You wouldn't expect to find life-saving medical breakthroughs between a bearded lady and a roller coaster. But for decades, that’s exactly where it happened. If you were a parent with a "weakling" child in 1903, the hospital probably told you to give up. They didn't have the tech. They didn't have the hope. Then there was Dr. Martin Couney. Or "Doctor" Couney, depending on who you ask, since he likely faked his medical credentials.

He took these tiny, struggling infants and put them in glass boxes. He charged people a quarter to stare at them. It sounds like a horror movie, right? Exploitative. Gross. Unethical.

But here’s the thing: he saved thousands of lives.

The Martin Couney premature babies were the first generation of humans to survive the "un-survivable." While the medical establishment dismissed premature infants as "genetically inferior" or simply "not meant to be," Couney was busy sanitizing his exhibits and hiring wet nurses. He turned the spectacle of the Coney Island boardwalk into a sophisticated, high-tech nursery that predated modern Neonatal Intensive Care Units (NICUs) by nearly half a century.

The Man Who Sold Survival for Twenty-Five Cents

Martin Couney wasn't a tall man, but he had a massive presence. Born Michael Cohen in Poland, he eventually moved to Berlin and then Paris, where he claimed to have studied under Pierre-Constant Budin. Budin was the guy who basically invented modern perinatal medicine. Whether Couney actually sat in those classrooms is a point of huge debate among historians like Dawn Raffel, who wrote The Strange Case of Dr. Couney.

He arrived in the U.S. and realized the hospitals here were essentially death traps for preemies. They didn't have incubators. They thought keeping a baby warm was enough. Couney knew better. He knew it was about the air. He knew it was about the germs.

He didn't have a hospital wing. He had a show.

At Dreamland and later Luna Park in Coney Island, he set up "All the World Loves a Baby." People paid 25 cents. That quarter paid for the nurses. It paid for the expensive, state-of-the-art Lion incubators imported from Europe. It paid for the ventilation systems that pulled fresh air from the outside. The parents? They paid nothing. Couney never charged a mother or father a single cent to save their child.

📖 Related: Whooping Cough Symptoms: Why It’s Way More Than Just a Bad Cold

The Tech Inside the Glass Boxes

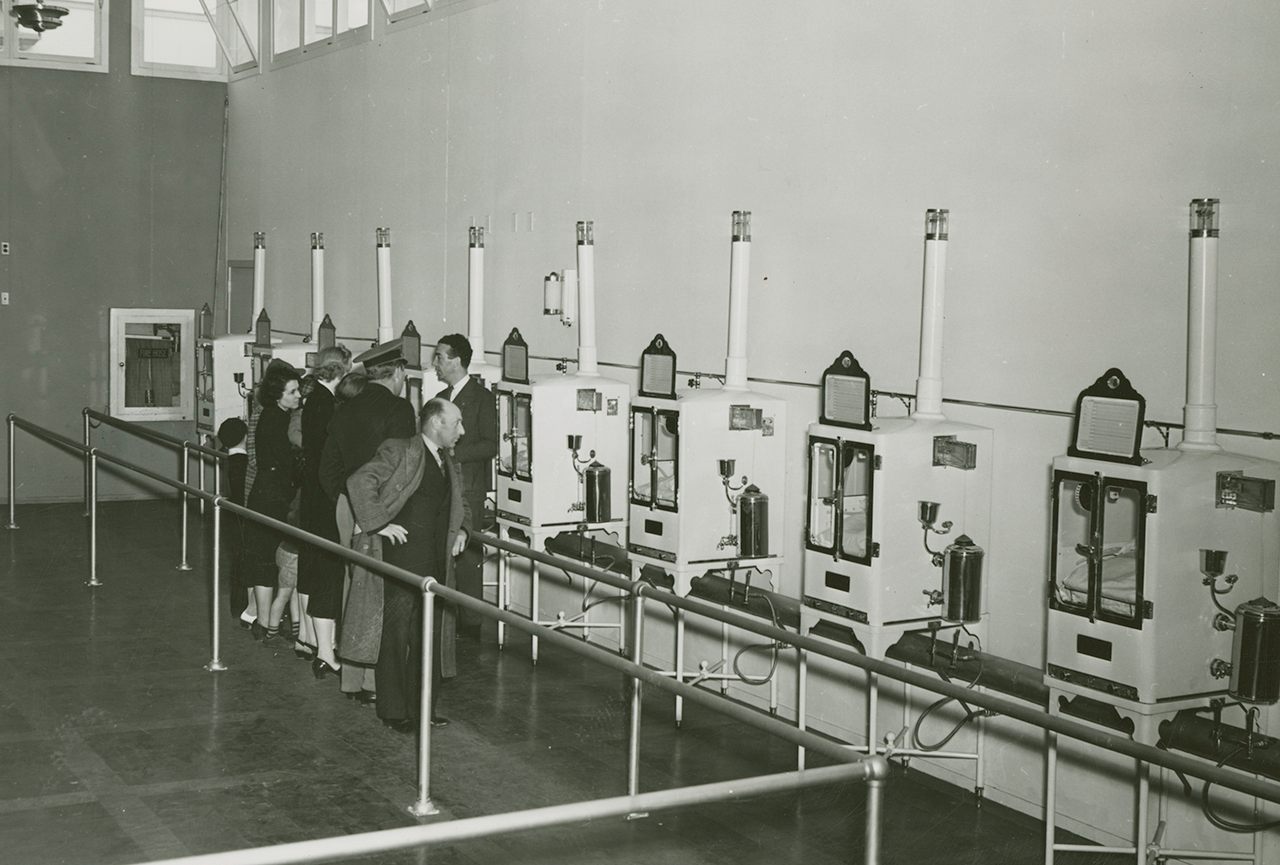

Those incubators weren't just boxes. They were marvels of engineering for the time. Each one was about five feet tall, made of steel and glass. A water boiler underneath kept the temperature steady. A pipe through the wall brought in outside air, filtered through medicated absorbent cotton.

Then there was the "exhaust" pipe. It let the hot, stale air out.

Couney was a stickler for hygiene. This was a time when doctors often didn't wash their hands between patients. In Couney’s exhibit, the nurses wore starched white uniforms. The floors were scrubbed constantly. If a nurse was caught smoking or drinking, she was fired on the spot. He insisted on breastfeeding, and if a mother couldn't provide milk, he hired wet nurses who were kept on a strict diet. No spicy food. No alcohol.

It was a controlled environment. A laboratory.

Inside, the Martin Couney premature babies thrived. They were tiny. Some weighed less than two pounds. They looked like "dolls," according to contemporary newspaper reports. People would crowd around the glass, watching a tiny hand twitch or a chest rise and fall. It was the most popular attraction on the boardwalk.

Why the Medical World Hated Him

The American Medical Association (AMA) wasn't exactly a fan. They saw Couney as a charlatan. A carny. They accused him of "advertising," which was a massive no-no for doctors back then.

They weren't wrong about the spectacle. Couney was a showman. He’d dress the babies in clothes that were way too big for them to emphasize how small they were. He’d show off a baby wearing a wedding ring as a bracelet. He knew how to get a crowd.

👉 See also: Why Do Women Fake Orgasms? The Uncomfortable Truth Most People Ignore

But he had results.

While hospitals were seeing mortality rates of 80% or 90% for premature infants, Couney was boasting a survival rate of around 85%. Think about that. He was doing better in a carnival than the best doctors in Manhattan were doing in sterile wards.

One of his most famous "graduates" was his own daughter, Hildegard. She was born six weeks early and weighed three pounds. He put her straight into an incubator in his exhibit. She lived to be an adult, working alongside him as a nurse.

The Atlantic City Connection and the End of an Era

It wasn't just Coney Island. Couney took his show on the road. He had a permanent installation on the Steel Pier in Atlantic City. He went to the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair.

That Chicago fair was a turning point. A local pediatrician named Dr. Julius Hess—who is often called the father of American neonatology—visited the exhibit. Unlike his peers, Hess didn't look down his nose at Couney. He saw the data. He saw the healthy babies.

Hess and Couney actually became friends. They collaborated on an incubator design. Slowly, the medical world started to realize that the "carny" was right.

By the late 1930s, hospitals finally started opening their own premature infant stations. Cornell's New York Hospital opened one in 1932. As the technology moved into the hospitals, the need for the sideshow vanished.

✨ Don't miss: That Weird Feeling in Knee No Pain: What Your Body Is Actually Trying to Tell You

Couney died in 1950, almost broke. He had spent most of his earnings on the care of the children. He lived long enough to see his "spectacle" become standard medical practice.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Exhibits

There’s this idea that Couney was just a greedy guy exploiting kids. That's a bit of a reach. If you look at the testimonials from parents, they didn't feel exploited. They felt grateful.

Take the story of Lucille Horn. She was born in 1920. The hospital told her parents she wouldn't make it. Her father hailed a taxi, put her in a box, and drove her straight to Couney’s exhibit. She lived to be 96 years old. She used to go back to Coney Island and stand by the incubators to talk to people.

The "freak show" label misses the point. The babies weren't the freaks; the technology was the attraction. People weren't there to mock. They were there to witness a miracle.

The Legacy of the Boardwalk Babies

We talk a lot about "disruptive innovation" in tech today. Couney was the original disruptor. He didn't wait for the medical boards to approve his methods. He didn't wait for a grant. He used the only funding model available to him: entertainment.

Today’s NICUs are quieter. They don't have barkers outside. But the DNA of every modern incubator—the filtered air, the temperature control, the emphasis on specialized nursing—can be traced back to a man who shouted for people to "See the babies!" over the sound of a carousel.

It’s a weird, slightly uncomfortable chapter in medical history. It challenges our ideas of what "ethical" care looks like. If a carnival is the only place your child can live, do you care about the ethics of the ticket price? Probably not.

Lessons and Actionable Insights from the Couney Era

Understanding the history of the Martin Couney premature babies provides more than just a history lesson; it offers a lens through which we can view modern medical advocacy and patient care.

- Question "Un-survivability": Couney proved that "standard of care" is often just a lack of imagination or resources. If you are facing a medical diagnosis that seems hopeless, look for specialists or centers that are pushing boundaries, even if they are outside the traditional mainstream.

- The Power of Specialized Nursing: One of Couney’s secrets was the 1:1 or 1:2 nurse-to-baby ratio. In modern healthcare, the quality of nursing care is often the strongest predictor of recovery. When choosing a facility, ask about their staffing ratios.

- Sanitization is King: Couney’s survival rates were high because he was obsessed with cleanliness before it was cool. In any home-care or hospital setting, maintaining a rigorous hygiene protocol is the simplest way to prevent secondary complications.

- Advocate for Transparency: Couney’s "exhibits" were actually more transparent than most hospital wards of the time. While we don't need crowds, having family members present and involved in the "NICU journey" is now recognized as vital for infant development (often called Family-Centered Care).

- Support Medical History Research: To understand where we are going, we have to know where we started. Organizations like the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) maintain archives that show the evolution of these life-saving technologies.

The story of Martin Couney reminds us that sometimes, the most serious work in the world happens in the most unexpected places. He took the "weaklings" and turned them into survivors, one quarter at a time.