If you’ve spent any time in the darker corners of the internet—the places where people argue about ancient aliens, gold mining in Africa, and a rogue planet called Nibiru—you’ve run into it. The Lost Book of Enki. It sounds like an archaeological bombshell. A dusty, forgotten manuscript dug out of a desert.

But it isn't. Not really.

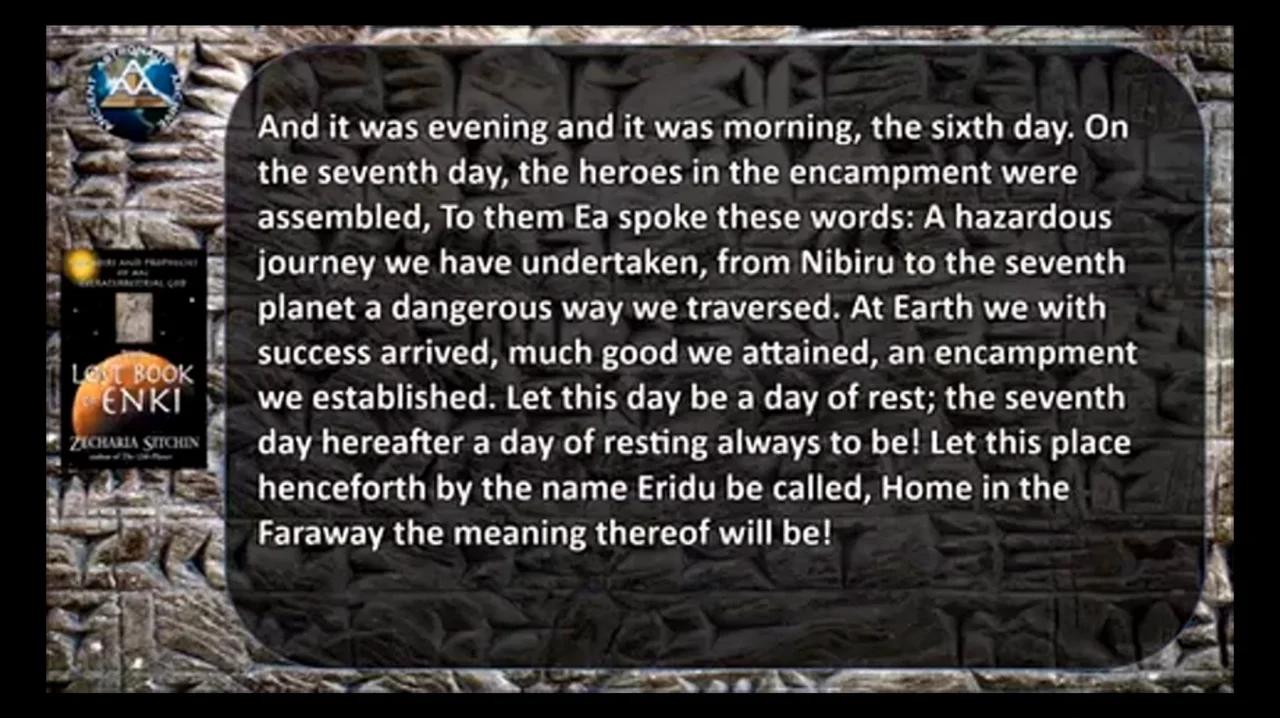

Let's get one thing straight immediately: this is not a translation of a 5,000-year-old clay tablet. It’s a book written by Zecharia Sitchin and published in 2001. Sitchin was a prolific writer, a researcher of ancient Hebrew and Sumerian texts, and a man who honestly believed he’d cracked the code of human history. He presented this specific work as a "memoir" written by the Sumerian god Enki. He used the "lost book" framing to reconstruct what he believed was the true narrative of the Anunnaki.

It’s basically the "Silmarillion" of the Ancient Astronaut theory.

People get mad about this. Scholars roll their eyes. Fans treat it like a bible. The reality is somewhere in the middle, sitting right at the intersection of myth, creative interpretation, and a very specific type of historical detective work that ignores most conventional rules of linguistics.

Why The Lost Book of Enki Still Matters Today

Why are we still talking about this decades later? Why is it popping up on TikTok and Reddit in 2026?

Because the story is incredible.

Sitchin weaves a tale that explains everything from the missing link in human evolution to the origin of the asteroid belt. According to the narrative, the Anunnaki—beings from the planet Nibiru—came to Earth about 450,000 years ago. They didn't come for a vacation. They came because their atmosphere was failing and they needed gold to suspend in their air to reflect heat.

Think about that for a second. It's basically a sci-fi geoengineering project gone wrong.

Enki, the protagonist, is portrayed as a brilliant scientist. He’s the one who supposedly decided to genetically engineer a "Primitive Worker" (us) to take over the back-breaking labor in the mines. If you read the book, Enki describes the trial and error of splicing Anunnaki DNA with that of early hominids. He talks about the failures—creatures that couldn't hold their bladder, or those with non-functioning organs—until they finally "perfected" the Adamu.

📖 Related: The Betta Fish in Vase with Plant Setup: Why Your Fish Is Probably Miserable

It’s gripping. It’s also wildly controversial.

The Sumerian Problem

Here’s where it gets tricky. If you talk to an actual Assyriologist—someone like the late Dr. Michael Heiser—they’ll tell you Sitchin’s translations are, well, imaginative.

For instance, the word Anunnaki. In standard Sumerian studies, it generally refers to "those of royal blood" or "princely offspring." Sitchin translated it as "those who from heaven to earth came." That’s a massive leap. It changes the context from local mythology to intergalactic travel.

Sitchin wasn't just translating; he was interpreting through a very specific lens. He looked at cylinder seals—small stone rollers used to print images on clay—and saw things others didn't. The famous VA 243 seal is a prime example. To Sitchin, it showed our solar system with twelve planets (including the sun and moon). To a conventional historian, it’s a depiction of a deity and some stars that don't match any astronomical map.

It's a clash of worldviews. You've got the academic world saying, "Show us the grammar," and you've got the Sitchin camp saying, "Look at the big picture."

The Great Flood and the Genetic Code

One of the most intense parts of The Lost Book of Enki involves the Deluge. Sitchin’s Enki claims the flood wasn't an act of God, but a natural disaster caused by Nibiru’s gravitational pull. Enlil, Enki’s brother and rival, wanted to let humanity drown. He saw us as a noisy nuisance.

Enki, the creator-father, couldn't do it.

He supposedly leaked the "secret" to Ziusudra (the Sumerian Noah), giving him the specs for a submersible craft. He even mentions "preserving the life seeds"—DNA. This reframes the entire biblical Ark story. It goes from a giant wooden boat full of giraffes to a high-tech preservation of genetic material.

Honestly, it makes for a much better movie.

👉 See also: Why the Siege of Vienna 1683 Still Echoes in European History Today

But we have to look at the sources. Sitchin drew from the Atrahasis, the Enuma Elish, and the Epic of Gilgamesh. He took these disparate, often fragmented stories and smoothed them into a single, chronological first-person account. It’s a masterful piece of literature, even if you don't believe a word of it as "history."

Gold, Monatomic Elements, and the Anunnaki Motivation

Let’s talk about the gold. Why gold?

Sitchin suggests the Anunnaki needed it for their home planet. In modern alternative circles, this has evolved into theories about "monatomic gold" or "white powder gold" that grants longevity. The book describes the Anunnaki as being "immortal" compared to humans, but only because their lifespans were tied to the orbit of Nibiru—one Shar, or 3,600 Earth years.

To them, we were like mayflies. We lived, died, and were forgotten in the blink of an eye.

This creates a weirdly nihilistic but fascinating view of human purpose. We weren't created for "glory" or "love." We were a labor-saving device. A biological shovel.

The Controversy of the 12th Planet

You can't discuss Enki without discussing Nibiru. Sitchin claimed there’s a massive planet on a 3,600-year elliptical orbit that swings into our inner solar system.

NASA hasn't found it.

Now, astronomers have found evidence of "Planet Nine"—a massive body way out beyond Pluto. But its orbit doesn't match Sitchin’s timeline. This is the biggest hurdle for people who want to take The Lost Book of Enki as literal truth. If the planet isn't there, the whole house of cards starts to wobble.

However, proponents argue that the "celestial battle" described in the book explains the current state of our solar system. Enki describes a collision between a moon of Nibiru and a planet called Tiamat. This collision supposedly split Tiamat in two: one half became Earth, and the other half was shattered into the asteroid belt (the "Hammered Bracelet").

✨ Don't miss: Why the Blue Jordan 13 Retro Still Dominates the Streets

It's a neat way to explain the "Big Whack" theory of the Moon's formation, but it lacks the mathematical backing of modern astrophysics.

How to Read Sitchin Without Losing Your Mind

If you’re going to pick up a copy, go into it with eyes wide open. Don't treat it like a peer-reviewed history book.

- Look at it as an Epic: Treat it like the Odyssey or the Iliad. It’s a foundational myth for the modern age.

- Compare the Sources: Read the actual Enuma Elish. See where Sitchin followed the text and where he added his own "connective tissue."

- Check the Language: Understand that Sumerian is an isolate language. It’s incredibly hard to translate. One sign can have five different meanings depending on the context. Sitchin often chose the most "technological" meaning possible.

There is a certain "kinda" brilliance in how he connected the dots. He looked at the "sons of God" in Genesis 6 and compared them to the "Watchers" in the Book of Enoch and the Anunnaki of Sumer. He saw a global pattern. Whether that pattern is real or a result of human pareidolia—seeing faces in the clouds—is the million-dollar question.

What Most People Miss: The Internal Conflict

The heart of the book isn't actually the aliens. It's the family drama.

The rivalry between Enki and Enlil is the core of the story. Enki represents the scientist, the rebel, the one who loves his creation. Enlil represents the administrator, the rule-follower, the one who views humans as a mistake.

This archetype shows up in every culture. Prometheus vs. Zeus. Cain vs. Abel. It’s the struggle between freedom and control. By framing it through the "Lost Book," Sitchin suggests that our very DNA is a battleground for these two opposing philosophies.

We are, in a sense, the children of a broken home.

Actionable Insights for the Curious Researcher

If you want to dive deeper into the world of the Anunnaki and the claims made in The Lost Book of Enki, don't just stop at Sitchin. You need a balanced diet of information.

- Read the "Digital Hammurabi" YouTube channel: They are actual experts who break down Sumerian grammar and show exactly where Sitchin's translations deviate from standard scholarship. It’s a reality check.

- Explore the "Planet Nine" hypothesis: Look into the work of Konstantin Batygin and Michael Brown at Caltech. They are finding real evidence of a massive distant planet, but for scientific reasons, not mythological ones.

- Study the "Out of Africa" theory vs. "Genetic Acceleration": Look at the actual fossil record. Does it support a sudden jump in intelligence 300,000 years ago? Some say yes, others say it was a slow burn.

- Visit the British Museum's online collection: Search for "Sumerian cylinder seals." Look at the images yourself. See if you can spot the "rockets" and "planets" Sitchin talked about.

The real "secret" isn't necessarily that aliens landed in the desert. The secret is that our history is much weirder and more complex than we were taught in third grade. Sitchin may have been wrong about the details, but he was right about one thing: we are a species with amnesia. We are desperately trying to remember where we came from.

The Lost Book of Enki is just one man's attempt to fill in the blanks. Whether it’s a map to the past or a work of creative fiction, it has fundamentally changed how millions of people look at the stars and our own origin story. It challenges the "status quo" of history, and in a world where we’re constantly discovering new hominid species like the Denisovans, maybe being a little skeptical of the "official" timeline isn't such a bad thing.