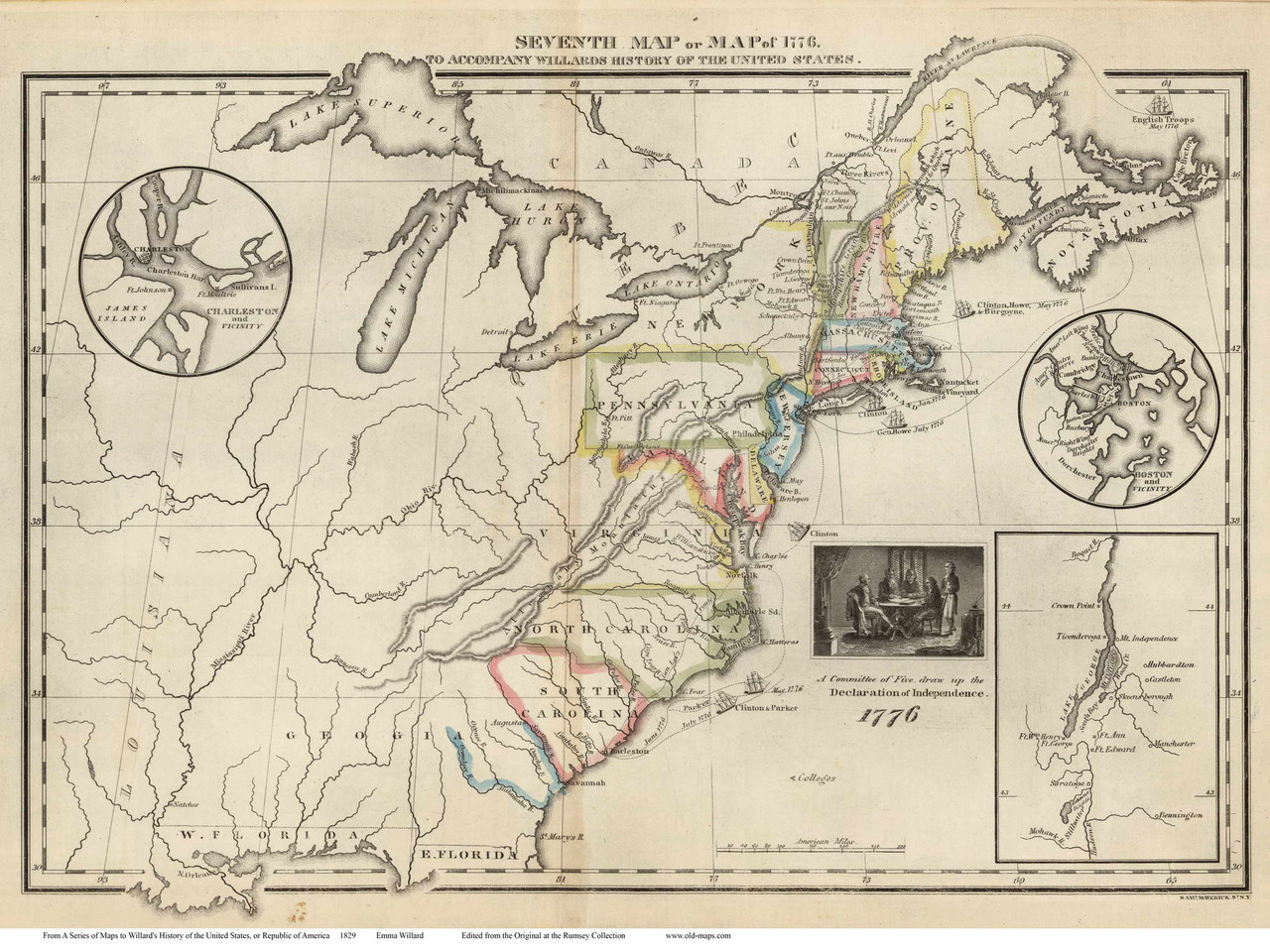

If you look at a map of the US 1776, you won't see that familiar "sea to shining sea" silhouette we all memorized in third grade. Honestly, it’s a mess. A beautiful, chaotic, confusing mess of overlapping land claims, indigenous territories, and European imperial posturing.

Most people imagine the thirteen colonies as neat little boxes hugging the Atlantic. That's a myth. In reality, the 1776 map was a political battleground before the first shot was even fired at Lexington and Concord. It was a projection of power, not a reflection of reality.

The Ghost of the Royal Proclamation

Back in 1763, King George III did something that absolutely infuriated the American colonists. He drew a line. It's called the Proclamation Line, and it basically followed the spine of the Appalachian Mountains.

The King told the colonists they couldn't settle west of that line. Why? Because the British Crown was broke after the Seven Years' War and didn't want to pay for more frontier conflicts with Native American tribes like the Cherokee or the Iroquois Confederacy.

But here’s the kicker.

Many colonial charters—like those of Virginia and Connecticut—specifically stated their borders went all the way to the "South Sea" (the Pacific Ocean). You’ve got a king saying "stop here" and a legal document saying "keep going." By the time we get to 1776, the map is a legal nightmare. Virginia technically claimed a massive chunk of what is now the Midwest, including Kentucky, Ohio, and even parts of Illinois.

The Colonies Weren't Just Thirteens

We talk about the "Thirteen Colonies" like they were the only game in town. They weren't. If you look at an actual British admiralty map from the era, you’ll see East Florida and West Florida.

Florida was British in 1776.

The British had picked it up from Spain in 1763. Interestingly, the Floridas didn't join the rebellion. They stayed loyal to the Crown. So, while Georgia was revolting, its southern neighbor was a British stronghold. If you were a British cartographer in 1776, your map of North America included a very loyal, very strategic Florida that most modern Americans completely forget about.

Then there’s Vermont. Or, well, the lack of it.

✨ Don't miss: How Long Ago Did the Titanic Sink? The Real Timeline of History's Most Famous Shipwreck

On a 1776 map, Vermont doesn't exist as a separate entity. It was a "disputed zone" between New York and New Hampshire. The "Green Mountain Boys" weren't just fighting the British; they were fighting New York surveyors who tried to take their land. It was a map of internal friction.

The Myth of Empty Space

Look at the western half of a 1776 map. It’s often labeled "Terra Incognita" or "Parts Unknown."

That is incredibly misleading.

Just because British or French mapmakers hadn't surveyed it doesn't mean it was empty. It was a densely populated landscape of sovereign nations. The Comanche Empire (Comancheria) was beginning its rise in the Southern Plains. The Lakota were moving into the Black Hills. To the west, the Spanish had a string of missions and presidios in California and New Mexico.

The map of the US 1776 that we see in history books is an Anglo-centric view. It ignores the Sioux, the Apache, and the Nez Perce who had their own territorial boundaries, trade routes, and "maps" that were often oral or based on geographical landmarks rather than ink on parchment.

Famous Maps of the Era: The Mitchell Map

If you want to know what George Washington or Benjamin Franklin were looking at, you have to look at the Mitchell Map.

John Mitchell, a botanist of all things, created this map in 1755. It remained the most detailed map of North America throughout the Revolutionary War. It’s huge. It’s detailed. And it’s full of mistakes.

The Mitchell Map famously misplaced the source of the Mississippi River. This single geographical error caused border disputes between the US and British Canada that lasted for decades. It also showed the "Sea of the West," a hopeful but non-existent body of water that people thought would lead straight to Asia.

Cartography in 1776 was as much about wishful thinking as it was about science.

🔗 Read more: Why the Newport Back Bay Science Center is the Best Kept Secret in Orange County

Why the 1776 Borders Look Like "Ladders"

Have you ever noticed how some of the northern colonies look like long, thin strips on old maps?

That's because of the "Sea-to-Sea" clauses.

Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania all had overlapping claims. Connecticut actually claimed a strip of land that ran through northern Pennsylvania. This led to the Pennamite-Yankee Wars, where settlers from Connecticut and Pennsylvania literally fought battles over who owned the Wyoming Valley.

Imagine living in a world where two different states claim your farm, and both send tax collectors. That was the reality of the 1776 map. It wasn't a static image; it was a series of conflicting layers.

The Forgotten "Fourteenth" Colony

There was actually a push to make a fourteenth colony called Transylvania.

No, not the vampire one.

Richard Henderson, a land speculator, tried to buy a massive tract of land from the Cherokee in what is now Kentucky. In 1775 and early 1776, Transylvania had its own assembly and its own laws. It was an illegal colony according to the British, and Virginia hated it because it sat on "their" land.

By the end of 1776, Virginia had asserted its authority and turned Transylvania into Kentucky County. But for a brief moment, the map of the US almost had a very different look.

The Role of the French and Spanish

We can't talk about 1776 without talking about the "Big Three" empires.

💡 You might also like: Flights from San Diego to New Jersey: What Most People Get Wrong

- Britain: Controlled the coast and the northeast.

- Spain: Controlled everything west of the Mississippi (Louisiana Territory) and Florida (though they'd temporarily traded it).

- France: Technically "out" of North America after 1763, but their influence remained in the culture, the trade routes, and the secret shipments of gunpowder they started sending to the rebels in 1776.

The map was a chess board. The American Revolution wasn't just a local civil war; it was a piece of a global conflict. When you look at the 1776 map, you're looking at the start of a massive real estate flip.

Practical Insights for History Buffs and Travelers

If you’re interested in seeing the remnants of this 1776 geography today, don’t just look at state lines. Look at the land.

- Visit the Cumberland Gap: This was the "gate" in the Proclamation Line. It's where the map literally broke open as settlers like Daniel Boone defied the King.

- Check out the Mason-Dixon Line: Surveyed just before the Revolution (1763–1767), it’s more than just a North/South divider; it was a high-tech feat of 18th-century cartography meant to settle a border war between the Penns and the Calverts.

- Study the "Western Reserve": In Ohio, you’ll find towns that look like they belong in New England. That’s because Connecticut held onto its 1776 claims in Ohio long after the war ended.

How to Read a 1776 Map Like a Pro

When you find a reproduction of a 1776 map—maybe at the Library of Congress digital archives—don't just look for the names of states. Look for the "notes."

Mapmakers back then loved to write little snippets of gossip or warnings. You’ll see things like "Abounding in Beaver" or "Great Desert." These notes tell you what the mapmakers valued: resources and survival.

They also frequently used the word "Nation" to describe indigenous groups, a linguistic acknowledgement of sovereignty that would tragically disappear from American maps in the 19th century.

Moving Beyond the Paper

The map of the US 1776 is a snapshot of an unfinished project. It represents a moment when the future was completely uncertain. Would there be one nation? Three? Fourteen? Would the British hold the South? Would the Spanish move east?

To truly understand the American Revolution, you have to stop seeing the 50 states and start seeing the messy, overlapping, and often illegal claims of 1776.

Next Steps for Deep Diving:

- Access the David Rumsey Map Collection: This is the gold standard for high-resolution historical maps. Search for "Mitchell Map 1755" or "Faden 1777" to see what the generals were actually using.

- Examine Colonial Charters: Read the actual text of the Virginia or Connecticut charters. It’s wild to see how "sea to sea" was written into law.

- Visit Historical Societies: If you’re in one of the original thirteen, their local archives often hold hand-drawn township maps from 1776 that show exactly who owned what tree and what creek.

The real map of 1776 isn't in a textbook. It’s in the overlapping stories of the people who tried to draw lines in the dirt while the world was on fire.