It was February 6, 1958. A Thursday. Most people think the Manchester United air disaster was just a freak accident caused by bad luck, but when you actually look at the mechanics of what happened at Munich-Riem Airport, it’s a lot more frustrating than that. It was a series of small, avoidable pressures that snowballed—literally—into a tragedy that nearly erased one of the greatest football teams ever assembled.

The "Busby Babes" weren't just a good squad. They were a revolution. Matt Busby had built a team with an average age of about 22, and they were tearing through the European Cup. They had just secured a 3-3 draw against Red Star Belgrade, clinching their spot in the semi-finals. Everyone was buzzing. But the flight home turned into a nightmare that changed football forever.

The Myth of Engine Failure

You often hear people say the engines failed. That’s not quite right. The plane, a British European Airways Airspeed Ambassador named the Lord Burghley, was actually fine mechanically. The problem was the slush on the runway.

Captain James Thain and Co-Pilot Kenneth Rayment had already tried to take off twice. Both times, they abandoned the attempt because of "boost surging"—basically, the engines weren't behaving perfectly in the freezing conditions. Most pilots might have called it a day. But there was pressure. Pressure to keep the schedule. Pressure to get the team home.

On the third attempt, they hit a patch of slush at the end of the runway.

The plane reached "V1" speed—the point of no return. But then, something weird happened. Instead of accelerating to liftoff speed, the aircraft actually slowed down. The slush acted like a giant brake, dragging the wheels back. The plane plummeted from 117 knots to 105 knots in seconds. They ran out of tarmac, smashed through a fence, and the left wing clipped a house.

It was chaos.

✨ Don't miss: What Time Did the Cubs Game End Today? The Truth About the Off-Season

The Human Toll and the Immediate Aftermath

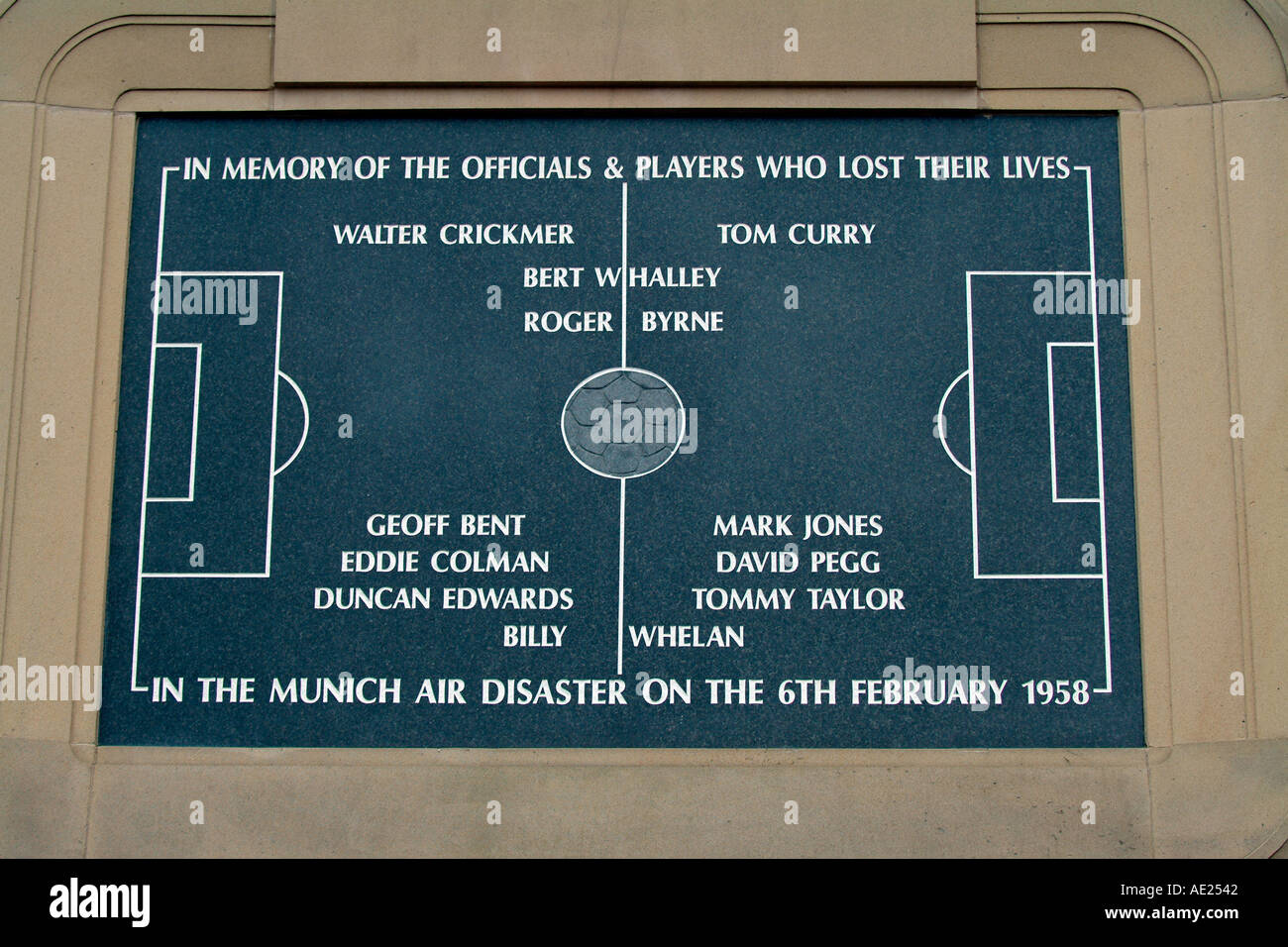

Twenty-three people died. It’s a number that’s easy to read but hard to process. Eight of those were players: Geoff Bent, Roger Byrne, Eddie Colman, Duncan Edwards, Mark Jones, David Pegg, Tommy Taylor, and Billy Whelan.

Duncan Edwards survived the initial crash. He was the crown jewel of English football. People who saw him play, like Bobby Charlton, still say he was the only player who ever made them feel inferior. He fought for 15 days in a German hospital before his kidneys gave out. He was only 21.

The scene at the crash site was horrific. Harry Gregg, the goalkeeper, became an instant hero, though he’d hate you for calling him that. He crawled back into the wreckage to pull out teammates and a pregnant woman and her daughter. He thought the plane was going to blow at any second. He just did it.

- The Journalists: Eight sportswriters died too. They were part of the inner circle back then, traveling on the same planes as the players, drinking in the same pubs.

- The Staff: Tom Curry and Bert Whalley, the coaching backbone, were lost.

- The Survivors: Matt Busby was read his last rites twice. He survived, but the guilt he carried was immense. He’d pushed for the European Cup competition against the wishes of the Football League. He felt responsible for putting his boys on that plane.

Why the Germans Blamed the Pilot (And Why They Were Wrong)

For years, the German authorities blamed Captain James Thain. They claimed he hadn't de-iced the wings. They produced a photo that supposedly showed ice buildup.

Thain fought for ten years to clear his name. It was a lonely, expensive battle. Eventually, it was proven that the "ice" in the photo was actually just melting snow and reflections. The real culprit was the runway maintenance—or lack thereof. The airport hadn't cleared the slush properly, and at high speeds, that slush creates a drag factor that no engine can overcome.

It wasn't until 1969 that Thain was officially cleared of responsibility by the British government. He never flew again. He spent his later years running a poultry farm, a quiet end for a man who had been the scapegoat for a national tragedy.

🔗 Read more: Jake Ehlinger Sign: The Real Story Behind the College GameDay Controversy

The Resurrection: 1968 and the Long Road Back

How do you rebuild a team when half of them are gone?

Jimmy Murphy. That’s the name you need to know. He was Busby’s assistant and wasn't on the plane because he was managing Wales in a World Cup qualifier. While Busby was recovering in an oxygen tent, Murphy kept the club alive. He signed "fill-in" players, scouted youngsters, and somehow dragged a broken squad to the FA Cup final just months later.

They lost that final, but the fact they were there at all was a miracle.

It took ten years to come full circle. In 1968, Manchester United finally won the European Cup at Wembley. Bobby Charlton, a survivor who still carried the physical and mental scars of Munich, scored twice. After the final whistle, he didn't celebrate wildly. He and Busby shared a quiet, tearful embrace. They had finally finished the job the 1958 team started.

Impact on Modern Aviation Safety

One thing people don't realize is how much the Manchester United air disaster changed flying for the rest of us.

Before Munich, nobody really understood "slush drag." We knew ice on wings was bad, but the idea that a couple of inches of watery snow on the ground could stop a plane from taking off wasn't fully respected. Because of the investigation into this crash, airports worldwide changed their protocols for runway clearance.

💡 You might also like: What Really Happened With Nick Chubb: The Injury, The Recovery, and The Houston Twist

Modern pilot training also changed. The concept of "Decision Speed" (V1) became much more strictly defined. Today, if a pilot feels the slightest drag in those conditions, the takeoff is aborted long before the point of no return.

What Most People Get Wrong

People often treat the disaster as a tragic piece of "sporting lore," but it was a systemic failure. The Football League, led by Alan Hardaker, was incredibly hostile toward the European Cup. They made United's schedule nearly impossible, refusing to move domestic fixtures.

This meant the team was constantly rushing. If the League had been more flexible, United wouldn't have been in such a hurry to fly back in a blizzard. They might have stayed an extra night in Belgrade or Munich until the weather cleared.

Also, the "Babes" weren't just a bunch of kids who got lucky. Tactically, they were years ahead of their time. They played a fluid, attacking style that most English teams didn't adopt until the 1970s. We didn't just lose players; we lost a decade of tactical evolution in the English game.

Moving Forward: How to Honor the History

If you really want to understand the impact of the Munich air disaster, you have to look beyond the statues and the "Munich Clock" at Old Trafford. You have to look at the club's DNA. The reason Manchester United has such a massive global following isn't just because of the trophies in the 90s; it’s because of the romantic, tragic story of a team that died and a club that refused to stay buried.

Practical steps for fans and historians:

- Visit the Munich Tunnel: If you're ever in Manchester, go to the south side of Old Trafford. It’s a permanent memorial that’s free to visit. It’s quiet, somber, and gives you a real sense of the scale of the loss.

- Read "The Day a Team Died": Frank Taylor was the only journalist to survive the crash, and his first-hand account is probably the most raw and honest version of the story you'll find.

- Watch the 1958 FA Cup Final footage: Look at the faces of the fans. You’ll see a city in mourning, but also a city finding its feet again.

- Support the Survivors' Legacy: The Manchester United Foundation does a lot of work with youth, which is the best way to honor a team that was defined by its youth.

The disaster didn't just break hearts; it forged a specific identity of resilience. Every time a young player debuts for United today, there’s a direct line back to the philosophy Matt Busby was trying to build before the snow in Munich changed everything.