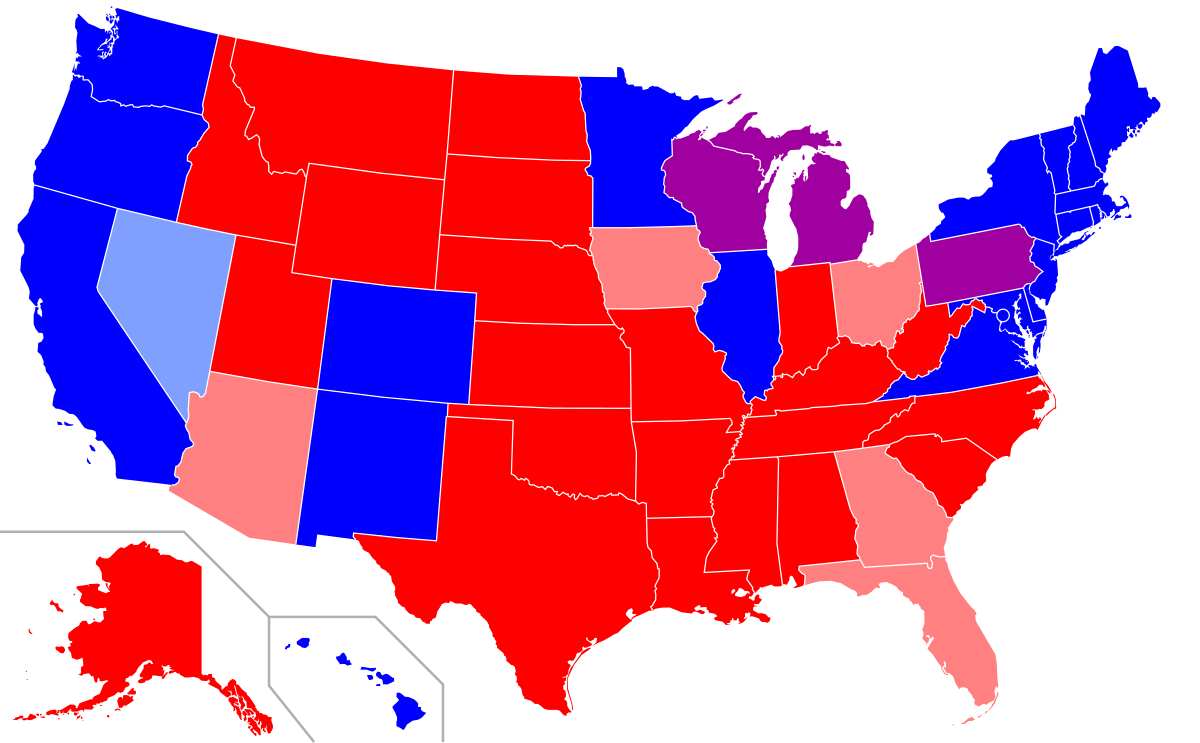

You’ve seen it a thousand times. Every four years, television screens across the country bleed into a binary mosaic of neon crimson and deep azure. It looks like a country divided into two neat, monolithic blocks. But that's a lie. Well, maybe not a lie, but it’s definitely a massive oversimplification that hides how Americans actually live and vote.

The map of US blue and red states has become the visual shorthand for our national identity. We use it to decide where to move, which businesses to support, and who we can talk to about politics at Thanksgiving. Yet, if you look closer at the actual data from the 2020 and 2024 cycles, the "sea of red" and "islands of blue" narrative starts to crumble.

Geography isn't destiny.

Why the Map of US Blue and Red States Looks So Misleading

Land doesn't vote. People do.

That’s the first thing any political geographer like Kenneth C. Martis would tell you. When you look at a standard geographic map of the US, it looks like the Republican party has a massive, overwhelming majority because red counties cover about 80% of the physical landmass. But humans aren't spread out evenly. We huddle. We cluster in cities.

Take a state like Illinois. If you look at a map of its counties, it’s almost entirely red. However, because Cook County (Chicago) is so densely populated, the state remains a lock for the Democrats. This creates a "cartographic illusion." The map makes it look like the country is a red desert with a few blue oases, when in reality, the population is split almost down the middle.

There’s also the issue of the "Winner-Take-All" system used by 48 states. If a candidate wins a state by 0.1% of the vote—like the razor-thin margins we saw in Georgia or Arizona in 2020—the entire state turns one color on the map. This erases the millions of people who voted the other way. There are more Republican voters in California than in several "red" states combined. There are more Democrats in Texas than in many "blue" New England states. You wouldn't know that by looking at the standard map.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Air France Crash Toronto Miracle Still Changes How We Fly

The Rise of the Purple Suburb

Suburbs are where the real action is. For decades, the divide was simple: cities were blue, rural areas were red. The suburbs were the swing zone, often leaning Republican for "law and order" or tax reasons. That's changing.

We’re seeing a massive shift in the "collar counties" around cities like Philadelphia, Atlanta, and Phoenix. These areas are turning a distinct shade of lavender. High-education voters in the suburbs have been drifting toward the Democratic column, while working-class voters in the same regions are often sticking with or moving toward the GOP. It’s a messy, chaotic tug-of-war that a two-color map just can’t capture.

The History Behind the Colors (It’s Newer Than You Think)

Believe it or not, the colors weren't always fixed.

Before the 2000 election between George W. Bush and Al Gore, there was no standard. Some networks used blue for Republicans (B for Blue, B for Bush) and red for Democrats. In fact, for a long time, red was associated with left-leaning parties globally—think of the "Red Menace" or the British Labour Party.

The 2000 recount changed everything. Because the Florida dispute dragged on for weeks, the maps stayed on our screens every single night. The media collectively settled on Red for GOP and Blue for Dems. It stuck. Now, it’s part of our vocabulary. We talk about "Blue Walls" and "Red Bastions" as if these colors were etched into the Constitution. They weren't. They’re a television production choice that became a cultural reality.

The "Blue Wall" and Its Cracks

Political junkies love talking about the Blue Wall. This refers to a group of 18 states (plus D.C.) that voted Democratic in every election from 1992 to 2012. It included the "Rust Belt" trio: Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin.

🔗 Read more: Robert Hanssen: What Most People Get Wrong About the FBI's Most Damaging Spy

Then came 2016.

Donald Trump flipped those three states, shattering the wall. In 2020, Joe Biden won them back. In 2024, the margins in these states remained within a few percentage points. This tells us that the map of US blue and red states is far more fluid than we like to admit. A state isn't "blue" because of its soil; it’s blue because of a specific coalition of voters that can dissolve at any moment.

Cartograms: A Better Way to See the Country

If you want to see what America actually looks like, stop looking at geographic maps. Look at cartograms.

A cartogram distorts the size of states based on their population or Electoral College votes. In these maps, Rhode Island looks huge and Montana looks like a tiny sliver. It’s ugly. It’s jarring. But it’s honest. It shows that the "blue" areas, while small in acreage, represent a massive chunk of the human beings living in this country.

The Urban-Rural Divide is the Real Map

If we really wanted an accurate map, we’d stop coloring by state and start coloring by precinct. When you do that, the "United States" looks less like two separate countries and more like a fractal.

Even in the deepest red states, the state capital or the college town is a bright blue dot. In the deepest blue states, the farming communities are bright red. We aren't a country of Red States and Blue States; we are a country of Blue Cities and Red Countryside. The "state" level is just an administrative boundary that forces us into these two categories.

💡 You might also like: Why the Recent Snowfall Western New York State Emergency Was Different

Beyond the Binary: What’s Changing in 2026 and Beyond

Things are shifting. Fast.

Look at the Sun Belt. States like Georgia and North Carolina are seeing massive influxes of young professionals and tech workers. This is diluting the traditional conservative base. Meanwhile, in the North, some traditionally blue-collar Democratic strongholds are trending red as the parties realign around cultural issues rather than just economic ones.

- Demographic Shifts: Hispanic voters are not a monolith. In South Texas and parts of Florida, there has been a noticeable shift toward the Republican party.

- Education Gap: The biggest predictor of how you'll vote today isn't necessarily your income; it's whether or not you have a four-year college degree.

- Migration: People are moving from high-cost blue states like California and New York to lower-cost states like Texas and Florida. Whether they "bring their politics with them" or change their views once they arrive is the billion-dollar question for campaign managers.

Actionable Insights for Reading the Map

When you look at the map of US blue and red states during the next election cycle, don't just take it at face value.

- Check the "Margins," not just the colors. A state that is 51/49 is a "purple" state, even if the map renders it as solid red or blue.

- Look at the county-level data. See where the votes are actually coming from. Is it one big city carrying the whole state? Or is the support spread out?

- Follow the "Trendlines." Is a state becoming more red or more blue over the last three cycles? That's more important than who won it this year.

- Ignore the "Land Area" argument. Remember that empty acres in Wyoming don't vote, but people in high-rise apartments in Brooklyn do.

The map is a tool, but it's also a mask. It hides the complexity of a 340-million-person nation and tries to jam it into a simple, two-toned box. Understanding the nuances behind the colors is the only way to actually understand where the country is headed.

Stop looking at the colors and start looking at the people. That’s where the real story is.

To stay informed, always cross-reference geographic maps with population-weighted cartograms and precinct-level data provided by non-partisan sources like the MIT Election Data and Science Lab or the University of Virginia Center for Politics. This provides a clearer picture of the shifting American electorate and moves beyond the simplistic "red vs. blue" narrative.