August 9, 1969. It was hot. Los Angeles was thick with that stagnant, high-summer smog that makes everything feel just a little bit heavy. When Winifred Chapman, the housekeeper for Roman Polanski and Sharon Tate, walked up the driveway of 10050 Cielo Drive that morning, she expected a normal shift. She found a nightmare instead. The Manson murders crime scene wasn't just a site of extreme violence; it was a chaotic, ritualistic mess that fundamentally broke the psyche of the American public. You've seen the photos—the grainy black-and-whites of the word "PIG" scrawled in blood on the front door—but the reality of the scene was even more disjointed and confusing than the headlines suggested.

Honestly, the police blew it at first.

The initial response from the LAPD was messy. They didn't realize they were looking at a cult hit. They thought it was a drug deal gone sideways. Officers walked through the blood. They touched things. They didn't even realize there were more bodies down by the gate for a while. It’s hard to wrap your head around how a scene that famous could be handled so poorly in those first few hours, but you have to remember: people didn't do this back then. Not in Beverly Hills. Not to movie stars.

The Chaos at 10050 Cielo Drive

When you look at the layout of the Manson murders crime scene, the first thing that hits you is the sheer distance between the victims. It wasn't a concentrated struggle. It was a hunt. Steven Parent, just 18 years old, was the first to die, slumped in his car near the gate. He was just in the wrong place at the wrong time, trying to sell a radio to the property's caretaker.

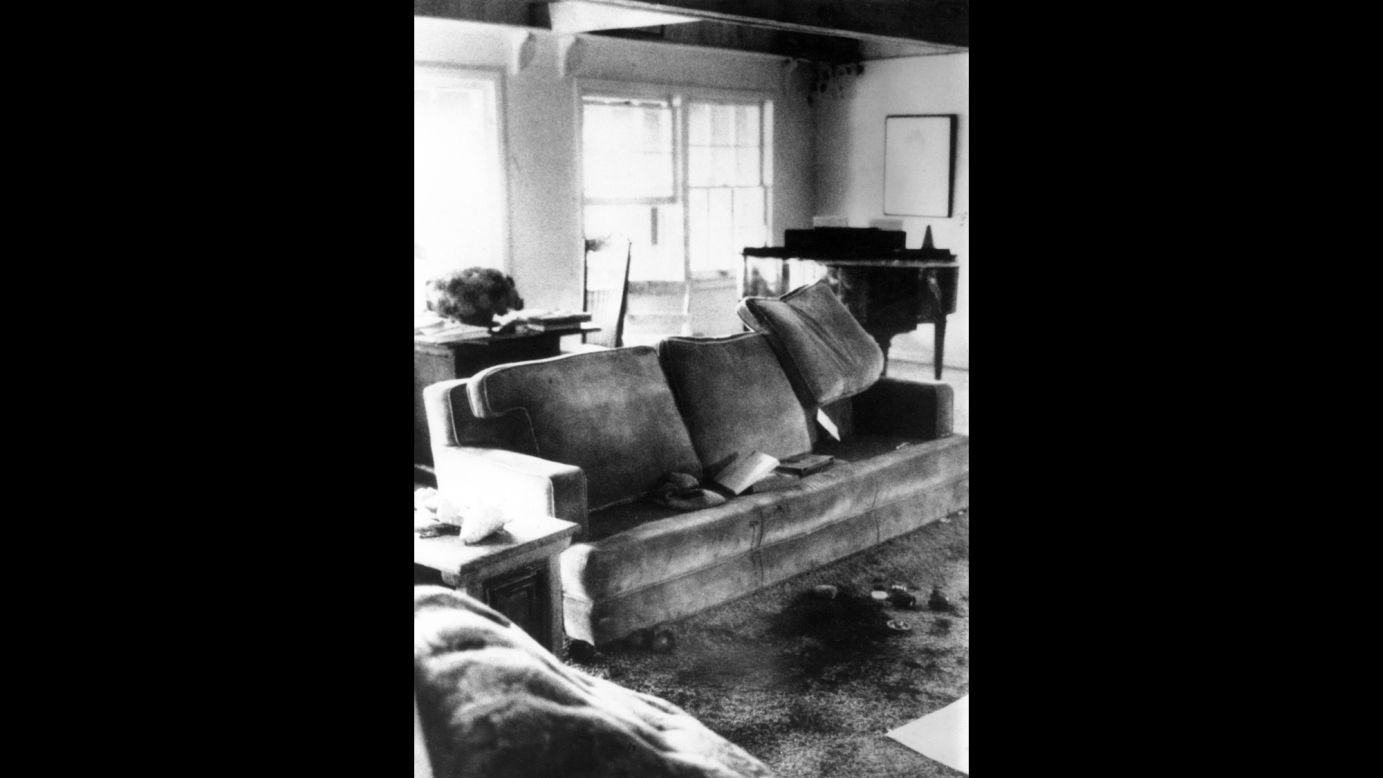

Inside the house, the scene was grisly. Sharon Tate and Jay Sebring were found in the living room, connected by a long piece of white nylon rope looped around their necks. The rope had been flung over a ceiling beam. It’s a detail that sounds like something out of a horror movie, but it was real life. The sheer amount of blood on the floor made it difficult for investigators to even walk without slipping.

✨ Don't miss: Ukraine War Map May 2025: Why the Frontlines Aren't Moving Like You Think

Then there were Abigail Folger and Wojciech Frykowski. They didn't die inside. They made a break for it. Their bodies were found on the lawn, dozens of yards away from the house. Folger’s white nightgown was so soaked in red that it looked like a different garment entirely. The struggle was frantic. It was long. It wasn't the clean, cinematic "assassination" people sometimes imagine. It was a desperate, terrifying scramble for life in the dark.

The LaBianca Connection and the Second Scene

A lot of people forget that the Manson murders crime scene actually spans two nights and two different locations. The night after the Cielo Drive massacre, the "Family" hit the home of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca in Los Feliz. This scene was different. It was more controlled, which in many ways makes it scarier.

Leno LaBianca was found with a carving fork protruding from his stomach. The word "WAR" had been carved into his flesh. This wasn't just murder; it was a message. While the Tate scene felt like a panicked explosion of violence, the LaBianca scene felt like a cold, calculated performance. The killers even stayed for a while. They ate food from the victims' fridge. They played with the dogs.

Why the Evidence Was Such a Mess

The forensic science of 1969 wasn't what it is today. No DNA profiling. No digital mapping of blood spatter. The lead investigator, Danny Galindo, had to rely on basic fingerprinting and physical evidence that was being contaminated by the minute.

🔗 Read more: Percentage of Women That Voted for Trump: What Really Happened

One of the biggest mistakes? The glasses. A pair of horn-rimmed glasses was found at the Tate house. They didn't belong to any of the victims. For a long time, the LAPD thought they belonged to the killer. It turns out they were likely just dropped during the struggle, but the obsession with these small physical details often distracted from the bigger picture—the fact that a group of nomadic hippies living on a junk-filled movie ranch was responsible.

- Contamination: Reporters were practically breathing down the necks of the officers.

- The "PIG" Door: The blood used to write on the door began to dry and flake before it could be properly analyzed for consistency.

- The Gun: The .22-caliber Hi-Standard Buntline Special used in the killings was actually found by a kid, Steven Weiss, in his backyard miles away. He turned it in, but the police didn't connect it to the Manson case for months.

Breaking Down the "Helter Skelter" Narrative

Vincent Bugliosi, the prosecutor who wrote Helter Skelter, framed the entire Manson murders crime scene around a race war. He argued that Charles Manson wanted to incite a conflict between Black and white Americans by framing Black activists for the murders.

But if you talk to some of the surviving Family members or researchers like Tom O'Neill (author of Chaos), the story gets murkier. O'Neill spent twenty years digging into the case and found massive holes in the official story. Was Manson actually trying to get a friend out of jail? Was there a connection to the drug world that the LAPD wanted to keep quiet?

The "race war" motive is what stuck because it’s terrifying and easy to understand. But the scene itself suggests something more personal and perhaps more disorganized. Manson had been to the Cielo Drive house before. He knew the previous tenant, Terry Melcher, a record producer who had rejected Manson’s music. The scene wasn't just a political statement; it was a grudge.

💡 You might also like: What Category Was Harvey? The Surprising Truth Behind the Number

The Visual Language of the Crime

Every surface of the house seemed to tell a story of someone trying to escape. There were bloody handprints on the porch. There were clumps of hair. The sheer number of stab wounds—102 across the five victims at the Tate house—speaks to a level of overkill that goes beyond simple homicide. It’s what profilers call "over-signifying." The killers weren't just ending lives; they were trying to destroy the very idea of the people they were killing.

The contrast was jarring. You had this beautiful, secluded estate—the epitome of the "Summer of Love" era’s success—covered in the visceral reality of a group that hated everything that success stood for.

What We Can Learn From the Scene Today

Studying the Manson murders crime scene isn't just about the macabre fascination with a cult. It's about understanding the shift in American culture. Before these murders, people in L.A. left their doors unlocked. They trusted their neighbors. After August 1969, the locks went on, the guard dogs were bought, and the "peace and love" era officially died.

If you're researching this for a project or just because you're a true crime fan, focus on the physical discrepancies. Look at the police reports (many are now public domain) and compare them to the trial testimony. You’ll find that the "perfect" narrative of the Manson Family often clashes with the messy, disorganized reality of what was left behind on the floor of that living room.

Actionable Steps for Deeper Research

If you want to understand the forensic side of this better, here is what you should actually do:

- Read the Autopsy Reports: They are widely available online. Look at the directionality of the wounds. It reveals a lot about the height and position of the attackers compared to the victims.

- Look at the Spiering Photos: Not for the gore, but for the placement of the furniture. The tipped-over chairs and moved rugs show the "drift" of the fight, which contradicts the idea that the victims were totally compliant.

- Cross-Reference with "Chaos" by Tom O'Neill: This book is essential. It challenges the Bugliosi narrative using the FBI’s own documents.

- Check the Timeline: Use the LAPD logbooks to see exactly when the scene was secured. You'll notice a massive gap between the discovery of the bodies and the actual start of a coordinated investigation.

The Manson murders crime scene remains one of the most studied locations in criminal history, not because we don't know who did it, but because the "why" still feels so slippery. Even with the killers behind bars (or dead), the site itself—now demolished and replaced by a new mansion with a different address—continues to haunt the hills of California. It serves as a permanent reminder of how quickly a dream can turn into a waking nightmare.