Honestly, if you think "cancel culture" is a new invention of the Twitter era, you've never met Katharina Blum. This isn't just some dusty German novel from 1974. It’s a terrifyingly accurate blueprint of how a person’s life can be dismantled in roughly four days by a toxic cocktail of tabloid lies and police ego.

The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum is basically a post-mortem of a character assassination. Heinrich Böll—who actually won a Nobel Prize—wasn't just writing a story; he was screaming at the German public. He was fed up with the Bild-Zeitung, a massive real-life tabloid that spent the 70s turning everyone into a suspected terrorist.

Why This Story Still Hurts Today

The setup is deceptively simple. Katharina is a housekeeper. She’s quiet, hardworking, and earned the nickname "the nun" because she’s so private. Then she goes to a party. She meets a guy named Ludwig. They spend one night together.

Boom. Her life is over.

It turns out Ludwig is a suspected bank robber and "terrorist" (the quotes are heavy here because the book leaves his actual guilt kinda murky). The police storm her apartment the next morning, but he’s already gone. Enter Werner Tötges, a reporter for "The News."

✨ Don't miss: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

Tötges is the villain you’ll love to hate. He doesn’t care about the truth; he cares about the "story." He interviews Katharina's dying mother in the hospital and twists her words so badly that the poor woman literally dies from the stress. He paints Katharina as a "communist whore" and a "terrorist bride."

The Violence Nobody Talks About

The subtitle of the book is How violence develops and where it can lead.

Most people hear "violence" and think of the ending—spoiler alert: Katharina shoots the journalist—but Böll is talking about the violence of the pen. The way a headline can be a physical blow. The way a photographer’s flash can feel like an assault.

What the History Books Skip

To understand why this was such a big deal, you have to look at the 1970s West German "German Autumn." The Baader-Meinhof Group (the RAF) was blowing things up. The government was panicking. They passed laws making it easy to wiretap people and search homes without much cause.

🔗 Read more: Greatest Rock and Roll Singers of All Time: Why the Legends Still Own the Mic

Böll himself was targeted. He wrote an article asking for Ulrike Meinhof to get a fair trial, and the tabloids branded him a "spiritual father of terrorism." They even searched his house. He wrote The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum as a "fictional" revenge because he was living through the exact same nightmare.

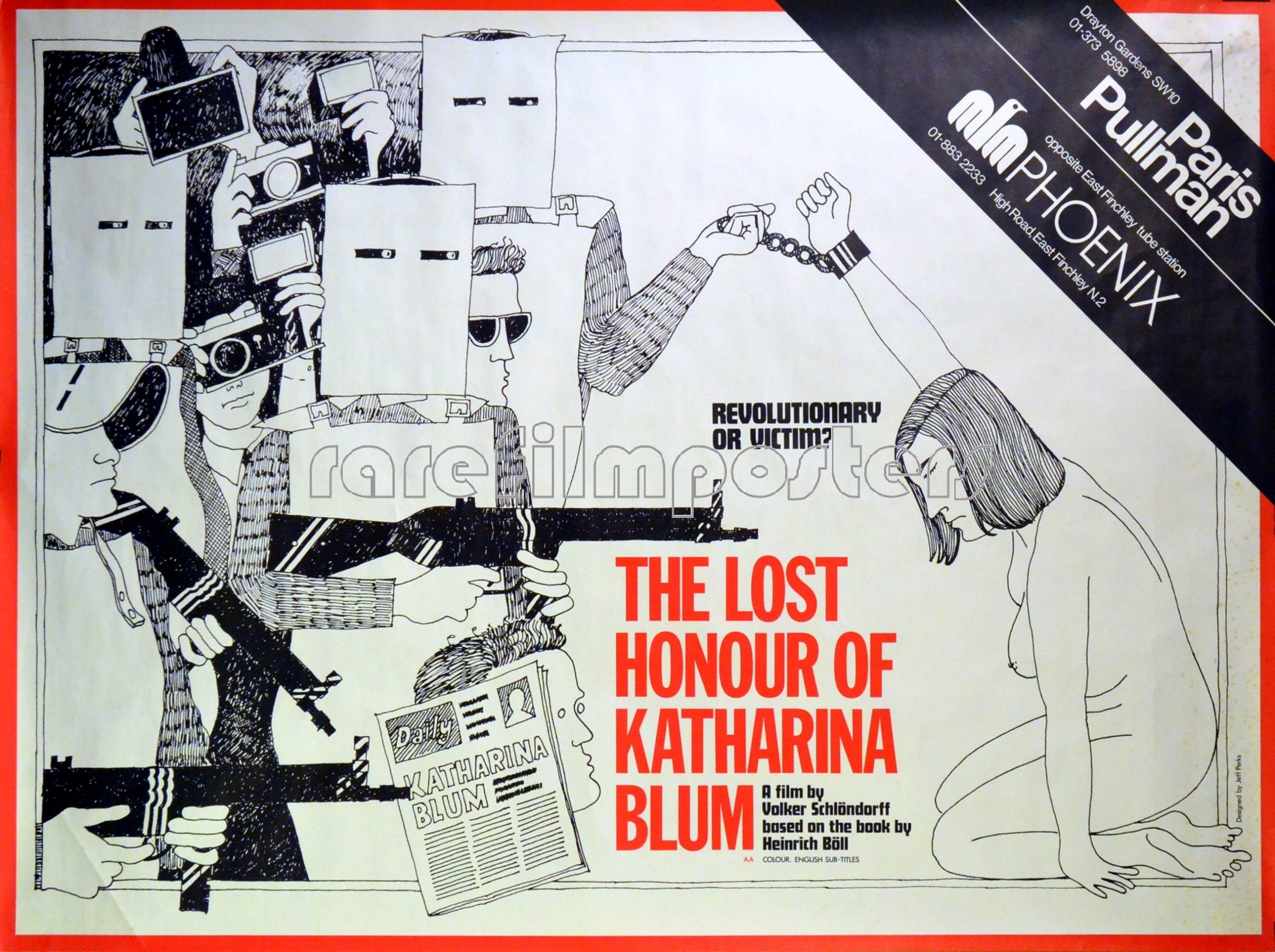

The Movie vs. The Book

In 1975, Volker Schlöndorff and Margarethe von Trotta turned it into a film. It’s stark. It’s grey. It’s brilliant.

One big difference? The film is way more overt about the sexism. In the book, the narrator is cold and documentary-like. In the movie, you see the leers. You see the police inspector, Beizmenne, asking Katharina if Ludwig "f***ed" her. It’s meant to make your skin crawl.

The film also ends at Tötges’ funeral, where his boss gives this incredibly hypocritical speech about "freedom of the press." It’s a gut-punch because it shows that even after the murderer is caught, the machine that created her doesn’t stop. It just finds a new victim.

💡 You might also like: Ted Nugent State of Shock: Why This 1979 Album Divides Fans Today

How to Apply These Lessons

If you're looking at the media today—whether it's a 24-hour news cycle or a viral TikTok takedown—the patterns in this book are everywhere.

- Look for the "Word-Twisting": Notice how Tötges takes "she is a very clever person" and turns it into "she is a cold, calculating mastermind."

- The Power of Privacy: Katharina’s "honour" isn't about her virginity. It’s about her right to be a private citizen. Once the media took that, she had nothing left to lose.

- Check the Source: Böll starts the book with a disclaimer saying that if the "journalistic practices" described resemble the Bild-Zeitung, it’s "neither intentional nor accidental, but unavoidable." That’s the ultimate 1970s "I said what I said."

Your Next Steps

If you want to really "get" this story, don't just read a summary.

- Watch the 1975 film: It's often on Criterion or MUBI. The performance by Angela Winkler is haunting.

- Compare a modern scandal: Take a look at a recent "public shaming" on social media. Count how many "Tötges-style" leaps of logic you see in the comments.

- Read Böll’s essays: If you want the raw, non-fiction version of his anger, look up his 1972 piece "Sixty Million against Six." It’s the spark that lit the fire for the novel.

Ultimately, the story reminds us that when we treat people like "content" instead of humans, we shouldn't be surprised when they eventually break.