Gertrude Stein didn’t care if you finished her book. Honestly, she probably didn't even care if you liked it. Most people who pick up The Making of Americans don't actually make it through all nine hundred-plus pages, and that’s perfectly fine by the standards of the Lost Generation. It is a beast of a book. It’s repetitive, it’s circular, and it tries to map out every single type of human being that has ever existed or will exist.

You’ve probably heard of Stein because of her Paris salon or her friendship with Picasso, but this specific novel is her "magnum opus" that almost nobody actually reads. It’s a generational saga, but not like the ones you find on the bestseller list today. There’s no juicy plot about inheritance or secret affairs. Instead, it’s a slow-motion study of how families move, how they change, and how they basically become "American."

What actually happens in The Making of Americans?

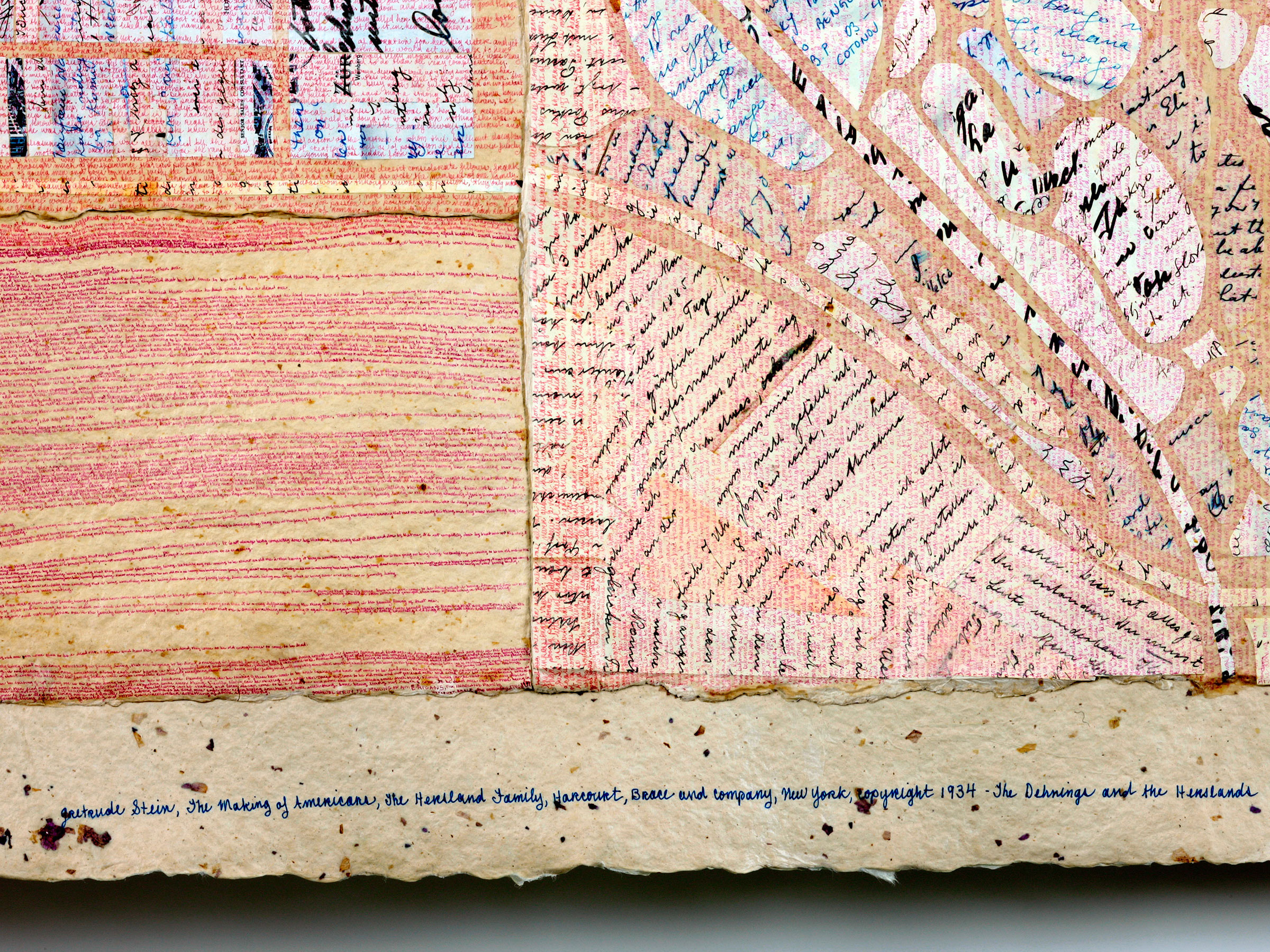

If you're looking for a traditional narrative, you’re going to be disappointed. The book follows the Dehning and Hersland families. They are middle-class, they have German roots, and they are trying to establish themselves in the United States. But Stein isn't interested in the "what." She’s obsessed with the "how."

She uses a technique she called the "prolonged present."

Imagine a person telling you a story, but they keep circling back to the same phrase, adding just one new word each time. That’s the Stein experience. She wanted to capture the rhythm of consciousness. She believed that everyone has a "bottom nature"—a fundamental way of being that repeats throughout their life. By repeating words and phrases over and over, she felt she was peeling back the skin of the characters to show that inner core.

It’s exhausting. It’s also brilliant if you’re into linguistics.

👉 See also: Campbell Hall Virginia Tech Explained (Simply)

The struggle to get it published

Stein started writing The Making of Americans around 1903 and didn't finish until 1911. For over a decade, the manuscript just sat there. Nobody wanted to touch it. It was too long, too weird, and far too expensive to print during a time when paper was a major commodity.

It wasn't until 1925 that Robert McAlmon’s Contact Press finally put it out. Even then, it wasn't a hit. Hemingway actually helped edit the proofs, which is hilarious when you think about how different his "short and punchy" style is from Stein’s "never-ending" style. Hemingway famously complained about the sheer volume of the text, but he also admitted that he learned a lot about rhythm from her.

Why the "Bottom Nature" concept matters

Stein’s big idea was that you could categorize every person on earth. She spent years watching people in her salon—artists, writers, socialites—and trying to fit them into these "types."

In the novel, she explores how the first generation of an immigrant family has one kind of energy, while the second and third generations lose that "muddied" connection to the old world and become something else. This is the "making" part of the title. It’s the process of losing an old identity to gain a new, perhaps flatter, one.

- She looked at "independent-dependent" types.

- She analyzed "resisting" natures versus "attacking" natures.

- She focused on the way people eat, walk, and repeat their mistakes.

It’s less of a novel and more of a psychological map. If you read it closely, you start to notice your own repetitions. You realize that you probably say the same three things to your friends every single week. Stein caught onto that human glitch before modern psychology really had a name for it.

✨ Don't miss: Burnsville Minnesota United States: Why This South Metro Hub Isn't Just Another Suburb

The connection to Cubism

You can't talk about The Making of Americans without talking about painting. Stein was living in the middle of a revolution. She was buying works by Matisse and Picasso when they were still considered "trash" by the mainstream art world.

She wanted to do with words what Picasso was doing with a canvas.

When you look at a Cubist painting, you see the same object from five different angles at once. Stein does that with sentences. She describes a character's "being" from multiple linguistic angles until the reader is dizzy. It’s fragmented. It’s messy. It’s also deeply influential. Without this experiment, we wouldn't have the stream-of-consciousness style that made James Joyce or Virginia Woolf famous.

Why people get it wrong

A lot of critics categorize this book as "unreadable" and leave it at that. That’s a lazy take. It's actually very readable if you stop trying to "get to the end." If you treat it like a piece of ambient music—something that washes over you—it starts to make sense.

The misconception is that Stein was being difficult on purpose just to be an elitist. In reality, she was trying to be more "real" than other writers. She thought traditional plots were fake. Life doesn't have a plot; life has a rhythm. We wake up, we do the same things, we talk to the same people, and we slowly get older. That’s what she put on the page.

🔗 Read more: Bridal Hairstyles Long Hair: What Most People Get Wrong About Your Wedding Day Look

The legacy of a 900-page experiment

Even if you never finish the book, you are living in a world shaped by it. Every time you read a book that focuses on "vibes" or "interiority" over plot, you're seeing a ghost of Stein.

The Making of Americans served as a bridge. It took the 19th-century family chronicle—think George Eliot or Thomas Mann—and smashed it into the 20th-century obsession with the individual mind. It’s the missing link in American literature.

It also tells a very specific story about the American immigrant experience that isn't wrapped in a bow. It acknowledges the boredom, the stagnation, and the slow erasure of heritage. It’s not a "pull yourself up by your bootstraps" story. It’s a "watch how these people slowly turn into something unrecognizable to their ancestors" story.

How to actually approach reading it

If you’re brave enough to try it, don't start at page one and expect to be finished by Sunday.

- Read it aloud. Stein’s prose is meant to be heard. The repetitions make more sense when they have a physical rhythm.

- Focus on the "Hersland" sections. The middle of the book contains some of the most profound observations on how parents and children fail to understand each other.

- Don't worry about the names. The characters often blur together. That’s intentional. They are types, not just individuals.

- Check out the abridged versions. Leon Katz and others have produced shorter versions that cut the 900 pages down to a more manageable 400. It’s not the "pure" experience, but it’s a lot better than never reading it at all.

Stein once said, "It is very difficult to leave anything out of a book when you are putting everything in." She definitely put everything into this one. It’s a monument to the idea that every life, no matter how repetitive or "boring," is worth a thousand pages of documentation.

Actionable Insights for the Curious Reader

- Start with the "Selected Writings": Before diving into the full novel, read Stein's "Melanctha" from Three Lives. It’s a shorter example of her repetitive style and acts as a "training manual" for her longer works.

- Listen to recordings: There are rare recordings of Stein reading her own work. Hearing her voice helps you understand where the emphasis should go in her long, comma-less sentences.

- Look at the portraits: Find a digital gallery of Picasso's portrait of Gertrude Stein. Study it while you read. The "heavy" and "mask-like" quality of the painting perfectly mirrors the prose in The Making of Americans.

- Track your own repetitions: For one day, try to notice the phrases you use most often. You'll likely find that you have a "bottom nature" of your own that Stein would have found fascinating.

The book isn't just a novel; it's a test of patience and a different way of seeing the world. Whether you find it brilliant or infuriating, it remains one of the most honest attempts to capture the sheer scale of what it means to be a human being in a new country.