When you look at a modern map of the promised land Joshua and the Israelites supposedly conquered, it looks clean. There are neat lines. Different colors define the territories of the twelve tribes—Reuben, Gad, Manasseh, and the rest. But honestly? That’s not how it actually looked on the ground. Not even close. If you’ve ever tried to piece together the descriptions in the Book of Joshua, you’ve probably realized it reads more like a property deed written by someone who was halfway through a very long hike. It’s dense, it’s geographical, and it’s surprisingly messy.

The reality of the Conquest wasn't a total "sweep." It was a patchwork.

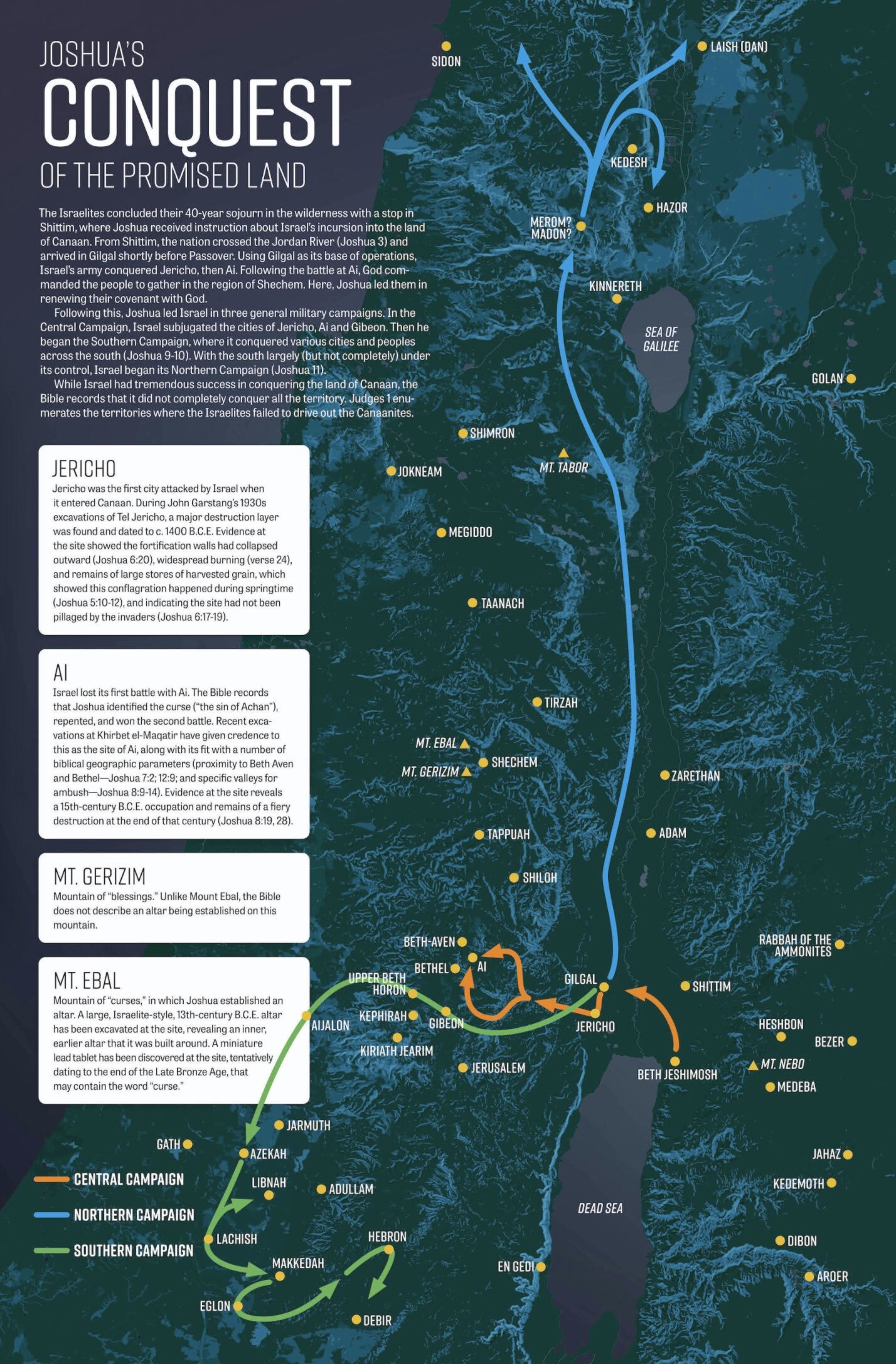

Joshua 13 through 19 contains what scholars often call the "Domesday Book" of the Bible. It's a massive list of borders, streams, mountain peaks, and tiny villages that don't exist anymore. To understand the map of the promised land Joshua describes, you have to look past the Sunday School version where the walls of Jericho fall and everything just becomes Israel overnight. The text itself admits that "very much land remains to be possessed." That's a huge detail. It means the map was more of a blueprint or a goal than a finished reality.

Why the Borders Don't Make Sense at First Glance

The geography of the Southern Levant is a nightmare for cartographers. You have the Great Rift Valley, the central highlands, and the coastal plains. When the distribution of land happened at Gilgal and later at Shiloh, the boundaries were defined by natural landmarks.

Think about it. There were no GPS coordinates. They used things like "the ascent of Adummim" or "the waters of En-shemesh." If a river dried up or a landmark was destroyed in a later war, the map changed. This is why when you look at different historical atlases, the borders of Benjamin or Dan seem to shift slightly.

The tribe of Judah got the lion's share of the south, but they had a problem: the Philistines. On almost any map of the promised land Joshua supposedly secured, the coastal plain is often shaded as Israelite territory. In reality? The Israelites struggled to hold the lowlands because the Canaanites had iron chariots. It’s like trying to fight a tank with a stick. They stayed in the hills. So, the "map" you see in many Bibles is often an "idealized" version of what was intended, rather than what was strictly occupied in 1200 BCE.

The Transjordan Twist

Most people forget the map starts outside the Promised Land. Reuben, Gad, and half of Manasseh looked at the rolling hills of Gilead and Bashan (modern-day Jordan) and said, "Yeah, this works for our cows."

📖 Related: Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen Menu: Why You’re Probably Ordering Wrong

Moses agreed, but with a catch. They had to cross the river and fight for the west side before they could settle the east. This created a permanent geographical split. The Jordan River became more than a border; it became a psychological barrier. When you see a map of the promised land Joshua oversaw, that eastern slice is vital. Without it, you’re missing nearly a third of the tribal allotments. It also explains why those tribes were often the first to be raided by desert nomads—they were the buffer zone.

Mapping the "Unconquered" Areas

One of the most fascinating things about the Book of Joshua is that it lists its own failures. This is great for historical E-E-A-T (Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, and Trustworthiness) because it shows the text isn't just propaganda. It’s messy.

Take Jerusalem.

The map of the promised land Joshua describes technically puts Jerusalem on the border between Judah and Benjamin. But the text explicitly says the Benjaminites could not drive out the Jebusites. Jerusalem remained a foreign enclave right in the heart of the country for centuries until David showed up.

Then you have the Phoenician coast. The tribe of Asher was allotted the area around Tyre and Sidon. Did they ever really control it? Not really. They mostly lived among the Canaanites. When we draw these maps today, we tend to use solid colors. A more accurate map would use dots or gradients to show where Israelite influence was strong and where it was basically non-existent.

The Problem with Dan

The tribe of Dan had the worst luck. Their original spot on the map was squeezed between the powerful Philistines and the mountains. It was too small. Eventually, they gave up and migrated all the way to the far north, near the foot of Mount Hermon.

👉 See also: 100 Biggest Cities in the US: Why the Map You Know is Wrong

If you look at a map of the promised land Joshua established, you’ll sometimes see Dan in two places. This tells a story of migration and survival that a simple list of names can't convey. It’s a reminder that these borders were fluid. People moved. Wars happened. Droughts forced families to find better soil.

The Theology of the Map

Why does the Bible spend so many chapters describing borders? It’s boring to read, honestly. But for the original audience, the map was a legal document. It was proof of inheritance.

In the ancient Near East, land was everything. If you didn't have land, you didn't have a name. By mapping out the territory, the author of Joshua was asserting a claim. Even if they hadn't kicked out every local king yet, the map served as a "statement of intent."

Levi’s Missing Territory

You won't find a "State of Levi" on a map of the promised land Joshua divided. The Levites didn't get a block of land. Instead, they got 48 cities scattered throughout the other tribes.

This was a genius move for national unity. By placing the priests in every region—Hebron in the south, Shechem in the center, Kedesh in the north—the map ensured that the religious and legal "glue" of the nation was everywhere. They also established "Cities of Refuge." These were specific spots on the map where someone who accidentally killed someone could flee to avoid blood vengeance. Geography was used to administer justice.

Modern Archaeology and the Joshua Map

Archaeologists like Israel Finkelstein and the late Adam Zertal have spent decades arguing over how much of this map matches the "destruction layers" found in the ground.

✨ Don't miss: Cooper City FL Zip Codes: What Moving Here Is Actually Like

There's a lot of debate.

Some sites, like Hazor, show a massive burn layer that fits the timeline of Joshua’s northern campaign perfectly. Others, like Ai or Jericho, have been harder to pin down. Some scholars suggest the map of the promised land Joshua describes reflects the boundaries during the time of King Josiah (7th Century BCE) rather than the 13th Century BCE.

Regardless of the specific century, the topographical accuracy is wild. The writer knew the "way of the wilderness," the "ascent of Lebonah," and the "valley of Achor." You can take a modern topographical map of Israel/Palestine today and trace these paths. The geography is real, even if the political control was complicated.

Tips for Visualizing the Tribal Allotments

If you're trying to study this, don't just look at a flat 2D map. Use Google Earth. Look at the elevation.

- Judah: Rugged wilderness and high hills. Perfect for defense.

- Ephraim/Manasseh: The "breadbasket" with fertile valleys. This is why they became so powerful and eventually led the Northern Kingdom.

- Zebulun and Issachar: Tucked into the Jezreel Valley, the most strategic highway of the ancient world.

- The Coastal Plain: Wide, flat, and dangerous.

The map of the promised land Joshua left us is essentially a guide to how terrain dictates destiny. The tribes in the mountains stayed "purer" in their culture because they were isolated. The tribes on the coast or the valley floors were constantly influenced by trade and foreign armies.

How to Actually Use This Information

If you are a student of history or theology, don't get hung up on the "perfect" borders. They didn't exist. Instead, focus on the "hubs."

- Identify the cultic centers: Places like Shiloh (where the Tabernacle sat) and Shechem (where the covenant was renewed) are the anchors of the map.

- Look for the gaps: Notice the areas the text says they couldn't take. That's where the future stories of the Judges and Saul and David come from.

- Check the water: Every major boundary on the map of the promised land Joshua defined follows a wadi (dry riverbed) or a perennial stream. Water was life. If you find the water, you find the border.

- Acknowledge the overlap: Many cities are listed for two different tribes. This isn't necessarily a mistake; it's a sign of shared jurisdiction or shifting populations.

The map is a living thing. It’s a record of a nomadic people trying to become a landed people. It’s gritty, it’s specific, and it’s deeply tied to the dirt and rocks of the Levant. When you stop looking for a perfect political map and start looking for a survival guide, the Book of Joshua suddenly makes a lot more sense.

The next step for anyone interested in this period is to look at the transition into the period of the Judges. The map stays the same, but the "solid colors" of the tribes begin to bleed into the surrounding Canaanite cultures. To see the reality of the map, you have to look at the archaeological survey of the Manasseh hill country, which shows a massive explosion of small, new villages in the exact timeframe the Bible describes. That is the real map—one village, one cistern, and one terrace at a time.