William Golding wasn't just writing a story about kids killing each other; he was building a trap. When you look at a map of the island from Lord of the Flies, it looks like a paradise. Palm trees. Pink granite. Shimmering lagoons. But if you actually track the movements of Ralph, Piggy, and Jack, you realize the geography is a psychological weapon. It’s shaped like a boat, which is a cruel irony for a group of boys who are utterly stranded.

The island is a character. Honestly, it’s probably the most consistent character in the book because it never changes while the boys descend into total madness.

Why the Boat Shape Matters

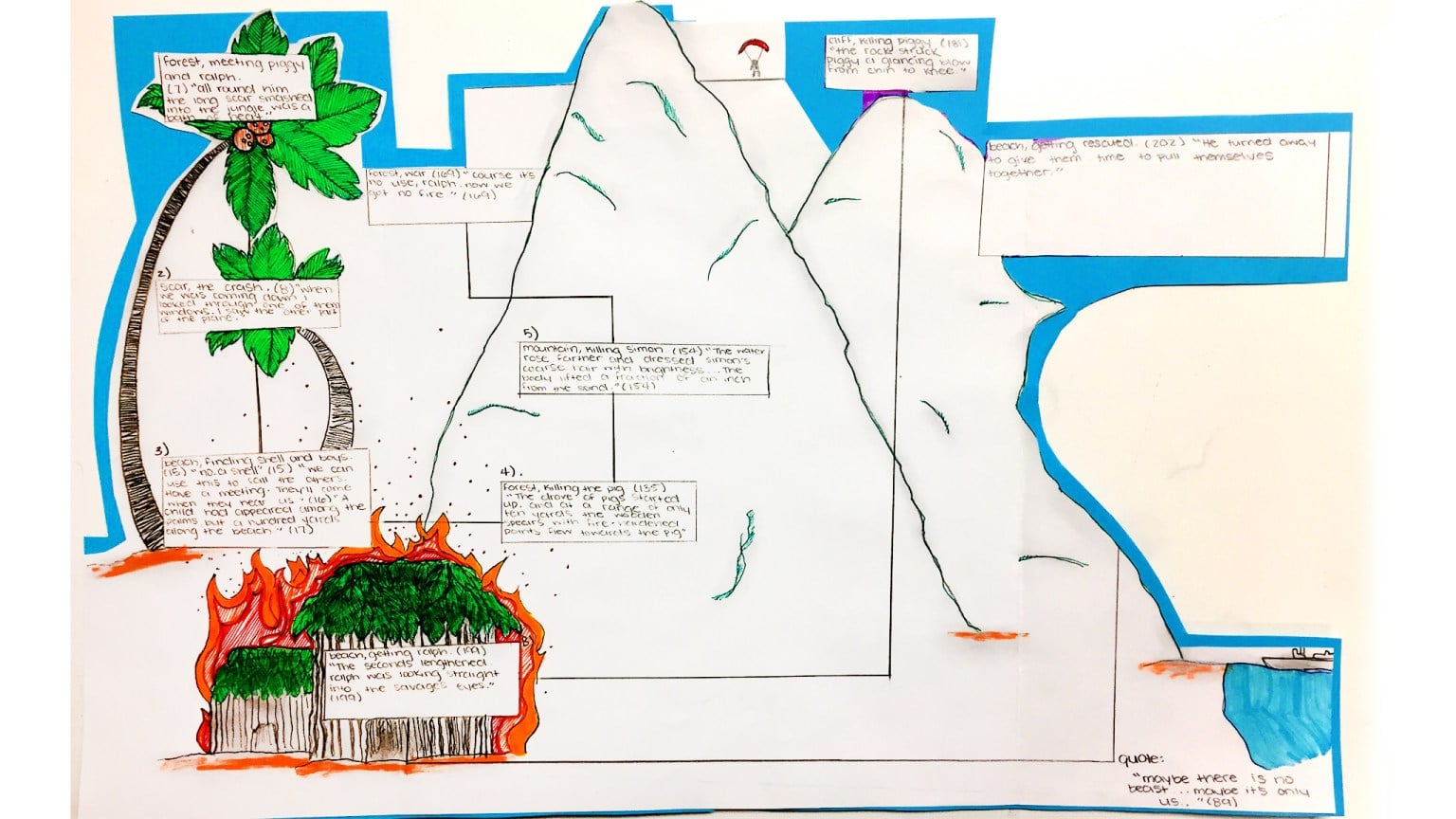

Most people think the island is just a random patch of dirt in the Pacific. It isn't. Golding describes it as "boat-shaped," with a high peak at one end and a rocky tail at the other. This isn't just a fun fact for your next trivia night. It’s a literal metaphor for their situation. They are on a ship that isn't going anywhere.

At the "stern" of this geological ship, you’ve got the Castle Rock. That’s where Jack eventually sets up his fortress of doom. Then there’s the "bow," where the mountain stands. In the middle? That's the scar. The scar is where the plane crashed, ripping through the jungle and creating a literal wound in the earth. It’s a messy, jagged line of destruction that marks the beginning of their stay.

The Layout of the Jungle

The jungle is thick. It’s hot. It’s claustrophobic. Golding uses specific terms like "entangling creepers" and "shimmering heat haze" to make you feel the weight of the humidity. You have the platform near the bathing pool—that’s the center of democracy. It’s where the conch rules. But as you move away from the platform toward the mountain or the thickets, the rules start to blur.

✨ Don't miss: Austin & Ally Maddie Ziegler Episode: What Really Happened in Homework & Hidden Talents

You’ve got the fruit trees where the littlunes spend most of their time getting diarrhea and crying. Then there’s the "closed place" where Simon goes to be alone. It's a sanctuary, but even that gets tainted when the pig's head on a stick—the Lord of the Flies—is planted there. Geography reflects morality here.

The Deadly Geometry of Castle Rock

If the platform represents the head and the heart, Castle Rock is the gut. It’s a massive hunk of pinkish stone connected to the main island by a narrow neck of land. This is a tactical nightmare. From a military perspective, it’s a perfect fortress. Jack knows this. Ralph doesn't care because he’s too busy thinking about smoke signals.

When you look at a map of the island from Lord of the Flies, Castle Rock stands out because it’s barren. No fruit. No easy water. Just stone and height. It’s where Piggy dies. It’s where the boulder is pushed. The geography here is vertical—the higher up Jack’s tribe goes, the more "elevated" they feel in their power, but the further they are from the grounded reality of the beach.

Water as a Barrier and a Grave

The lagoon is protected by a coral reef. Inside, it’s calm. Outside? The Pacific is a "vastness." Golding spends a lot of time describing the tide. It’s the tide that takes Simon’s body. It’s the tide that carries Piggy away. The water isn't just a place to swim; it's a cleaning crew that wipes away the evidence of the boys' sins.

🔗 Read more: Kiss My Eyes and Lay Me to Sleep: The Dark Folklore of a Viral Lullaby

The beach is thin. It’s a narrow strip of safety between the dark, scary jungle and the infinite, terrifying ocean. When the boys start moving their fires from the mountain down to the beach, they are literally shrinking their world. They’re giving up on the high ground—the place where they could see the horizon—and huddling in the sand.

Mapping the Descent into Savagery

You can actually track the plot by following the movement across the terrain.

- The Crash: The Scar.

- The Assembly: The Platform.

- The Search for the Beast: The Mountain.

- The Schism: The move to Castle Rock.

- The Final Hunt: The entire island is set on fire.

The mountain is the highest point, and it’s where the "beast" (the dead parachutist) lands. This is crucial because the boys' fear is physically located above them. They have to look up to see their nightmare. But the real beast is inside them, which Simon realizes in the middle of the jungle. The map of the island from Lord of the Flies is a map of a descent. They start high at the mountain and end up crawling through the undergrowth like animals at the end.

The Illusion of the Mirage

Golding mentions the mirages a lot. At midday, the island "flickers" and changes shape. This makes the map unreliable. Is that a boat on the horizon? Or just a trick of the light? The boys can’t trust their eyes, which means they can’t trust the land. This geographical instability leads to mental instability.

💡 You might also like: Kate Moss Family Guy: What Most People Get Wrong About That Cutaway

Real-World Comparisons

Golding based the island on his experiences in the Royal Navy during WWII and his time as a schoolteacher. He knew how isolation worked. Many scholars compare the island to Coral Island by R.M. Ballantyne, which was a much more "cheery" version of the same story. In Ballantyne’s world, the island is a resource. In Golding’s world, the island is a mirror. It shows the boys who they really are.

Interestingly, there is a real-life case of shipwrecked boys—the "Tongan Castaways" of 1965. Six boys were stranded on the island of 'Ata for 15 months. Unlike Golding’s characters, they actually worked together, set up a garden, and kept a fire going the whole time. They were rescued by an Australian sea captain. This shows that Golding’s map was a specifically designed "worst-case scenario" geography. He built a pressure cooker.

Visualizing the Scale

The island isn't huge. You can walk across it in a day. This proximity is what causes the friction. You can’t escape Jack. You can’t hide from the choir. The smallness of the map of the island from Lord of the Flies is what makes the tension so high. If the island were the size of Australia, the boys would have just stayed away from each other and been fine.

The Final Destruction

By the end of the book, the map is gone. The forest is burned. The fruit trees are scorched. The "boat" is on fire. When the naval officer arrives, he sees a smoldering wreck. The boys didn't just break the rules; they broke the land.

To truly understand the story, you need to look at the terrain as more than just a background. It’s a guide to the character's souls.

Actionable Insights for Students and Readers:

- Trace the Path of the Conch: Follow where the conch is held versus where it is destroyed. Its physical location on the map usually marks the current "capital" of the boys' society.

- Analyze the Verticality: Note how the boys move from the beach (low) to the mountain (high) and back down to the "fortress" of Castle Rock. High ground usually represents a search for truth or power, while low ground is survival.

- Compare the "Scar" to the "Sanctuary": Look at Simon's hidden spot versus the crash site. One is nature untouched; the other is nature ruined by human arrival.

- Identify the Micro-Climates: Notice how the heat is described differently on the mountain versus in the thicket. Golding uses temperature to signal when a character is about to snap.