You’ve probably seen the sketches in a middle school textbook. A winding line of ink cutting through a beige void, supposedly representing the "first" look at the American West. But honestly, the real story of the map of lewis and clark is a lot messier—and way more impressive—than the simplified version we usually hear. It wasn't just a drawing. It was a 1814 political weapon that basically told the world: "This land belongs to us now."

Before Meriwether Lewis and William Clark set off in 1804, Thomas Jefferson had some pretty wild ideas. He kind of expected them to find a "Passage to India," a simple water route where you could just hop over a small hill and find a river flowing to the Pacific.

Spoiler alert: That didn't happen.

Instead of a gentle stroll, they found the Bitterroot Mountains. They almost starved to death eating their own horses. The map that eventually came out of this ordeal didn't just show where they went; it shattered a hundred years of European "wishful thinking" geography.

The Map That Ended a Myth

For decades, geographers in Europe and the East Coast filled the western half of North America with whatever they wanted. They drew a single, lonely mountain range. They imagined "The River of the West." When William Clark finally sat down in St. Louis around 1810 to compile his field notes, he wasn't just drawing a trail. He was documenting a "tangle of mountains" that no one expected.

His masterwork, titled A Map of Lewis and Clark's Track, Across the Western Portion of North America, was eventually published in 1814. It was a massive team effort.

🔗 Read more: Why Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station is Much Weirder Than You Think

- William Clark provided the raw, gritty field sketches and the "master" drawing.

- Nicholas Biddle (who stepped in after Lewis’s tragic suicide) managed the text.

- Samuel Lewis, a Philadelphia cartographer, "cleaned up" the hand-drawn mess into something a printer could use.

- Samuel Harrison was the guy who actually engraved the copper plate that let them print copies.

One thing people often miss? This map wasn't just based on what the Corps of Discovery saw with their own eyes. Clark was a bit of a sponge for information. While he was in St. Louis serving as Superintendent of Indian Affairs, he kept updating his draft. He talked to fur trappers like Manuel Lisa and even John Colter, the guy who "discovered" Yellowstone (which most people thought was a lie at the time).

If a trapper came back from a new valley, Clark added it.

Indigenous Knowledge: The Secret Ingredient

We often talk about Clark like he was a solo genius, but he was basically crowdsourcing. A huge portion of the map of lewis and clark relies on "Indigenous Geographic Knowledge."

The Mandan leader Big White (Sheheke) and other tribal informants didn't just give directions; they drew maps in the dirt and on hides. Clark painstakingly transferred that info onto paper. He mapped out the Snake and Columbia rivers using details from Nez Perce and Shoshone guides who knew the terrain like the back of their hand.

Without them, the map would have been a series of "blanks" punctuated by a single thin line of the main trail. Instead, it showed a web of interconnected life.

💡 You might also like: Weather San Diego 92111: Why It’s Kinda Different From the Rest of the City

Science vs. Reality: How Accurate Was It?

You’d think a map made with a 19th-century octant and a wonky chronometer would be a disaster.

Actually, it’s kind of scary how good it was.

Modern scholars have georeferenced the 1814 map against satellite imagery. From their starting point at Camp Wood (River Dubois) to the Pacific, Clark was only off by about 40 miles. That’s insane. He used a chronometer to calculate longitude—a technology that was still relatively new for land travel.

But it wasn't perfect.

- The "High Plain" Error: They still thought the headwaters of the major rivers (the Missouri, Columbia, and Colorado) were much closer together than they actually were.

- The "Passage" Hangover: Even though they knew there was no easy water route, the map still hinted at a "short" portage that misled later travelers.

- Magnetic Declination: Their compasses were occasionally affected by local ore deposits, leading to slight "kinks" in the river bends.

The Missouri River meanders. A lot. Clark recorded the compass bearing for every single "reach" or bend of the river. When the Missouri River Commission checked his work 90 years later, they found his distances were remarkably consistent with their own measurements, at least in the rocky canyons where the river doesn't move much.

📖 Related: Weather Las Vegas NV Monthly: What Most People Get Wrong About the Desert Heat

Why This Map Still Matters Today

The map of lewis and clark did more than just guide fur traders. It paved the way for "Manifest Destiny." Once there was a map, there was a plan. Once there was a plan, there was an invasion.

For the United States, it was the birth of a continental empire. For the Indigenous nations whose villages are meticulously marked on the 1814 engraving, it was the beginning of a era of forced removal and broken treaties. It’s a heavy piece of paper.

If you want to see the real deal, the original copper printing plate is actually at the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. Most of the 83 original manuscript maps Clark drew in the field? Those are tucked away in the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale.

Actionable Ways to Explore the Map Yourself

You don't have to be a historian to geek out on this.

- Check the Digital Archives: Don't just look at a low-res JPG. The David Rumsey Map Collection has a high-definition scan of the 1814 Samuel Lewis engraving. You can zoom in until you see the individual dots for Mandan villages.

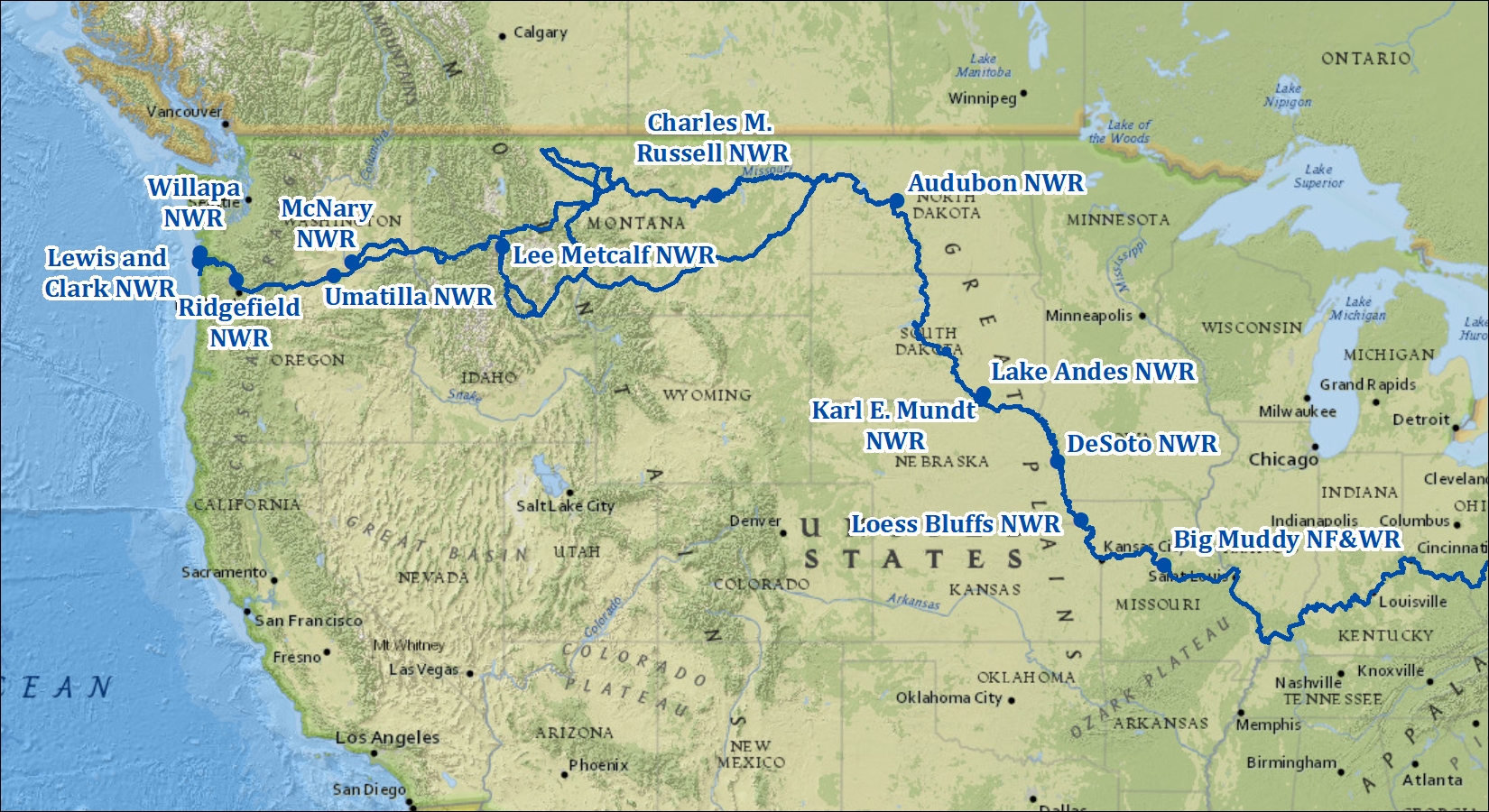

- Visit the Trail: If you're ever in Omaha, Nebraska, the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail Headquarters has a massive visitor center. They use modern GPS "commemorative markers" to show exactly where the expedition's measurements match up with the ground today.

- Compare with Google Earth: Take a screenshot of the 1814 map's depiction of the "Great Falls" in Montana and overlay it on a modern satellite view. It’s a trip to see how the dams have changed the landscape while the "skeleton" of the river Clark drew remains the same.

The map of lewis and clark wasn't just a record of where two guys walked. It was the moment the "empty" space on the American map became a complex, crowded, and contested reality. It's a reminder that geography is never just about dirt and water—it's about who gets to draw the lines.