Loneliness is a weirdly shameful thing to admit to. We live in a world where everyone is technically "connected" through a glass screen in their pocket, yet the actual sensation of being alone—really, bone-deep alone—feels like a personal failure. That’s the exact nerve Olivia Laing touches in her 2016 book, The Lonely City. It’s not just a memoir. It's not just an art history book. It’s a survival guide for people who feel like they’re drifting through a crowded room.

Laing moved to New York City for love. Then the relationship imploded. Suddenly, she was in one of the most densely populated places on Earth, living in a series of sublets, and feeling completely invisible. Most people would have just downloaded more apps or moved back home. Instead, she started looking at art. She started wondering if loneliness was actually a place, and if so, who else lived there?

What people get wrong about The Lonely City

A lot of readers go into this expecting a "sad girl" manifesto. It’s way more than that. Laing looks at loneliness as a political and social construct, not just a feeling. She dives into the lives of artists like Edward Hopper, Andy Warhol, Henry Darger, and David Wojnarowicz. These aren't just names in a museum; she treats them like companions.

Take Edward Hopper. You’ve seen Nighthawks. You know the one—the diner at night with the yellow light and the people who aren't talking to each other. People always say it’s about "urban alienation." But Laing looks closer. She notices how the glass of the diner window acts as a barrier. You can see the people, but you can’t reach them. That’s the essence of The Lonely City. It’s about being "out in the cold" while looking at the warmth of others.

Honestly, the way she writes about Warhol is what sticks with me. We think of him as this social butterfly, the guy at the center of The Factory, always surrounded by drag queens and superstars. But Laing argues that his obsession with tape recorders and cameras was a way to mediate his terror of actual intimacy. He used technology to keep people at a distance. Sound familiar? It’s basically exactly what we do with our phones today. We use the screen to "see" people without the messiness of actually being seen ourselves.

🔗 Read more: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessing Over Maybelline SuperStay Skin Tint

The art of being alone in a crowd

The book shifts gears when it hits David Wojnarowicz. This is where it gets heavy. He was an artist and activist during the AIDS crisis in New York. His loneliness wasn't just about a breakup; it was about being part of a community that was being systematically ignored and erased by the government.

Loneliness is often a byproduct of exclusion.

If you’re queer, if you’re sick, if you’re poor, the city becomes a very different place. Laing doesn't shy away from the gritty stuff. She talks about the piers where men went for anonymous sex—not because they were "depraved," but because they were looking for a way to connect in a world that told them they didn't belong. It’s a radical way to look at the topic. She suggests that maybe our loneliness isn't a "glitch" in our personality. Maybe it’s a natural response to a world that builds walls.

Then there’s Henry Darger. He was a janitor in Chicago who worked in total obscurity. After he died, his landlords found this massive, thousands-of-pages-long epic called The Story of the Vivian Girls. He spent his whole life in a single room, creating an entire universe. Was he lonely? Probably. But his work shows that loneliness can also be a space for incredible, wild creativity. It’s not just a vacuum. It’s a landscape.

💡 You might also like: Coach Bag Animal Print: Why These Wild Patterns Actually Work as Neutrals

Why this book still matters (maybe more than ever)

We’re currently dealing with what experts call a "loneliness epidemic." It’s a buzzword now. But The Lonely City offers something a medical study can't. It offers empathy. It tells you that being lonely doesn't mean you’re broken. It means you’re human.

The prose is jagged and beautiful. Sometimes she spends five pages talking about the technicalities of a 1970s film, and then she’ll drop a sentence that makes you want to stare at a wall for twenty minutes. She writes about "the hyper-vigilance of the lonely." When you’re alone for a long time, you start to perceive social cues as threats. You get prickly. You push people away because you’re scared of being rejected. It’s a vicious cycle, and Laing maps it out with surgical precision.

The New York factor

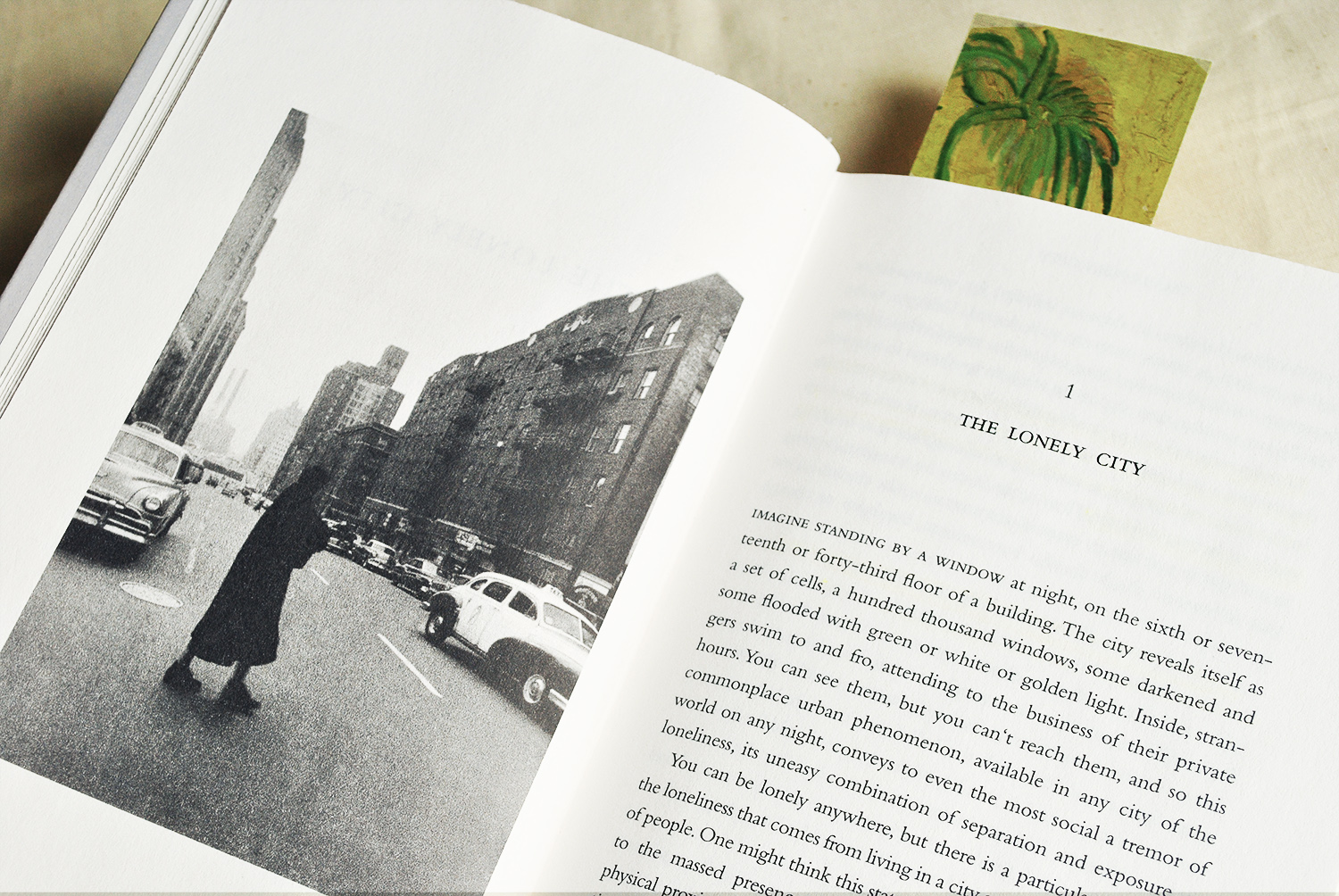

New York is the perfect setting for this. It’s a city of glass. You’re always looking into someone else’s apartment. You’re always seeing a life you aren't part of. Laing describes the experience of walking the streets at night, looking at the lighted windows, and feeling like a ghost.

But there’s a weird comfort in that.

📖 Related: Bed and Breakfast Wedding Venues: Why Smaller Might Actually Be Better

There’s a communal aspect to urban loneliness. You realize that the person in the apartment across the street is probably feeling the exact same thing. You’re alone, together. It’s a strange paradox that the book explores without ever getting too sentimental or cheesy.

Actionable insights: How to live in your own "lonely city"

Reading this book shouldn't just make you sad. It should change how you move through the world. If you’re feeling the weight of isolation, here are a few things to take away from Laing’s deep dive:

- Audit your "mediators." Like Warhol, are you using your phone to avoid people or to find them? If you’re scrolling to numb the pain of being alone, it’s probably making the "hyper-vigilance" worse. Try to look at people's faces in the street instead of your screen, even if it’s scary.

- Turn your loneliness into a "study." When Laing felt the most isolated, she went to the archives. She became a detective of other people's lives. If you’re stuck in a rut, find a topic, an artist, or a piece of history that resonates with your mood and go deep. Curiosity is the best antidote to the "shame" of being alone.

- Recognize the "Glass Barrier." Understand that social media is exactly like Hopper’s diner window. You’re seeing a curated, lit-up version of life. You aren't seeing the mess. Remind yourself that the "connectedness" you see online is an illusion of intimacy, not the real thing.

- Visit a museum or a public library. These are some of the few "third spaces" left where you can be around people without the pressure to perform or spend money. Just being in the presence of others while doing your own thing can lower your cortisol levels.

- Read the book. Seriously. If you’re feeling invisible, seeing your feelings reflected in Laing’s prose is a massive relief. It validates the experience.

Loneliness is a city. It has its own architecture, its own history, and its own residents. You might be living there right now, but you aren't the only one on the map. Olivia Laing proved that by walking the streets and looking at the art that came out of the shadows. The goal isn't necessarily to "cure" loneliness—it’s to learn how to inhabit it without being destroyed by it.

The next step is to stop treating your solitude like a secret. Once you realize that everyone else is just as terrified of being alone as you are, the walls of the city start to feel a little bit thinner. Go to a gallery. Sit in a park. Be lonely, but do it with your eyes open. It makes all the difference.