Imagine you’re floating in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. You have no engine. No radio. Your boat, a 31-foot yacht named Auralyn, is currently at the bottom of the sea because a sperm whale decided to ram it. This isn't a movie plot; it's exactly what happened to a British couple in 1973. If you look at a Maurice and Maralyn Bailey map of their drift, it looks like a chaotic, squiggly line of desperation across thousands of miles of blue nothingness.

Most people think survival is about gear. Honestly? For the Baileys, it was about a notebook, some crude drawings, and a terrifying amount of patience. They spent 117 days—nearly four months—in a rubber circular life raft and a tiny dinghy.

They weren't sailors by trade, not really. Maurice was a printer; Maralyn was a tax officer. They wanted to start a new life in New Zealand. Instead, they ended up in a fight for their lives that changed how we understand human endurance.

Why the Maurice and Maralyn Bailey Map Matters Today

When you study the Maurice and Maralyn Bailey map, you're looking at a journey that started about 250 miles north of the Galapagos Islands. On March 4, 1973, their world literally broke apart. A whale struck their hull, and within minutes, they were tossing whatever they could grab into a four-man Avon life raft.

They had some tins of food, a few gallons of water, a butane stove, and—crucially—a map and a compass. But a map doesn't do much when you have no oars and no sail. You're just a speck. You're a passenger on the Humboldt Current.

The current is the real architect of the Maurice and Maralyn Bailey map. It pushed them west, away from the coast of South America, into the vast, empty "deserts" of the Pacific. If you track their coordinates from their diaries, you see they weren't just moving in a straight line. They were looping. They were circling. They were watching ships pass them by—seven ships in total—none of which saw the tiny yellow dot on the horizon.

📖 Related: Finding Your Way: What the Tenderloin San Francisco Map Actually Tells You

The Brutal Reality of the Drift

Survival wasn't just about hunger. It was the skin sores. It was the salt spray.

They survived on raw turtles, seabirds, and sharks. Yeah, they caught sharks by hand. Think about the guts that takes. They would lean over the side of a rubber raft, grab a shark by its tail, and haul it aboard. Maralyn would pin the head while Maurice dealt the killing blow. They ate the hearts, the livers, and even drank the turtle blood when the rain didn't fall.

People often ask about the "map" they kept. It wasn't just a navigational tool; it was their sanity. Maurice kept a diary and made sketches. These drawings, later published in their book 117 Days Adrift, are perhaps the most famous part of the Maurice and Maralyn Bailey map legacy. They documented every bird they saw, every fish they caught, and the slow, agonizing passage of time.

Mapping the Mind

Looking at the coordinates they recorded, you see the psychological toll.

- Day 20: Still hopeful.

- Day 50: The raft is losing air. They have to pump it up every few hours.

- Day 90: They are essentially skeletons. Maurice had lost about 40 pounds; Maralyn nearly the same.

The Maurice and Maralyn Bailey map shows they drifted approximately 1,500 miles. Think about that distance. That's like floating from New York to Cuba, but with no control over your direction and a constant fear that a shark’s dorsal fin will puncture your only floor.

👉 See also: Finding Your Way: What the Map of Ventura California Actually Tells You

The Rescue and the Legacy

They were finally picked up by a South Korean fishing boat, the Weolmi 306, on June 30, 1973. The sailors didn't even see them at first. It was only because the ship slowed down to pull in their lines that they spotted the raft.

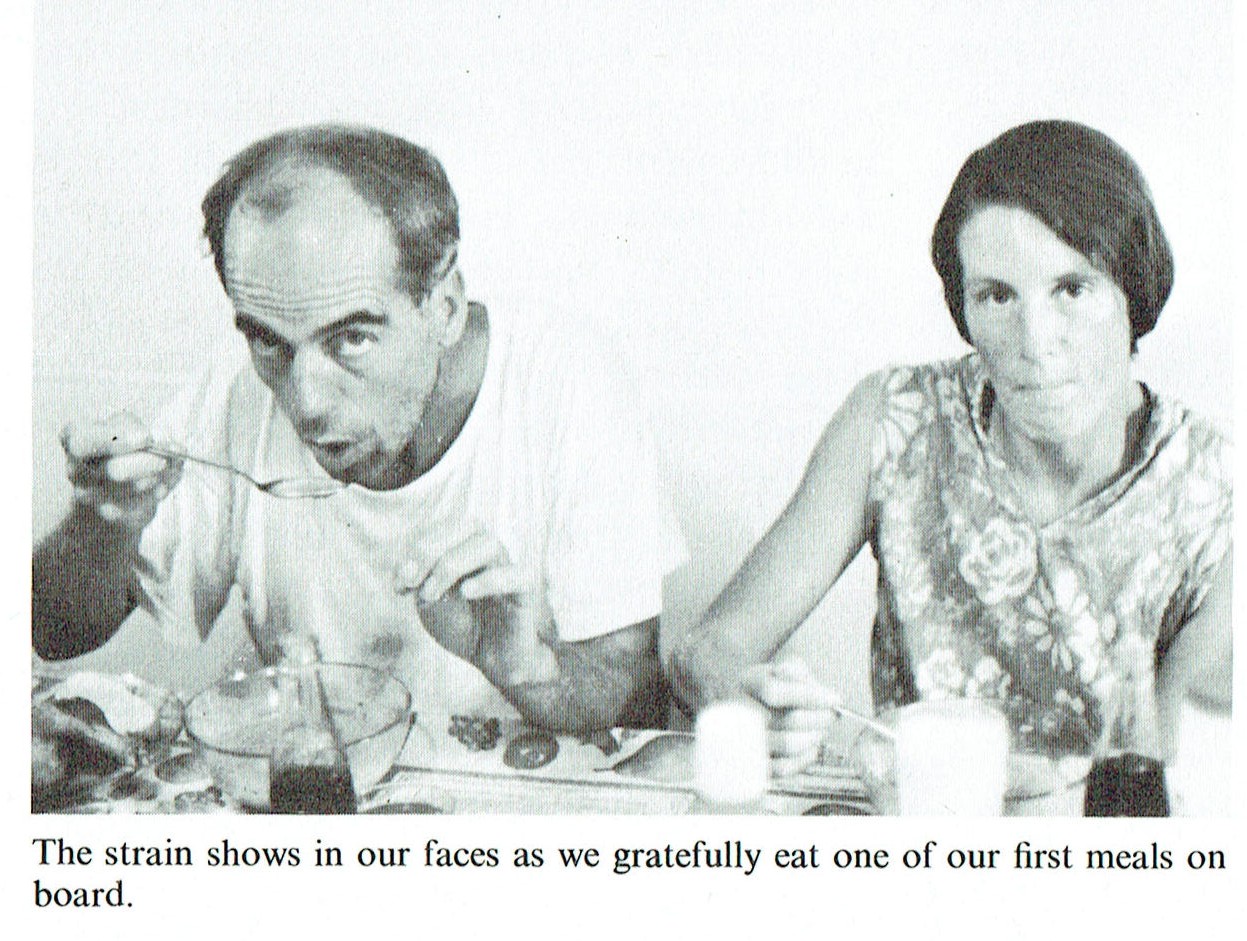

When they were pulled on board, they could barely stand. Their legs had essentially withered from lack of use. Their stomachs couldn't handle solid food. But they had their notes. They had their map.

What’s wild is that they didn't quit the sea. After recovering, they built another boat! Most of us wouldn't even go near a bathtub after that, but they were back on the water within a few years. They eventually wrote their book, which remains a cornerstone of survival literature. It’s a case study in "active survival"—the idea that you don't just wait to be saved; you work every second to stay alive.

Technical Limitations of the 1970s

We have to remember this was before GPS. No EPIRBs. No satellite phones.

The Maurice and Maralyn Bailey map was created using a plastic sextant and a lot of guesswork. Today, if your boat sinks, your watch probably sends a distress signal to a satellite. In 1973, you were just gone. The fact that they maintained a sense of where they were on the globe is a testament to Maurice’s discipline.

✨ Don't miss: Finding Your Way: The United States Map Atlanta Georgia Connection and Why It Matters

Lessons From the 1,500-Mile Drift

If you’re a sailor, or even just someone fascinated by human limits, there are tangible takeaways from the Baileys' ordeal. It wasn't luck. Well, maybe a little luck. But it was mostly routine.

- Routine kills panic. They kept "ship's time." They had chores. They didn't just sit and stare at the waves.

- Resourcefulness over gear. They used safety pins to make fish hooks. They used a bucket to catch rain.

- The power of documentation. Keeping that diary and marking their Maurice and Maralyn Bailey map gave them a future-facing goal. It turned their suffering into a "story" they were currently writing.

What to Do if You Want to Trace Their Journey

Tracing the Maurice and Maralyn Bailey map today is a fascinating exercise for armchair historians and maritime geeks. You can actually find their original raft on display at the National Maritime Museum Cornwall in the UK. Seeing it in person is a shock. It’s tiny. It’s a miracle they both fit, let alone survived for a third of a year in it.

If you’re looking to dive deeper into the specifics of their route, you should track down a first-edition copy of 117 Days Adrift. The illustrations in there aren't just art; they are the literal map of two people refusing to die.

You can also cross-reference their drift patterns with modern oceanographic data of the Humboldt and Equatorial currents. It’s a sobering look at how the ocean moves everything toward the west, into the deep "desert" of the Pacific. For those interested in survival gear, comparing the 1970s Avon raft to modern ISO-certified life rafts shows just how far safety tech has come—and how much the Baileys lacked.

Actionable Steps for Maritime Enthusiasts

- Visit the Artifacts: Go to the National Maritime Museum Cornwall to see the actual raft. It puts the scale of the Maurice and Maralyn Bailey map into a terrifying perspective.

- Study Current Patterns: Use tools like EarthNullSchool to look at the Humboldt Current. It helps you visualize why the Baileys drifted where they did.

- Read the Source Material: Skip the summaries and read 117 Days Adrift (also published as Staying Alive!). It’s the raw, unvarnished look at their daily logs.

- Check Survival Equipment: If you're a boat owner, use this story as a prompt to check your own "ditch bag." Do you have the basics for long-term survival, or just 24 hours?

The story of the Baileys isn't just about a shipwreck. It's about what happens when "normal" people are pushed to the absolute edge of the map and decide to keep drawing the line anyway.