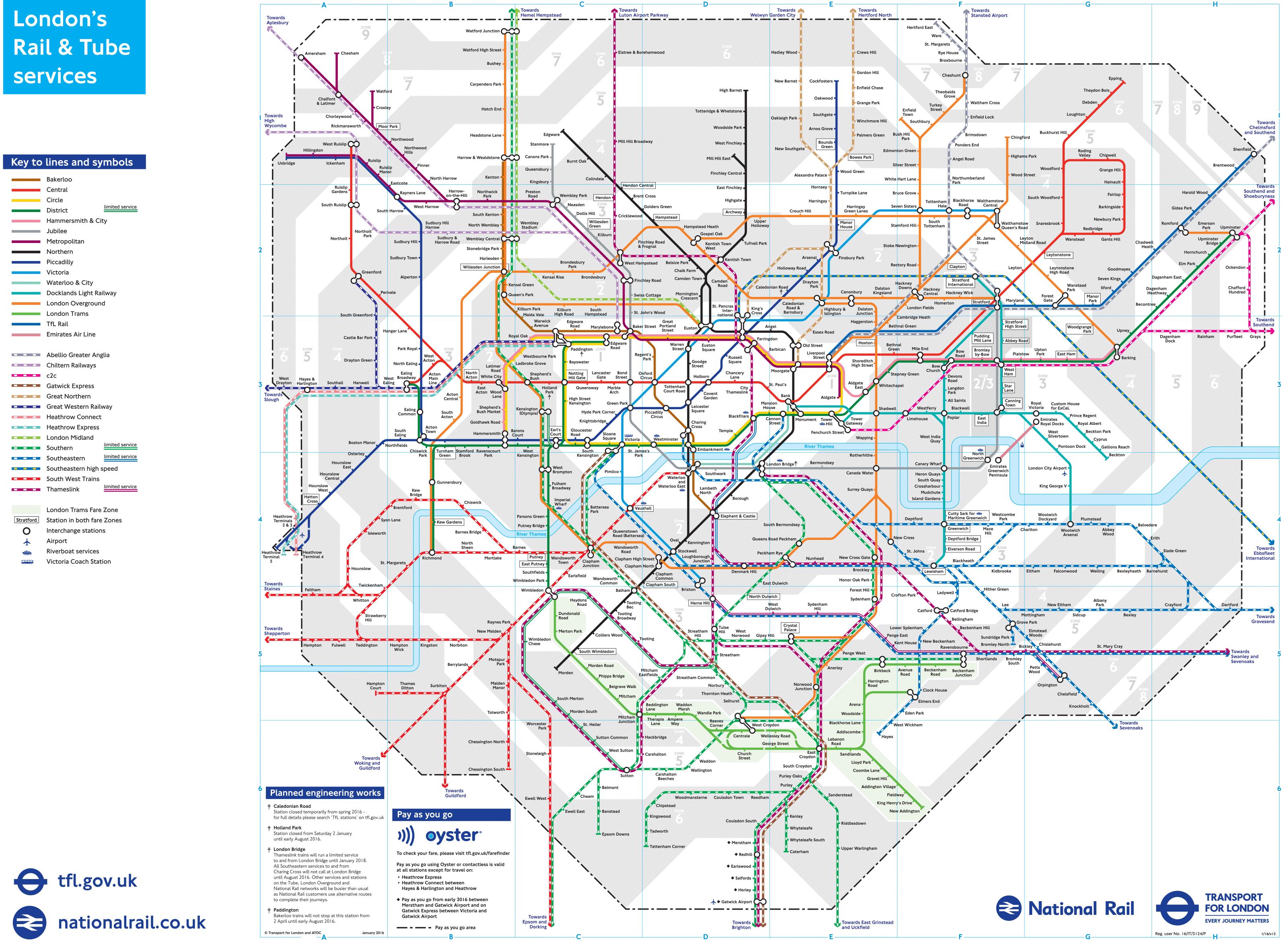

Getting lost in London is a rite of passage. You step off a plane at Heathrow, bleary-eyed and clutching a suitcase, only to be confronted by a multi-colored tangle of lines that looks more like a circuit board than a geographical representation of a city. That’s because it basically is a circuit board. The subway map London England uses today isn’t a map in the traditional sense. It’s a diagram. If you tried to walk the distance between Leicester Square and Covent Garden based on how they look on the map, you’d be done in about four minutes. But if you tried to do the same between two stops in Zone 6, you might find yourself trekking through a forest for an hour.

Maps are supposed to tell the truth. This one lies to you for your own good.

The history of the "Tube map" is actually a story of a massive gamble. Back in the late 1920s, the maps were literal. They showed the tracks exactly where they laid under the streets. The result? A messy, cramped cluster of stations in Central London and long, spindly lines stretching out into the suburbs that made the map look lopsided and incredibly hard to read. Enter Harry Beck. He wasn't some high-flying urban planner or a famous cartographer. He was a temporary draughtsman making a few pounds a week. He had this wild idea that people riding underground didn't care what was happening on the surface. They just wanted to know how to get from point A to point B.

The Logic Behind the Subway Map London England Relies On

Beck’s 1931 proposal was initially rejected. The authorities thought it was "too revolutionary." They didn't think the public could handle a map that ignored geography. But after a small trial run in 1932, the public went nuts for it. The design is based on three simple rules: lines are only vertical, horizontal, or at 45-degree angles. Stations are spaced somewhat evenly, regardless of their actual physical distance. This creates a sense of order in a city that is fundamentally chaotic.

Think about the Northern Line. It’s a nightmare of branches and "via Bank" or "via Charing Cross" deviations. On a real map, it looks like a nervous system having a breakdown. On the Tube map, it’s a clean, black vein that makes sense at a glance. It’s iconic. It’s also arguably the most successful piece of information design in human history. It has been copied by New York, Tokyo, Paris, and basically every other major transit system on the planet.

But there’s a catch to all this tidiness.

Because the subway map London England prints on every tourist brochure is a diagram, it creates a psychological "map" of the city that isn't real. This leads to the classic "tourist trap" of taking the Tube between stations that are actually closer on foot. For example, the journey from Charing Cross to Embankment. On the map, they are distinct stops. In reality? They are about 200 meters apart. You spend more time going down the escalator than you do on the train. People do this every day because they trust the diagram over their own feet.

👉 See also: 3000 Yen to USD: What Your Money Actually Buys in Japan Today

Navigating the Modern Expansion

The map has grown bloated lately. It’s not Beck’s fault, but the sheer volume of information being shoved into that frame is reaching a breaking point. We’ve added the Overground (the orange ginger-bread lines), the DLR (the turquoise dashed lines), the Thameslink (sort of), and now the Elizabeth Line. The Elizabeth Line—or "the Lizzy line" as locals call it—actually changed the game again. It’s technically not a "Tube" line; it’s a high-speed railway that happens to go underground.

When the Elizabeth Line was added to the map in 2022, designers had a minor crisis. Where does the purple go? How do you show that Paddington has two different station entrances that are half a mile apart? Honestly, the map is starting to look a little cluttered. There are now "wheelchair accessible" icons, "walking interchange" blobs, and river boat connections. It’s a lot. If you look at an original 1933 map compared to the 2026 version, the DNA is there, but it’s like looking at a wolf versus a pug.

Why the Map Scales Don't Match Reality

The distortion is most aggressive when you look at the suburbs. Take the Metropolitan Line. It snakes all the way out to Amersham and Chesham in Buckinghamshire. On the map, these look like they are just "a bit further" than Wembley. In reality, you are practically in another timezone.

- Zone 1: Tight, compressed, and geographically tiny.

- Zone 6-9: Massively stretched.

- The Thames: Curvy in real life, but rendered as a blocky, stylized ribbon on the map.

This distortion is necessary. If the map were "accurate," the center of London would be a tiny black dot of text that you’d need a magnifying glass to read, while the rest of the paper would be 90% empty space for the outskirts. By equalizing the station spacing, Beck allowed every commuter to feel like they were on the same grid. It democratized the city.

Interestingly, there have been many attempts to "fix" the map. Max Roberts, a psychology lecturer and map enthusiast, has spent years creating "curvy" versions of the map and geographically accurate versions. They are beautiful. They are also incredibly difficult to use for navigation. Your brain likes the 45-degree angles. It likes the grid. It’s why, despite the complaints about clutter, Transport for London (TfL) rarely messes with the core design language.

Symbols You Might Be Misinterpreting

Look closely at the station circles. You’ve got the standard "tick" for a station, and then you’ve got the "interchange" circles. A single white circle with a black border usually means you can change lines without leaving the station. But sometimes, you’ll see two circles connected by a thin black line. That’s a "walking out-of-station interchange." It means you have to tap out, walk down the street, and tap back in at a different entrance.

✨ Don't miss: The Eloise Room at The Plaza: What Most People Get Wrong

If you’re using a subway map London England provides at a station, look for the "dagger" symbol (†). It usually points to a footnote about a station being closed on weekends or having no lift access. Ignoring that little cross is the fastest way to end up stranded at a closed gate at 11:00 PM on a Sunday.

The Digital Shift and the Future of Paper

Is the paper map dead? Not really. Even though everyone has Google Maps or Citymapper on their phones, the "mental map" of London is still defined by the paper version. When someone says they live "on the Central Line," you immediately visualize that red horizontal stripe. The map is our collective shorthand for the city's geography.

However, the digital versions are getting smarter. TfL's official Go app now shows you exactly where the train is on the line. But even there, they use the Beck-style diagram. Why? Because geography is confusing. A line that curves around a park is harder for your brain to process than a straight line.

One thing most people don't realize is that the map is a copyrighted work of art. You can't just print it on a t-shirt and sell it without TfL's permission. They guard it fiercely. It’s not just a utility; it’s a brand. It’s the visual identity of London. The font used—Johnston Sans—is just as important as the colors. It was designed specifically for the Underground in 1916. It’s legible, humanist, and feels "London."

Practical Tips for Using the Map Today

If you want to move through London like a local, you have to learn to read between the lines. Literally.

First, ignore the map for short trips in the West End. If you are at Covent Garden and want to go to Leicester Square, just walk. Seriously. It’s about 250 meters. The map makes it look like a significant hop.

🔗 Read more: TSA PreCheck Look Up Number: What Most People Get Wrong

Second, check the "walking times" map. TfL actually publishes a version of the Tube map that shows how many minutes it takes to walk between stations. It’s a revelation. You’ll find that many "interchanges" are actually faster if you just walk above ground.

Third, pay attention to the Elizabeth Line's "double" stations. Farringdon and Barbican are linked by the Elizabeth Line platforms. You can enter at one and exit at the other. The map struggles to show this depth, but if you're savvy, you can save yourself a ten-minute walk in the rain by using the underground tunnels as a shortcut.

Fourth, understand the "Night Tube." Not every line runs 24 hours. The map usually has a specific "Night Tube" version where only the lines that run on Friday and Saturday nights are highlighted (usually the Victoria, Jubilee, and parts of the Central, Northern, and Piccadilly). If you’re looking at a standard map at 2:00 AM, you’re going to be disappointed when you find the Circle Line gates locked.

The subway map London England uses is a masterpiece of deception. It simplifies the world's most complex city into something a child can understand. It’s not perfect—it’s crowded, it’s geographically lying to you, and it’s constantly changing—but it’s the only way to make sense of the "Big Smoke."

Next time you’re standing on a platform, take a second to look at the map on the wall. Look at the way the lines intersect. It’s not just a way to find a train; it’s the skeleton of the city itself.

Actionable Insights for Navigating London:

- Download the "Walking Tube Map": Before you rely on the train, check the official TfL walking distance map. You’ll often find that "two stops away" is actually a 10-minute stroll.

- Trust the Purple: Use the Elizabeth Line for east-west travel. It’s faster, cleaner, and the stations are massive, even if the map makes it look like just another line.

- Mind the Gap (of Information): Always check the "Planned Works" posters at station entrances. The map won't tell you if a line is down for maintenance, but those white boards will.

- Look for the Wheelchair: If you have luggage or a stroller, only use stations marked with the blue wheelchair symbol. "Step-free" in London is a luxury, not a standard.