Your lower back is a mess of tension. Honestly, most of us treat the lumbar region muscles like a structural afterthought until we’re bent over a sink, unable to brush our teeth because of a sudden, searing spasm. It’s not just "back pain." It’s a complex failure of a pulley system that literally holds your torso upright against the relentless pull of gravity.

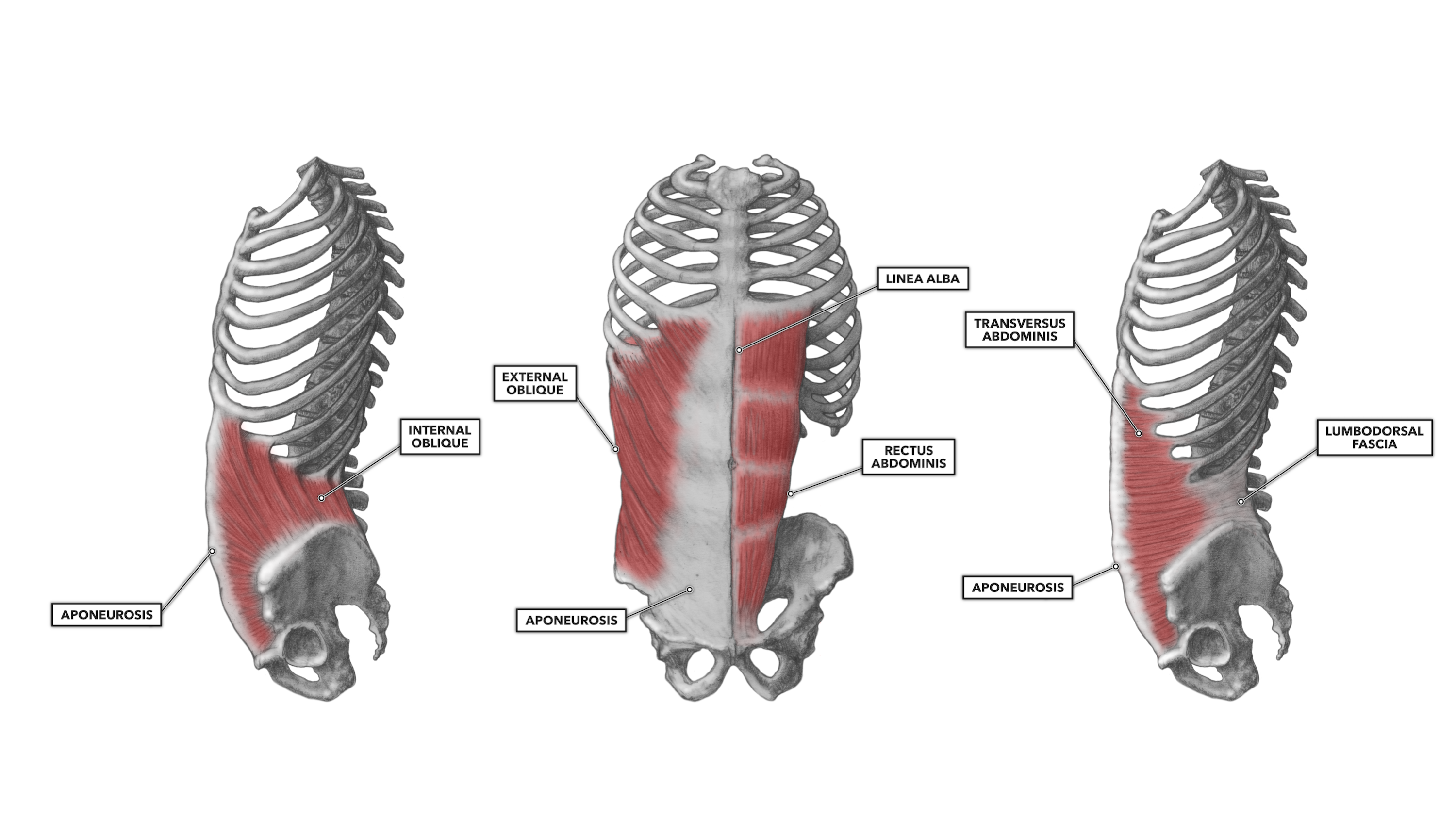

We talk about "the core" like it's just a six-pack. Ridiculous.

The real power—the stuff that keeps you out of a surgeon’s office—lives in the deep layers of the low back. If you want to understand why your back feels like a rusty hinge, you have to look at the anatomy that Google usually simplifies into tiny, useless diagrams.

The Deep Layer: Multifidus and the Stability Myth

Most people have never heard of the multifidus. It’s this tiny, feather-like muscle that runs along the spine. It doesn't look like much. But here’s the thing: research from experts like Dr. Stuart McGill, a titan in spine biomechanics, shows that the multifidus is the first muscle to atrophy when you have back pain. It’s like a stabilizer bar on a car. If it goes soft, the whole frame starts to rattle.

The multifidus provides segmental stability. This means it controls the tiny movements between individual vertebrae. When you sit in a bucket seat for six hours, these muscles basically go to sleep. They stop firing. Then, you stand up, reach for a heavy bag of groceries, and—snap—your brain panics because the stabilizers weren't "on." This is where the cycle of chronic pain usually starts. It isn't a "weak" back; it's a "disconnected" back.

The Psoas Connection

Then there’s the psoas. It’s the only muscle that connects your spine to your legs. It’s deep. It’s temperamental. Because it attaches directly to the lumbar vertebrae, a tight psoas (from all that sitting) literally yanks on your spine from the inside out. It creates an anterior pelvic tilt. You've seen it—that "duck butt" posture where the lower back is excessively arched. That arch puts massive pressure on the facet joints.

💡 You might also like: Can I overdose on vitamin d? The reality of supplement toxicity

Why Your Lumbar Region Muscles Are Always Angry

We live in a world designed to kill the posterior chain. Think about it. We drive, we sit at desks, we look at phones. Everything is "front-loaded." This leaves the muscles in the lumbar region overstretched and underactive.

Take the Erector Spinae. This is a group of three muscles: the iliocostalis, longissimus, and spinalis. They are the big vertical cables you see on bodybuilders. Their job is to keep you standing. But when they have to do the work of the deeper stabilizers, they get overworked. They become "hypertonic." That’s the tightness you feel after a long day of standing. It’s not that they are strong; it’s that they are exhausted from doing someone else's job.

- Quadratus Lumborum (QL): This is the "hiker" muscle. It connects your pelvis to your lowest rib. If one side is tighter than the other, your hips will be unlevel. Ever feel like one leg is shorter than the other? It’s probably your QL acting like a stubborn rubber band.

- Transverse Abdominis: Technically an abdominal muscle, but it’s the body’s natural weight belt. It wraps around to the back. If this isn't bracing, your lumbar muscles take the hit.

The Misconception of "Stretching" It Out

You feel tight, so you stretch. Right?

Maybe not.

If your lumbar muscles are tight because they are trying to protect an unstable spine, stretching them is the worst thing you can do. You’re essentially pulling on a knot that’s holding a bridge together. Dr. McGill often argues against the traditional "knees-to-chest" stretch for people with certain types of disc issues because it increases spinal flexion and can actually push disc material further out.

📖 Related: What Does DM Mean in a Cough Syrup: The Truth About Dextromethorphan

Instead of stretching, many people actually need stiffness. Not the "I can't move" kind of stiffness, but the "armored" kind. You want your spine to be a rigid mast supported by those muscular cables.

The Role of the Latissimus Dorsi

Wait, the lats? The "wing" muscles under your arms?

Yes.

The lats are massive. They attach to the thoracolumbar fascia—a thick sheet of connective tissue in your lower back. When you engage your lats (think of "tucking your shoulder blades into your back pockets"), you actually tighten that fascia. This creates a natural corset effect. It’s why powerlifters "set" their lats before a heavy deadlift. It turns the lumbar region muscles into a cohesive, armored unit.

Real-World Mechanics: The "Spasm" Explained

A back spasm is basically your brain’s emergency brake. It’s a "protective guarding" mechanism. When the nervous system senses that the vertebrae are at risk of slipping or the discs are under too much shear force, it sends a massive electrical signal to the lumbar region muscles to lock everything down.

👉 See also: Creatine Explained: What Most People Get Wrong About the World's Most Popular Supplement

It hurts like hell.

But the muscle isn't the problem; it's the messenger. The real issue is usually a lack of coordination between the diaphragm (breathing) and the pelvic floor. If you can't breathe into your belly while keeping your core braced, your lower back is doing 100% of the stabilization work. That’s a recipe for a blowout.

Actionable Steps to Wake Up Your Back

Stop doing a million crunches. They just reinforce the flexion that’s already hurting you. If you want to actually support your lumbar anatomy, you need to change how you move.

- The Bird-Dog: This isn't just a yoga move. It’s a neurological recalibration. By extending the opposite arm and leg, you force the multifidus to fire. Keep your back flat—imagine a glass of water sitting on your tailbone. Don't let it spill.

- The Side Plank: Most back pain is actually a lack of lateral stability. The QL loves the side plank. It builds endurance without crushing the spine.

- Diaphragmatic Bracing: Practice "360-degree breathing." Don't just breathe into your chest. Feel your lower ribs and even your lower back expand as you inhale. This creates internal pressure that supports the spine from the inside.

- Hinge, Don't Squat: Learn to move at the hips. When you pick up a laundry basket, your spine shouldn't change shape. Your hips should act like a hinge, while the lumbar muscles stay "quiet" and isometric.

- Walk more: Seriously. Walking is a natural "pumping" mechanism for the spinal discs. It alternates the load on the lumbar muscles, preventing them from seizing up in one position.

The goal isn't just to have "strong" muscles. It's to have "smart" muscles. Your back needs to know when to turn on and, more importantly, when to relax. Most chronic back sufferers have muscles that are stuck "on" at a low hum all day, which leads to fatigue and eventual injury. Relaxing the psoas while strengthening the glutes (the engine of the body) is often the secret sauce. When the glutes work, the lower back doesn't have to.

If you treat your back like a single unit rather than a collection of separate parts, it starts to behave. Focus on stability first, mobility at the hips and mid-back second, and never ignore the small muscles you can't see in the mirror. That's where the real support happens.