Henry Hudson didn't actually know where he was going. That sounds harsh, doesn't it? But if you look at a map of henry hudson voyages, you aren't looking at a master plan of discovery; you're looking at a series of desperate, cold, and often dangerous pivots. He was a man obsessed with a shortcut that didn't exist. Between 1607 and 1611, Hudson made four major journeys, and honestly, he failed at his primary goal every single time. He wanted the North Pole or the Northwest Passage. He found ice, mutiny, and a very famous river instead.

Most history textbooks gloss over the messy parts. They show a clean line curving from England or the Netherlands across the Atlantic. But the reality recorded in the logs of the Hopewell, the Half Moon, and the Discovery tells a story of a captain who frequently ignored his employers' orders. If his bosses at the Muscovy Company or the Dutch East India Company told him to go East, and he hit ice? He’d just turn West. No permission. No radio. Just a gut feeling and a crew that was increasingly terrified of freezing to death.

Mapping the Frigid Failures of 1607 and 1608

The first two legs of any map of henry hudson voyages focus on the "Northeast Passage." In 1607, Hudson took the Hopewell and tried to sail literally over the top of the world. He thought that because the sun shone 24 hours a day in the Arctic summer, the ice would melt at the Pole. It didn't. He reached the Svalbard archipelago and realized the "Open Polar Sea" was a myth.

The 1608 voyage was more of the same. He tried to get past Novaya Zemlya, an island chain in the Russian Arctic. He failed. Again. But these maps are crucial because they pushed him to stop looking East. He started listening to his friend Captain John Smith—yes, that John Smith—who sent him maps suggesting there might be a passage to the Pacific somewhere around 40 degrees north latitude in America.

The Half Moon and the Wrong Turn That Made History

1609 is the big one. This is the voyage everyone remembers. Hudson was working for the Dutch this time. His contract was strictly to find a route around the north of Russia. But when the ice blocked him again near the North Cape of Norway, he didn't go home to Amsterdam to explain himself. He turned the Half Moon around and sailed across the Atlantic.

💡 You might also like: Leonardo da Vinci Grave: The Messy Truth About Where the Genius Really Lies

When you trace this part of the map of henry hudson voyages, you see him hitting Newfoundland, then Maine, then Cape Cod. He eventually sailed into what we now call New York Harbor and up the river that bears his name. He made it as far as present-day Albany before the water got too shallow and fresh. He realized this wasn't the Pacific. It was just a really big river.

Why the 1609 Map Changed Everything

- The Fur Trade: Even though he didn't find China, he found beaver. Lots of them. This led directly to the Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam.

- Navigation Errors: Hudson’s charts of the Jersey shore and the mouth of the Hudson were surprisingly detailed for the time, though he still struggled with calculating precise longitude.

- Colonial Foundation: Without this "accidental" detour, the Dutch wouldn't have had a claim to the region, and New York might look very different today.

The Final Journey: A Map to a Dead End

Hudson’s last voyage in 1610-1611 is a tragedy. Sailing for the English again in the Discovery, he went much further north, entering the "Furious Overfall" (the Hudson Strait). If you look at this map of henry hudson voyages, it looks like he finally found it. He entered a massive body of water—Hudson Bay. It was so big he was certain he’d reached the Pacific.

He spent months exploring the southern coast of the bay, specifically James Bay. Then the ice trapped them. Winter in the Canadian subarctic is brutal. The crew was starving. They were eating lichen and whatever birds they could knock out of the sky. Hudson, by all accounts, was not a "people person." He was secretive and favored certain crew members. By June 1611, the ice broke, but instead of heading home, Hudson wanted to keep searching.

The crew had had enough.

📖 Related: Johnny's Reef on City Island: What People Get Wrong About the Bronx’s Iconic Seafood Spot

They set Hudson, his son John, and several loyal or sick crewmen adrift in a small boat with no motor, few supplies, and no hope. The Discovery sailed back to England. The men in the small boat were never seen again. When you look at the final dot on that map, it’s not a destination. It’s a disappearance.

Understanding the Cartography of the 17th Century

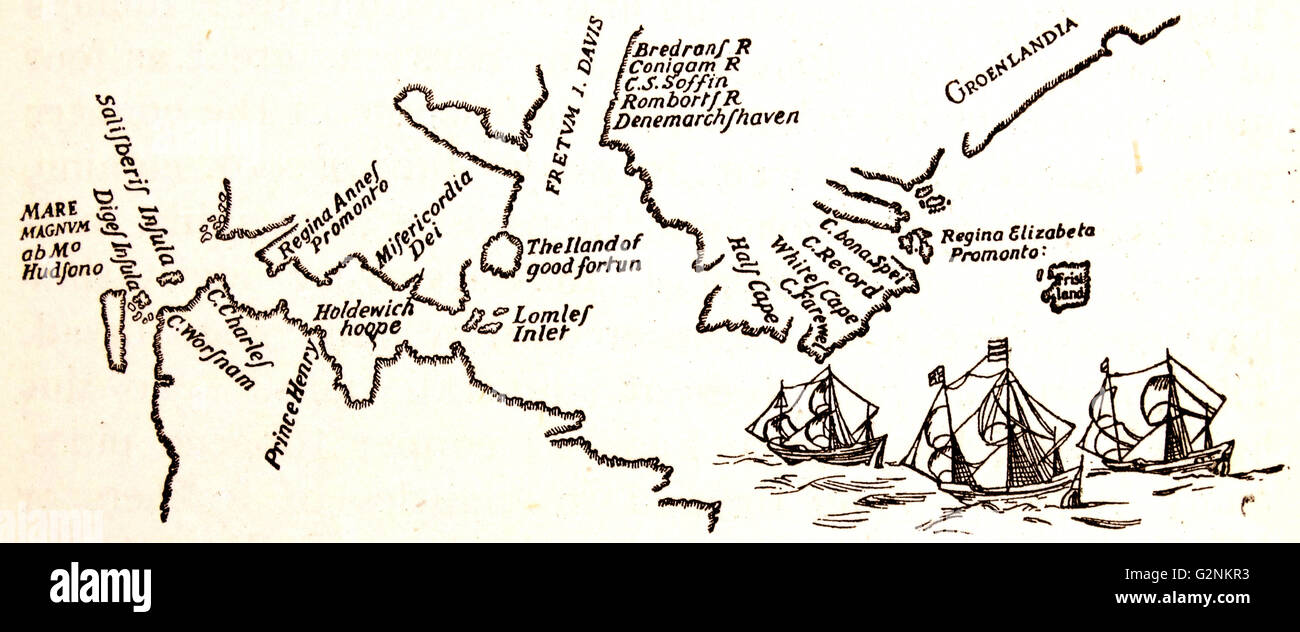

To truly read a map of henry hudson voyages, you have to understand that the maps he used were half-science and half-rumor. Cartographers like Petrus Plancius were giving Hudson maps that showed "Strait of Anian" where Alaska should be. They were guessing.

Hudson’s own contributions to the map were filtered through the men who betrayed him. Abacuk Pricket, one of the mutiny survivors, was the one who brought back the journals and notes. We only know what happened because the mutineers needed to tell a story that wouldn't get them hanged (though they were tried, most were acquitted because their navigational skills were too valuable to the Crown).

Navigational Tools of the Era

- The Backstaff: Used to measure the sun's altitude without staring directly at it.

- The Astrolabe: A bit old-school by 1610, but still used for stellar navigation.

- Dead Reckoning: Basically guessing speed and direction using a log line and a compass. This is why many of Hudson's mapped distances are slightly "off."

Why These Maps Still Matter

We don't look at a map of henry hudson voyages to find a way to China anymore. We look at them to see the beginning of the "Little Ice Age" impact on exploration. We look at them to understand the displacement of the Lenape and Cree peoples who had lived on those "discovered" shores for millennia. Hudson wasn't discovering "new" lands; he was mapping them for European markets.

👉 See also: Is Barceló Whale Lagoon Maldives Actually Worth the Trip to Ari Atoll?

His failure to find the Northwest Passage actually spurred others to map the entire Canadian Arctic. Every time Hudson hit a dead end, he forced the next guy to look a little further left or a little further right.

Actionable Insights for History Enthusiasts and Travelers

If you are interested in tracing these routes yourself, you don't need a wooden ship and a mutinous crew. You can actually visit the key landmarks that define the Hudson legacy.

- Visit the New York Historical Society: They hold incredible records and physical artifacts related to the 1609 voyage and the subsequent Dutch mapping of "New Netherland."

- Explore the Hudson River Valley: Take the Amtrak "Maple Leaf" or "Adirondack" lines. These tracks run right along the eastern bank of the river, providing the exact vantage point Hudson had from the Half Moon as he sailed toward Albany.

- Digital Mapping: Use the "Hudson's Voyage of 1609" interactive maps provided by various educational foundations (like the New Netherland Institute) to overlay his 1609 coordinates onto modern Google Earth data. It’s fascinating to see how much the coastline has changed due to landfill and erosion.

- Check the Logbooks: Read the primary source accounts. Robert Juet’s journal of the 1609 voyage is public domain. It’s gritty, full of drama, and gives you a better sense of the map than any drawing can.

The map of henry hudson voyages is a record of a man who was consistently wrong about geography but accidentally right about where the future of global trade would lie. He never saw the Orient, but he put the markers on the map that led to the creation of the modern Western world.