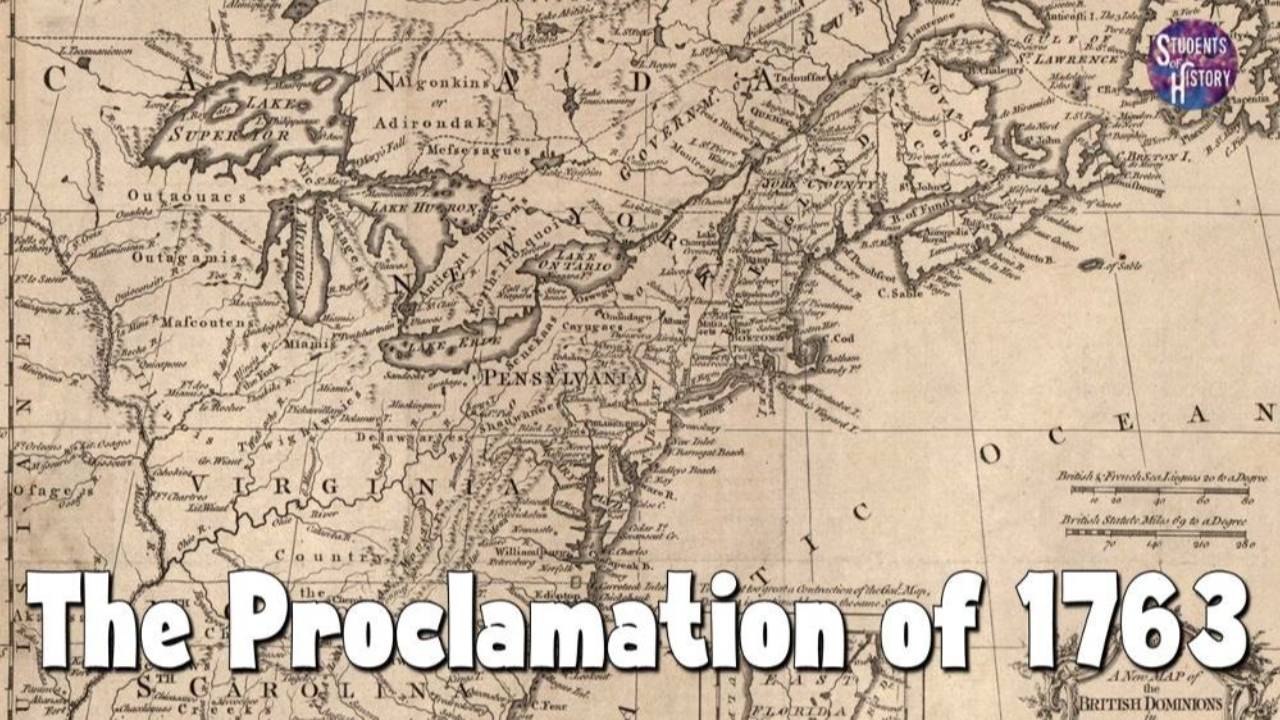

If you look at a map of Proclamation of 1763, you’ll see a jagged, crimson line snaking right down the spine of the Appalachian Mountains. It looks like a simple boundary. It wasn't. Honestly, it was more like a "keep out" sign posted on a neighbor's front lawn after you’ve already spent years helping them build their house. King George III basically told the American colonists that the vast, fertile lands they just bled for during the Seven Years' War were strictly off-limits.

It was a shock.

For the average settler in 1763, this wasn't just about geography or cartography. It was about survival and the promise of wealth. They had just finished fighting the French and Indian War alongside the British Redcoats. The French were gone. The Ohio River Valley was finally open. Or so they thought. Instead, the Crown issued a royal decree that felt like a slap in the face.

What the Map of Proclamation of 1763 Actually Showed

When you study the original hand-drawn maps from the 18th century, you see the "Proclamation Line" running from the Atlantic Ocean's watershed in the north all the way down to West Florida. It wasn't a random choice. The British used the crest of the Appalachians as a natural divider. Everything to the east was for the colonies. Everything to the west? Reserved for the Indigenous tribes.

The British logic was kinda simple: they were broke.

Wars are expensive. Like, devastatingly expensive. The British National Debt had nearly doubled during the conflict with France, reaching about £133 million by 1763. Maintaining peace between encroaching settlers and Native American confederacies required troops. Troops cost money the Crown didn't have. By drawing this line on the map of Proclamation of 1763, King George III hoped to prevent expensive frontier wars like Pontiac’s Rebellion, which had already seen several British forts fall.

🔗 Read more: Lake Nyos Cameroon 1986: What Really Happened During the Silent Killer’s Release

A Boundary Made of Paper, Not Stone

The line was never meant to be a permanent wall. It was supposed to be a temporary "breather" to let things cool down. But try telling that to a land speculator like George Washington. Yes, even the future first president was annoyed. He and his partners in the Ohio Company had invested heavily in western land claims. To them, the map was a barrier to their financial future.

There’s a common misconception that the line was just about protecting Native American rights. While the Proclamation of 1763 did recognize Indigenous title to the land—a legal precedent that still echoes in Canadian and American law today—the primary motivation was administrative control. The British wanted the colonists huddled on the coast where they were easier to tax and govern. If they scattered into the wilderness, they became "lawless" and hard to manage.

The Geographic Reality vs. The Colonial Dream

Imagine you’re a farmer in Virginia in 1764. Your soil is exhausted from decades of tobacco farming. You need new land. You look west and see the blue-misted peaks of the mountains. You know there is rich, black soil on the other side. Then, a British official pulls out a map of Proclamation of 1763 and tells you that if you cross that ridge, you’re a criminal.

It didn't sit well.

- The Northern Section: The line cut through New York and Pennsylvania, blocking access to the Great Lakes.

- The Central Section: This was the real heart of the conflict. The Ohio Valley was the "American Dream" of the 1760s.

- The Southern Section: It impacted the Carolinas and Georgia, limiting their expansion into what is now Alabama and Mississippi.

The geography was absolute, but the enforcement was impossible. The British had about 10,000 troops stationed in North America. Sounds like a lot, right? It wasn't. Not when you're trying to police a mountain range that stretches over 1,500 miles. People just... went anyway. They were called "squatters," but they saw themselves as pioneers.

💡 You might also like: Why Fox Has a Problem: The Identity Crisis at the Top of Cable News

Why the Map Looked the Way It Did

Cartographers of the era, like John Mitchell, had created incredibly detailed maps (like the Mitchell Map of 1755) that were used to negotiate these boundaries. When you look at these documents, you see how much "empty" space there appeared to be. Of course, it wasn't empty. It was home to the Shawnee, the Cherokee, the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), and dozens of other nations.

The Proclamation was actually the first time in European law that Indigenous land rights were formally codified. It stated that only the Crown could purchase land from Native tribes. Private citizens couldn't just walk up and "buy" a forest for a bottle of rum. This was a massive shift. It centralized power. It also meant the Crown became the ultimate "real estate agent" for the continent.

The Resentment That Led to Revolution

Historians like Colin Calloway have argued that the Proclamation was perhaps the single most important factor in alienating the colonies. We often talk about "No Taxation Without Representation" and the Stamp Act. Those were huge. But the map of Proclamation of 1763 hit a different nerve. It hit the "land hunger."

In the 18th century, land was the only way to move up in the world. If you didn't own land, you didn't have a vote. You didn't have status. By freezing the borders, the King was essentially freezing the social hierarchy of the colonies.

The Great Defiance

Did the map stop people? Hardly.

📖 Related: The CIA Stars on the Wall: What the Memorial Really Represents

Daniel Boone is the classic example. A few years after the Proclamation, he was already pushing through the Cumberland Gap. The "Wilderness Road" became a literal bypass of the King’s law. By 1774, the line was basically a joke on the ground, even if it was still a legal reality in London.

The British tried to tighten the screws with the Quebec Act of 1774. This took the land north of the Ohio River—land the Virginians claimed—and handed it to the province of Quebec. If the 1763 map was a "keep out" sign, the 1774 map was the King giving your backyard to your rival. This was one of the "Intolerable Acts" that pushed the colonies to the breaking point.

Looking at the Map Through Modern Eyes

When we look at a map of Proclamation of 1763 today, we’re looking at a blueprint for conflict. It represents a fundamental misunderstanding between a distant government and the people on the ground. The British saw a need for order and fiscal responsibility. The colonists saw a betrayal of their service and an infringement on their "natural rights."

It’s also a sobering reminder of the Indigenous experience. For the Native nations, the line was a fragile promise. It was a recognition of their sovereignty that was broken almost as soon as the ink dried. Once the American Revolution ended and the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783, that "red line" vanished. The new United States had no intention of keeping the settlers behind the mountains.

Misconceptions to Clear Up

- It wasn't a wall. There were no fences. It was a legal boundary enforced by occasional patrols and the threat of no legal protection if you got into trouble out west.

- It didn't just affect the poor. The wealthiest men in America—George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin—were all heavily involved in land speculation companies that were crippled by the Proclamation.

- It wasn't just about the French. While it happened after the French were defeated, the primary "threat" the British were managing was the cost of fighting Native Americans who were rightfully defending their homes.

Actionable Insights: How to Study the Map Today

If you want to truly understand the birth of the United States, you have to start with this map. It’s the "Point A" of the American Revolution.

- Visit the Source: Check out the digital archives of the Library of Congress. They have high-resolution scans of the original 1763 maps where you can see the actual annotations made by British officials.

- Overlay the Geography: Use modern tools like Google Earth to look at the Appalachian crest. When you see how rugged that terrain is, you realize how bold those early "illegal" settlers actually were.

- Trace the "Proclamation Line" Hiking Trail: In many parts of the Eastern US, you can actually hike along the ridges that formed the 1763 boundary. It gives you a physical sense of the barrier the King tried to impose.

- Read the Primary Text: Don't just look at the map; read the Royal Proclamation itself. It’s surprisingly short. Notice how many times it mentions "protection" of the "Indians." It’s a fascinating look at 18th-century diplomacy.

The map of Proclamation of 1763 isn't just a relic of the British Empire. It is the geographic record of a family argument that turned into a divorce. It defined where the "Old World" ended and the "American West" began. By understanding that line, you understand why the colonies finally decided they didn't want to be colonies anymore.

Start by finding a high-quality reproduction of the 1763 map and comparing it to a map of the colonies in 1776. The difference tells the whole story. You'll see the expansion, the defiance, and the beginning of a continental power.