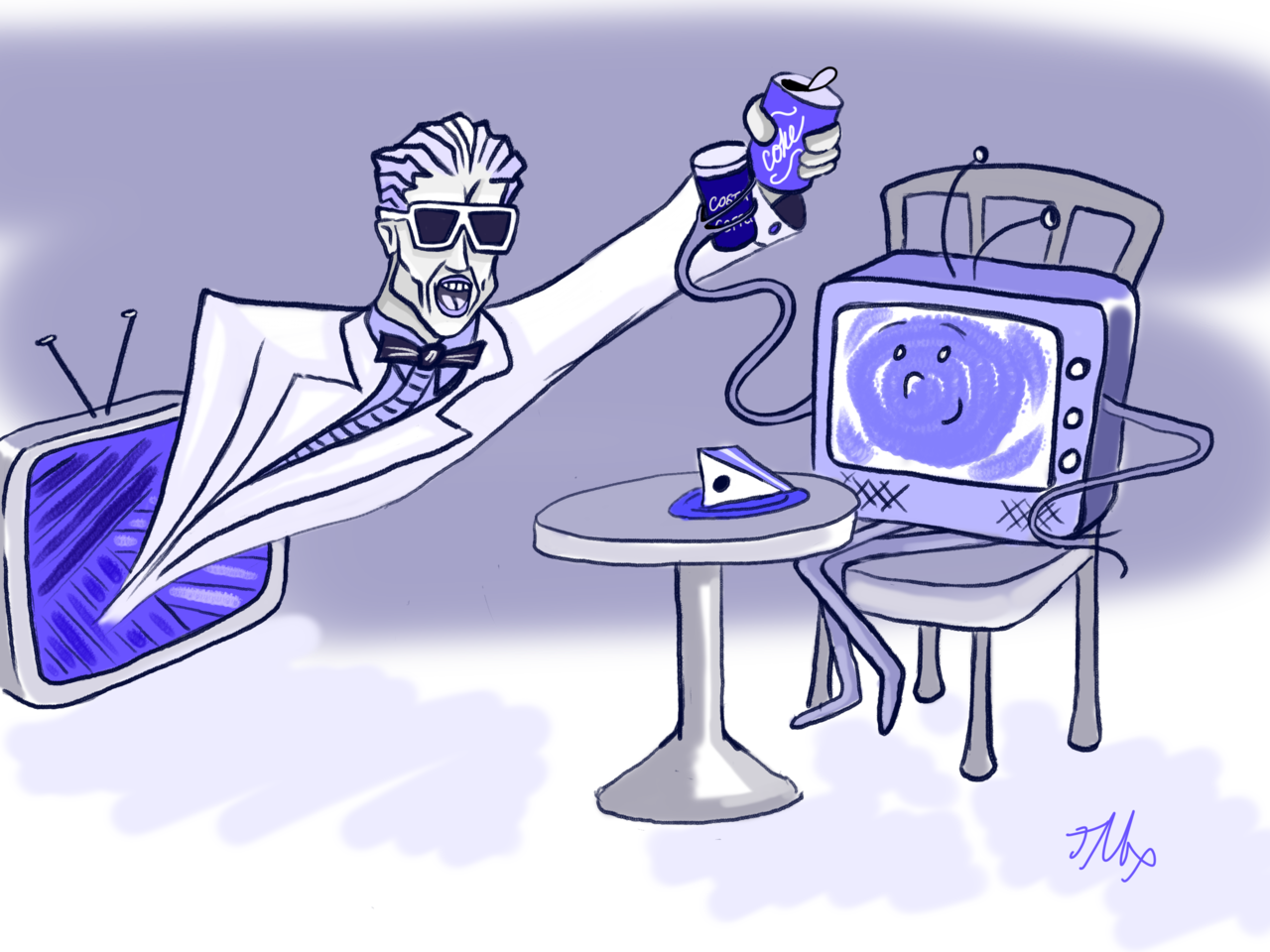

On a chilly Sunday night in November 1987, Chicago TV viewers were just trying to watch the news or catch up on Doctor Who. They didn't expect a nightmare. Out of nowhere, the screen flickered into static. A man wearing a rubber mask of the digital character Max Headroom appeared, bobbing against a spinning sheet of corrugated metal. He laughed. He moaned. He held up a Pepsi can. Then, he got spanked with a flyswatter.

It was weird. It was jarring. And nearly four decades later, the Max Headroom broadcast intrusion remains the most famous unsolved mystery in the history of American television.

People talk about "hacking" today like it's all lines of code and firewalls. Back then, hacking was physical. It was about radio waves, massive antennas, and knowing exactly where to point a dish. This wasn't some kid in a basement with a laptop; it was a high-stakes hijacking of the airwaves that baffled the FCC and the FBI. Even now, the internet is obsessed with finding the culprits. But honestly? We might never know who they were.

What Actually Happened During the Max Headroom Broadcast Intrusion?

The night of November 22, 1987, saw two separate attacks. The first was a "dry run" during WGN-TV’s 9:00 PM news. Dan Roan, a local sports anchor, was mid-sentence when the signal just... died. The screen went black, then the masked figure showed up for about 30 seconds. There was no audio, just a buzzing sound. WGN engineers reacted fast. They switched their microwave link to a different frequency, and Roan was back on screen, looking genuinely confused. "Well, if you're wondering what happened, so am I," he told the audience.

But the hackers weren't done.

About two hours later, they struck again. This time, they hit WTTW, the local PBS station, during an episode of the Doctor Who serial "Horror of Fang Rock." Because WTTW's transmitter was located atop the Sears Tower (now Willis Tower) and didn't have engineers on duty at that specific master control site at night, the intruders had more time. For roughly 90 seconds, the masked man rambled. He mocked WGN pundit Chuck Swirsky. He hummed the theme to Clutch Cargo. He threw a Pepsi can.

Then came the weirdest part: the man leaned over, exposed his backside, and a woman in a French maid outfit started hitting him with a flyswatter. "They’re coming to get me!" he yelled. The signal finally cut out because WTTW technicians at another location couldn't figure out how to stop the override without shutting down the entire broadcast.

The Technical Mystery of the Signal Jacking

How did they do it? Basically, it’s a matter of "overpowering" the legitimate signal. In the 80s, TV stations sent their signal from the studio to the transmitter via a Microwave Studio-to-Transmitter Link (STL).

If you had a powerful enough microwave transmitter and a clear line of sight to the station's receiving antenna, you could beam your own signal at it. If your signal was stronger than the one coming from the studio, the transmitter would pick up yours and broadcast it to the whole city.

👉 See also: Finding the Right Destroyed Palace No Background Images for Your Design Project

It sounds simple, but it required some serious gear. You’d need a high-gain dish and a lot of power. We’re talking thousands of dollars of equipment in 1987 money. This wasn't a prank pulled off with a hijacked walkie-talkie. The attackers likely set up in a van or on a rooftop somewhere in the Chicago area, pointed their gear at the Sears Tower and the John Hancock Center, and let it rip.

Why the FBI Couldn't Crack the Case

The FCC went into full investigation mode. They knew this was a federal crime. Breaking the Communications Act of 1934 carries heavy fines and jail time. They tracked down the "Max Headroom" mask—it was a popular item sold at many costume shops—but that was a dead end.

The audio was the biggest clue, yet it was so distorted it was almost useless. Investigators looked into former station employees, disgruntled tech nerds, and local video enthusiasts. They even checked out "Captain Midnight," a man named John R. MacDougall who had hijacked HBO a year earlier to protest high scrambling fees. But MacDougall had already been caught and was under a bright spotlight. It wasn't him.

The "Eric V." Theory

If you spend any time on Reddit or old-school tech forums, you’ve heard of the "Eric V." theory. In 2010, a programmer named Chris Knittel wrote a long post claiming he knew who did it. He pointed to a man he knew in the 1980s Chicago hacker scene—a guy he called "Eric V." who was on the autism spectrum, had access to heavy-duty video gear, and lived in a house that matched some of the background details of the video.

It’s a compelling story. Knittel described Eric as a brilliant but eccentric guy who felt alienated from the world. But here's the thing: it’s all circumstantial. There’s no physical evidence. No one has ever confessed. No one found the flyswatter or the corrugated metal backdrop. The theory remains just that—a theory.

The Cultural Legacy of Max Headroom

Why do we care so much? Maybe it’s because the Max Headroom broadcast intrusion feels like a glitch in the Matrix. It’s a moment where the "authorized" reality of television was broken by something chaotic and weird. Max Headroom himself was supposed to be a "computer-generated" character (even though he was actually an actor in makeup), representing a slick, corporate future. To see a low-budget, filthy version of that character mocking the system was pure cyberpunk.

It was a pre-internet meme. Long before "trolling" was a word, these guys were doing it to an entire metropolitan area.

Misconceptions About the Hack

- It was a digital hack: Nope. This was analog radio frequency hijacking. No computers were involved in the actual transmission.

- The hackers were caught: Some people confuse this with the Captain Midnight or "Zombie" incidents. To this day, the Max Headroom intruders have never been officially identified.

- The audio was a secret message: People have spent years slowed-down and filtering the audio. Most experts agree it’s just nonsense—puns about "The Greatest World's Newspaper" (WGN) and random pop culture references.

The Reality of Airwave Security Today

Could this happen again? Honestly, it’s much harder now. Most television signals are digital and encrypted. The transition from analog to digital in the late 2000s added layers of complexity that make a simple "power override" much less effective. Modern STLs often use fiber optics instead of microwave links, meaning there’s no signal in the air to hijack until it leaves the main transmitter.

But hackers move with the times. Instead of hijacking a signal with a dish, they hijack social media accounts or streaming platforms. We’ve seen "hacks" of emergency alert systems in small towns where people play "zombie apocalypse" warnings. It’s the same spirit of mischief, just a different medium.

📖 Related: Apple Store Pleasanton CA 94588: What to Know Before You Head to Stoneridge Mall

Lessons from the Mystery

The Max Headroom incident taught the industry about the vulnerability of "clear" signals. It showed that even the most prestigious news organizations could be silenced by someone with enough technical know-how and a grudge.

If you're fascinated by this, you can actually dig deeper into the technical side. Many of the FCC's original documents are available via FOIA requests. You can see the diagrams of how the signals were routed. It's a masterclass in 80s telecommunications.

What You Can Do Next

To really understand the scale of this, you should watch the original footage. It's widely available on archival sites. Pay attention to the background—the spinning metal. Some researchers believe that piece of metal is the key to finding the location where the video was filmed.

- Analyze the "Sears Tower" Line of Sight: If you're in Chicago, look at the geography between the old WTTW offices and the Sears Tower. You can start to map out where a pirate transmitter would have to be stationed to hit that target.

- Research the "Great Lakes" Hacker Culture: The 1980s Chicago phreaking and hacking scene was vibrant. Reading old "Zines" like 2600 can give you a vibe of what these people were thinking.

- Check the FCC Public Files: If you're a real tech geek, the technical specs of the STL links used in 1987 are still on record. Understanding the wattage needed to override a 7-kilowatt signal is a fun math problem for an afternoon.

The case is cold, but it’s not dead. Every few years, someone comes forward with a new "I knew the guy" story. Until then, the man in the mask remains a ghost in the machine, a reminder that the systems we trust are often more fragile than they look. It’s a bit of history that remains beautifully, frustratingly unexplained.