History is messy. Usually, when we talk about the French Resistance, we picture berets and baguettes, maybe a suave spy in a trench coat. But the reality of the Army of Crime—or L'Affiche Rouge (The Red Poster)—is way more complicated, gritty, and, frankly, heartbreaking. It wasn't just "Frenchmen" fighting Germans. It was a ragtag group of immigrants, Jews, communists, and poets who did the dirty work while much of the local population was just trying to keep their heads down.

They were outsiders.

The term "Army of Crime" actually came from Nazi propaganda. In February 1944, the Vichy government and the German occupiers plastered 15,000 bright red posters across Paris. These posters featured the faces of ten Resistance members, mostly foreign-born, looking disheveled and "criminal." The goal was to scare the French public. The Nazis wanted to say: "Look, these aren't patriots; these are foreign terrorists and bandits." It backfired. People started leaving flowers under the posters. They saw these "criminals" as the only ones actually doing something.

Who were the people in the Army of Crime?

Missak Manouchian is the name you’ll hear most. He was an Armenian poet. Think about that for a second. A guy who spent his life obsessed with stanzas and metaphors ended up leading a lethal urban guerrilla cell in the heart of occupied Paris. He wasn't some career soldier. He was a survivor of the Armenian Genocide who moved to France because he loved the culture. He lived in a tiny apartment, worked in a factory, and wrote verses.

But by 1943, he was the military chief of the FTP-MOI (Francs-tireurs et partisans – main-d'œuvre immigrée). This was a wing of the resistance specifically for immigrants.

The group was a melting pot. You had Marcel Rayman, a Polish Jew who was barely twenty and became one of their most effective assassins. You had Celestino Alfonso, a Spaniard who had already fought in the Spanish Civil War. You had Olga Bancic, a Romanian woman who handled the logistics and transport of explosives. They weren't just "fighting for France" in a nationalist sense. They were fighting against fascism because they had nowhere else to go. For many of them, France was the last stop.

Honestly, their life was miserable. They lived in constant fear. They couldn't stay in the same place for more than a few nights. They had no money. They were often starving. Yet, between August and November 1943, the Manouchian Group carried out nearly 100 armed actions. They blew up trains. They threw grenades into German hotels. They shot high-ranking officers in broad daylight.

The assassination of Julius Ritter

If you want to understand why the Nazis were so obsessed with the Army of Crime, look at September 28, 1943. That morning, Julius Ritter was getting into his car. Ritter wasn't just any officer; he was the man in charge of the STO (Service du travail obligatoire), the program that forced French workers into slave labor in Germany.

He was a marked man.

💡 You might also like: Passive Resistance Explained: Why It Is Way More Than Just Standing Still

Four members of the Manouchian group waited for him. Marcel Rayman was there. Celestino Alfonso fired the first shots. It was a clinical, brutal execution. This wasn't a "gentleman’s war." It was urban warfare at its most raw. The death of Ritter sent shockwaves through the German command. It proved that even the highest-ranking officials weren't safe in the streets of Paris. It also sealed the fate of the group. The Gestapo put their best people on the case, eventually deploying the Brigades Spéciales (BS2), a specialized French police unit that hunted down "terrorists."

How they were caught: The myth of the "Great Betrayal"

People love a good betrayal story. For decades, there were rumors that the French Communist Party (PCF) intentionally "gave up" the Manouchian group to the police. The theory was that the party wanted to get rid of the "foreigners" to make the Resistance look more "purely French" for the post-war government.

It’s a spicy theory. But the reality is probably more mundane and more tragic.

The BS2 was incredibly good at their jobs. They didn't need a tip-off. They used "shadowing" techniques that would make modern detectives blush. They followed one member to a meeting, then followed the people from that meeting to their homes. They mapped out the entire network over months. By the time they moved in for the arrests in November 1943, they knew almost everyone.

They were tortured. For weeks.

None of them broke quickly. Olga Bancic was beaten so badly she was unrecognizable. Manouchian was subjected to the "bathtub" and other horrors. Eventually, the Germans had what they needed for a show trial. They wanted to prove that the Resistance was a "foreign plot."

The Trial and the Red Poster

The trial took place in February 1944 at the Hôtel Continental. It was a sham, obviously. Twenty-three people were sentenced to death. On February 21, 1944, twenty-two of the men were taken to Mont Valérien and executed by firing squad.

Olga Bancic was the exception. Under French law, you couldn't execute a woman by firing squad. So, the Nazis took her to Stuttgart, Germany, and beheaded her with an axe on her 32nd birthday.

📖 Related: What Really Happened With the Women's Orchestra of Auschwitz

The Army of Crime poster was released right around this time. The Nazis thought it would make the public hate them. The poster showed photos of the "terrorists" alongside pictures of derailed trains and piles of weapons. The text asked: "Liberators? Liberation by the army of crime!"

They totally misread the room. Parisians saw these faces—some of them young, some of them looking like their neighbors—and realized that while the official French army had surrendered in weeks, these "foreigners" were still fighting. It became a symbol of defiance.

The Letter to Mélinée

If you want to cry, read Manouchian’s final letter to his wife, Mélinée. He wrote it just hours before his execution. He didn't sound like a "criminal." He sounded like a man who was deeply at peace with his choices but devastated to leave his love.

He wrote: "I die with my conscience at rest... I have no hatred for the German people."

That’s a heavy line. After everything they did to him, he still distinguished between the Nazi regime and the people. He told Mélinée to get married again and have a child in his honor. She never did. She spent the rest of her life making sure he was remembered.

Why we’re still talking about this in 2026

For a long time, the Army of Crime was a footnote. After the war, Charles de Gaulle wanted to build a narrative of "a nation that liberated itself." He needed heroes like Jean Moulin—French, military, "respectable." The immigrant communists didn't fit the vibe of the 1950s.

But things shifted. In 2024, Missak and Mélinée Manouchian were finally inducted into the Panthéon. That’s the highest honor in France. It’s the place where Victor Hugo and Marie Curie are buried. It took eighty years, but the "Army of Crime" finally became the "Army of France."

It’s a reminder that identity is fluid. These people weren't born French, but they died for the idea of what France should be: Liberté, égalité, fraternité. They took those words more seriously than many people who were born into them.

👉 See also: How Much Did Trump Add to the National Debt Explained (Simply)

What most people get wrong

There’s a misconception that these guys were just "hired guns" for the Soviet Union. While they were communists, their motivations were deeply personal. Many were Jews who had seen their families deported. Many were refugees from fascist regimes in Italy or Spain. They weren't just following orders from Moscow; they were fighting for their own survival.

Also, they weren't "amateurs." They were incredibly organized. They had separate cells for intelligence, logistics, and execution. They used complex codes. If one person was caught, they had protocols to cut off that branch of the network immediately. The only reason the whole thing collapsed was the sheer scale of the French police surveillance.

Real-world takeaways and how to learn more

If you’re interested in this era, don't just stick to the history books. History is about people, not just dates.

- Visit Mont Valérien: If you’re ever in Paris, go to the memorial. It’s a sobering place. You can see the clearing where they were shot.

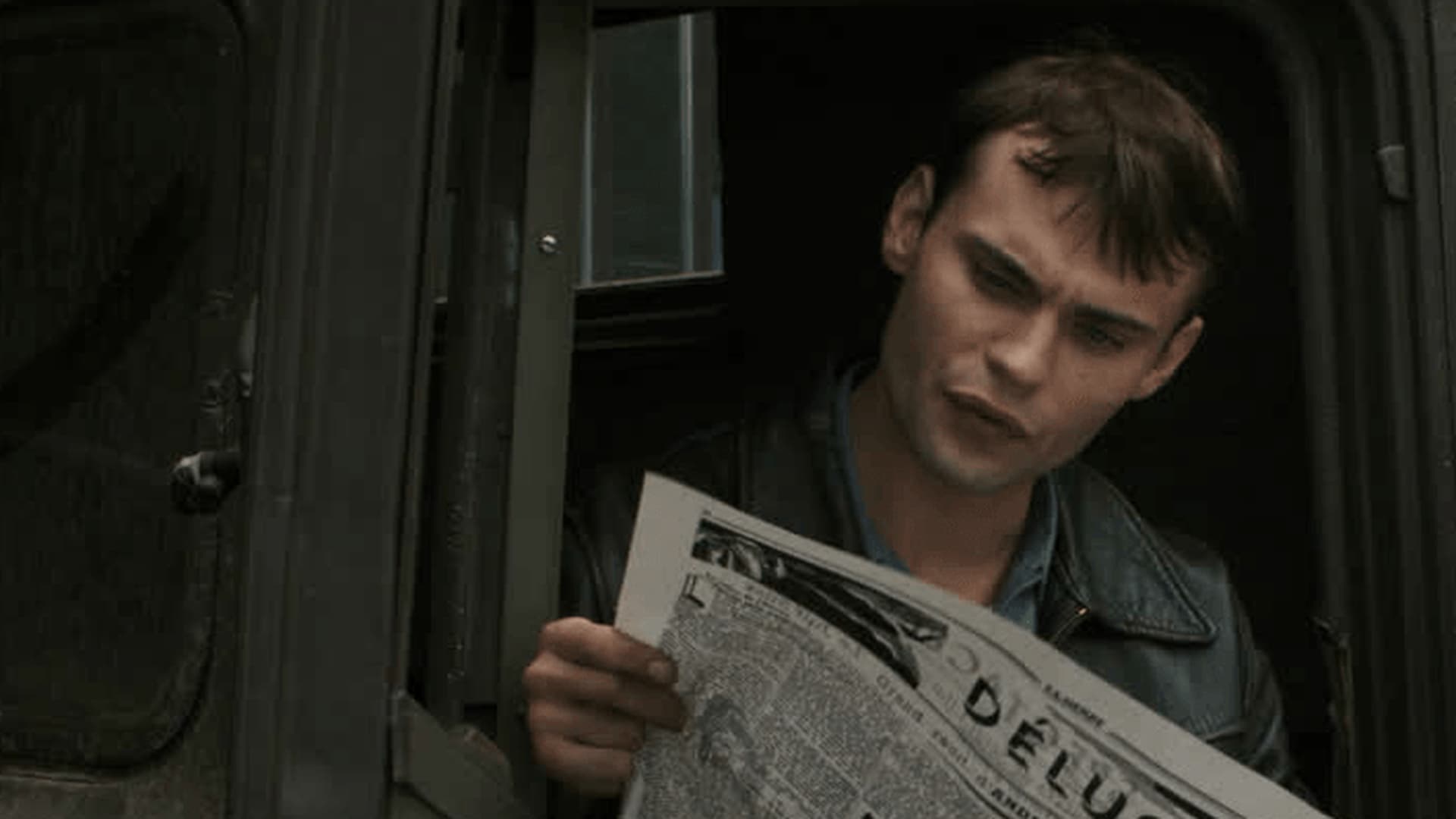

- Watch 'The Army of Crime' (L'Armée du crime): Robert Guédiguian directed a film in 2009 that captures the grit and the tension of the Manouchian group. It’s not a shiny Hollywood movie; it’s dirty and claustrophobic.

- Read the poetry: Look up Missak Manouchian’s poems. It gives you a glimpse into the soul of a man who chose violence only because he felt he had no other choice to protect the beauty he wrote about.

- Search the archives: The French national archives have digitized many of the original police reports from the BS2. Seeing the "Army of Crime" through the eyes of the people hunting them is chilling.

The story of the Army of Crime is a lesson in nuance. It shows that heroes are often messy, complicated, and labeled as villains by the powers that be. It reminds us that "foreigner" is a label that says more about the person using it than the person receiving it.

The next time you see a statue or a plaque for the Resistance, look for the names that don't sound "traditionally" French. Those are the people who had the most to lose and the least to gain, yet they stayed in the fight anyway.

To really understand the Army of Crime, you have to look past the red poster and see the people behind it: the poets, the seamstresses, and the young men who decided that a short life of resistance was better than a long life of collaboration. That’s the real legacy. It’s not about the crimes; it’s about the courage to be called a criminal for doing what’s right.

Move beyond the surface-level history. Look into the specific stories of members like Thomas Elek or Wolf Wajsbrot. Their individual paths to Paris tell the story of a broken Europe trying to find its soul again. Study the "Red Poster" itself; analyze how the graphic design was used as a weapon of psychological warfare. Finally, reflect on how long it takes for a society to acknowledge those who fought for it from the margins. Recognition isn't always immediate, but as the Panthéon induction shows, the truth eventually finds its way home.