Ever looked at a map of the United States and noticed those irregular, shaded patches scattered mostly across the West? You're looking at a map US indian reservations setup that is far more complex than just "land set aside." Honestly, most people think these areas are just historical relics or static boundaries. They aren't. They are living, breathing sovereign nations with legal tangles that would make a corporate lawyer's head spin.

It's messy.

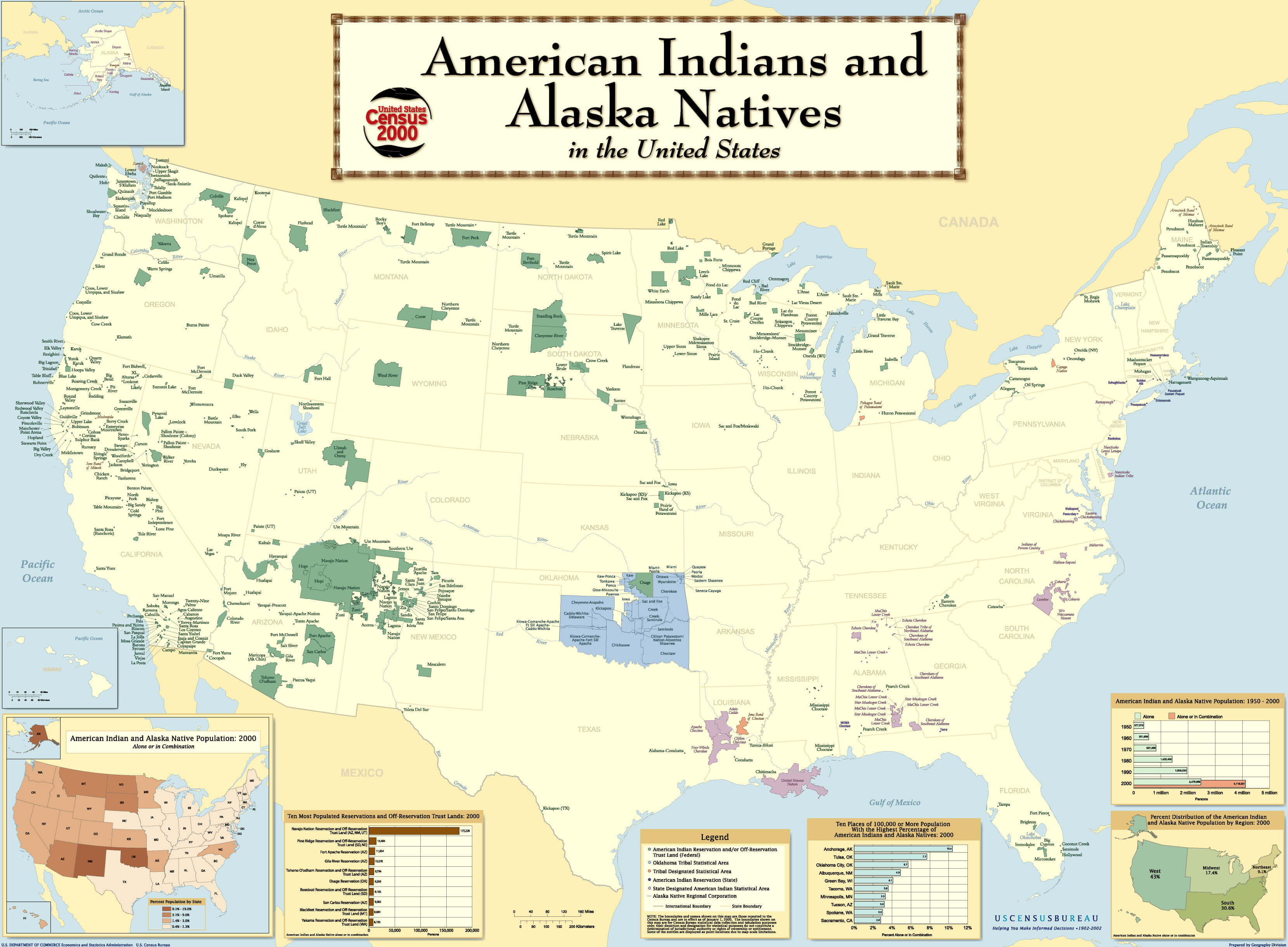

There are roughly 326 federally recognized Indian reservations in the United States. That sounds like a lot until you realize there are 574 federally recognized tribes. Do the math. Not every tribe has a land base. Some share land. Others have "off-reservation trust land" that doesn't always show up on your standard Google Maps view. When you pull up a map US indian reservations, you're seeing a snapshot of a centuries-long struggle over jurisdiction, water rights, and basic survival.

Why the Map US Indian Reservations Look So Strange

If you look at a map of the Navajo Nation—the largest reservation in the country—it’s roughly the size of West Virginia. It sprawls across Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. But then look at Oklahoma. For a long time, maps didn't even show "reservations" there because of the way the state was formed through the dissolution of tribal governments during the allotment era.

That changed recently.

In 2020, the Supreme Court dropped a bombshell with McGirt v. Oklahoma. Suddenly, a huge chunk of eastern Oklahoma was legally recognized as Indian Country for the purposes of the Major Crimes Act. If you were looking at a map US indian reservations before and after that ruling, the visual shift is staggering. It reminds us that these borders aren't just lines on paper; they are dictated by Supreme Court justices and treaties from the 1800s that are still very much active.

The Checkerboard Nightmare

Here is something truly wild. Inside the boundaries of many reservations, the tribe might not actually own all the land. This is called "checkerboarding." Back in the late 19th century, the Dawes Act broke up communal tribal lands into small individual plots. The "surplus" was sold to non-Native settlers.

💡 You might also like: Robert Hanssen: What Most People Get Wrong About the FBI's Most Damaging Spy

The result? A nightmare.

You can walk ten feet and move from tribal trust land to fee-simple land owned by a private corporation, then back to tribal land. This makes law enforcement a total headache. If a crime happens on a reservation, the question of who has jurisdiction—the FBI, the tribal police, or the county sheriff—depends entirely on exactly where the person was standing and whether the victim was Native American.

Beyond the Big Names: Small Lands, Big Impact

Everyone knows the Navajo or the Pine Ridge Reservation. But look closer at a map US indian reservations in the Pacific Northwest or California. You’ll see tiny specks. Some are just a few acres.

- The Augustine Reservation in California once had only one adult resident.

- In contrast, the Tohono O'odham Nation in Arizona shares a 62-mile border with Mexico.

The geographical diversity is insane. You have reservations that are literal deserts and others that are lush coastal rainforests. Some tribes, like the Quinault in Washington, are literally moving their entire villages because of rising sea levels. Their map is changing in real-time because the Pacific Ocean is swallowing their land.

Sovereignty is the Real Story

A reservation isn't a "county." It’s a sovereign territory. When you cross that boundary, you are entering a space where the tribe has its own laws, its own courts, and its own taxes. This is why you see smoke shops and casinos, sure, but it's also why tribal nations are leading the way in environmental conservation. They often have stricter environmental codes than the states surrounding them.

Think about the Nez Perce in Idaho. They have been instrumental in restoring gray wolf populations. Their "map" isn't just the reservation boundary; it's their traditional hunting and fishing grounds guaranteed by the Treaty of 1855. These "usual and accustomed places" often extend far beyond the shaded areas on a standard map US indian reservations.

📖 Related: Why the Recent Snowfall Western New York State Emergency Was Different

What People Get Wrong About "Giving Back" Land

There is a lot of talk about the "Land Back" movement. People sometimes assume this means kicking everyone off their ranches in Montana. That's not really the vibe. Mostly, it's about the federal government returning management of "public" lands—like National Parks—to the tribes who were forcibly removed from them.

Take the Blackfeet Nation in Montana. They share a border with Glacier National Park. To a tourist, it’s a park. To the Blackfeet, it’s the "Backbone of the World." They never actually gave up their rights to that land; it was essentially swindled from them in a 1895 agreement that they claim was misunderstood. When you look at a map US indian reservations in that region, you have to look at the "ceded territories" to understand the full picture.

The Role of the BIA

The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) holds the title to most reservation land "in trust." This means tribes can't just sell their land to a developer. It's a layer of protection, but it's also a layer of bureaucracy. If a tribe wants to build a house or a school, they often have to get federal approval. It’s a weird, paternalistic relationship that dates back to the Marshall Trilogy of Supreme Court cases in the 1820s and 30s which labeled tribes as "domestic dependent nations."

Visualizing the Data: Where the People Are

Data from the US Census Bureau is actually a great way to see how the map US indian reservations population is shifting. Not everyone who lives on a reservation is Native American. In some places, like the Flathead Reservation in Montana, non-Natives actually outnumber tribal members.

This creates a unique cultural melting pot, but it also creates friction.

Who gets to vote for the local school board? Who pays for the roads? These are the questions that arise when you have a map where jurisdictions overlap like a Venn diagram designed by a madman.

👉 See also: Nate Silver Trump Approval Rating: Why the 2026 Numbers Look So Different

Urban vs. Reservation Life

Believe it or not, roughly 70% of Native Americans don't live on reservations. They live in cities like Phoenix, Los Angeles, and Minneapolis. This happened largely because of the Indian Relocation Act of 1956, which encouraged people to leave reservations for urban jobs.

So, while the map US indian reservations is vital for legal and political reasons, it doesn't represent the full scope of Native life in America. There are "urban Indian centers" that act as cultural hubs, even if they aren't shaded orange or green on a map.

The Future of Tribal Mapping

Technology is changing how we see these lands. Tribal GIS (Geographic Information Systems) departments are now using drones and satellite imagery to map their own resources, from water tables to ancient cultural sites. They aren't relying on the federal government’s maps anymore.

They are making their own.

This is a huge deal for things like the Colorado River water rights. If you look at a map US indian reservations in the Southwest, you’re looking at a map of who has the legal right to the water that keeps Los Angeles and Phoenix alive. If the tribes decided to fully exercise their senior water rights, the map of the American West would look very different, very quickly.

Actionable Insights for Navigating Tribal Lands

If you are traveling through or researching these areas, don't just treat the map as a suggestion.

- Check Local Laws: Tribal law is the law of the land. Speed limits, fishing licenses, and even alcohol laws (some reservations are "dry") are determined by the tribe.

- Respect Private Property: Just because it's a reservation doesn't mean it's "public land." People live there. It's their home. Don't wander into backyards or sensitive cultural sites.

- Use Official Tribal Resources: If you want to visit, check the tribe's official website. Many have incredible museums, like the Tamástslikt Cultural Institute in Oregon, which give a perspective you won’t find in a history textbook.

- Support Tribal Economies: If you're using the map US indian reservations to plan a road trip, buy your gas, food, and art from tribal-owned businesses. It makes a direct impact on the community.

The map of Indian Country is a map of survival. It shows where people were pushed, but it also shows where they dug in and stayed. It’s a testament to resilience. Next time you see those shaded patches, remember that they represent some of the oldest continuous governments on the planet. They aren't just remnants; they are the future of how we manage land, water, and sovereignty in the 21st century.

If you’re digging into this for research or travel, your next move should be to look up the specific tribal government's website for the area you're interested in. Maps tell you where the borders are, but the people who live there will tell you what the land actually means. Access the Integrated Resource Management Plans (IRMP) if you really want to see how a tribe plans to use its map for the next fifty years. It’s fascinating stuff.