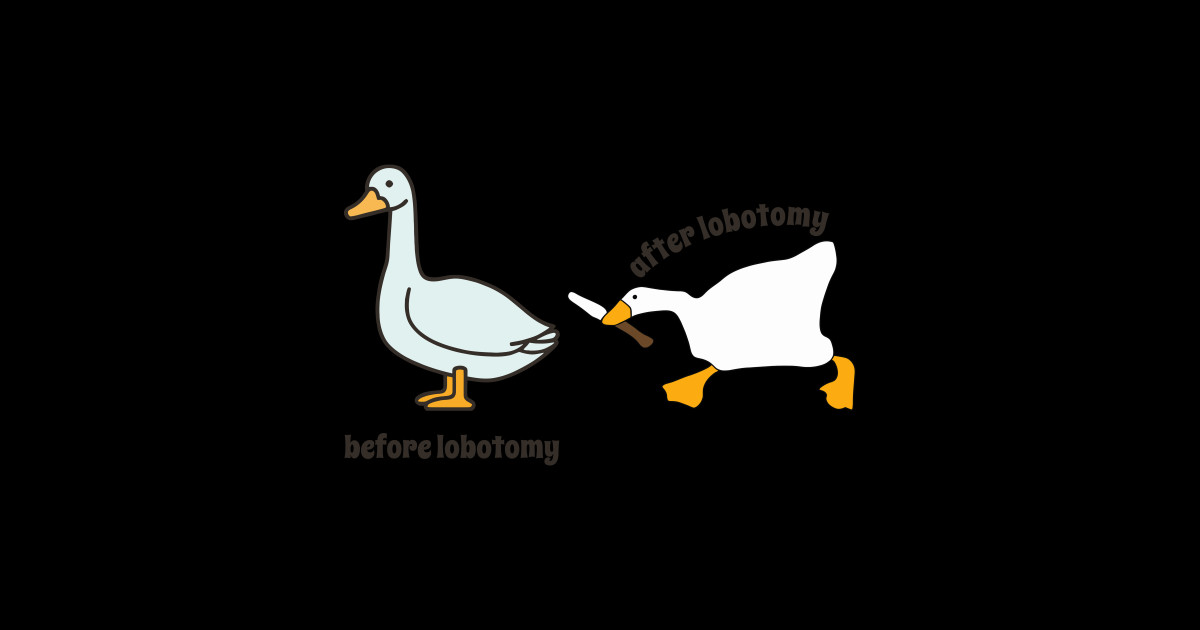

History is weird. Sometimes, the most tragic medical failures of the 20th century end up as a punchline on a TikTok feed or a "before and after" image macro. Lately, you might have seen people posting about the before and after lobotomy cigar trend. It’s a strange, dark corner of the internet where archival photos of patients are paired with captions about "vibes" or "moods." But if you look past the grainy black-and-white filters, the actual history of the transorbital lobotomy—and the people who lived through it—is way more intense than a meme suggests.

We’re talking about a procedure that was once the "gold standard" for difficult patients. It wasn't some back-alley surgery. It was mainstream.

Walter Freeman, the man who popularized the "ice pick" lobotomy, was a showman. He traveled the country in his "Lobotomobile." He’d walk into state hospitals, line up patients, and perform the surgery in minutes. No sterile operating room. No long recovery. Just a quick tap through the eye socket to sever the frontal lobes. The goal was to "fix" people. Usually, it just broke them.

The Before and After Lobotomy Cigar Imagery: Fact vs. Internet Fiction

When you search for before and after lobotomy cigar content, you're usually seeing a mix of genuine medical photography and unrelated vintage aesthetics. In the 1940s and 50s, doctors were obsessed with documenting "success." They’d take a "before" photo of a patient looking disheveled, angry, or anxious. Then, they’d take an "after" photo. In these, the patient is often sitting quietly. Maybe they’re smiling blankly. Sometimes, they’re holding a cigar or a pipe.

The cigar was a prop. It was used to signal "normalcy."

If a man who was previously catatonic or violent could now sit in a chair and enjoy a smoke, the medical community labeled it a win. But "normal" was a thin veneer. Underneath that calm exterior, most patients suffered from a permanent loss of personality, a "flattening" of the soul that left them child-like and easy to manage. They weren't cured; they were just quiet.

✨ Don't miss: How to get over a sore throat fast: What actually works when your neck feels like glass

Howard Dully: The 12-Year-Old Who Survived the Ice Pick

If you want a real story, look at Howard Dully. He’s one of the most famous living survivors of Walter Freeman’s work. Howard wasn't mentally ill. He wasn't violent. He was a 12-year-old kid who didn't get along with his stepmother. She described him as "defiant." She wanted him changed.

Freeman obliged.

In 1960, Howard was lobotomized. He spent decades wondering why he felt "empty" or why he couldn't quite connect with the world the way others did. He eventually found his medical records and realized what had been done to him. Howard’s "after" wasn't a success story about a cigar; it was a long, painful journey of a man trying to reclaim a brain that had been physically altered before he was even a teenager.

It’s honestly haunting. Freeman’s notes on Howard basically said the surgery was a success because he became "easier to handle." That was the metric. Convenience for the caregivers, not the quality of life for the patient.

Rosemary Kennedy and the High Cost of "Shame"

The Kennedy family is the ultimate example of the lobotomy’s dark peak. Rosemary Kennedy was vibrant but struggled with what we’d now likely call learning disabilities or perhaps a mood disorder. Her father, Joseph Kennedy, feared her "outbursts" would embarrass the family's political ambitions.

🔗 Read more: How Much Should a 5 7 Man Weigh? The Honest Truth About BMI and Body Composition

He scheduled a lobotomy in 1941.

Rosemary was 23. The surgery went horribly wrong. She was left with the mental capacity of a toddler, unable to speak or care for herself. She was hidden away in an institution for most of her life. This wasn't a "before and after" you’d see in a medical journal at the time. It was a family secret buried under layers of wealth and power. It shows that no amount of money could protect you from the "cutting edge" pseudoscience of the era.

Why the "Cigar" Photo Matters in Medical History

The use of cigarettes and cigars in medical photography from this era wasn't accidental. It was a social signifier. In the mid-20th century, smoking was a sign of adulthood, composure, and social integration. By posing a post-op patient with a cigar, Freeman and his peers were subconsciously telling the public: Look, they are one of us again.

But the reality was different.

- Patients often lost their "spark."

- They became incontinent.

- Their ability to plan for the future vanished.

- They became "zombies" in the eyes of their own families.

The before and after lobotomy cigar photos are essentially the 1950s version of a "staged" Instagram post. They show a curated version of reality designed to sell a product—in this case, a brutal surgical procedure.

💡 You might also like: How do you play with your boobs? A Guide to Self-Touch and Sensitivity

The Modern View: From Ice Picks to Neuroethics

We don't do lobotomies anymore. Not like that. The introduction of Thorazine in the 1950s—the first "chemical lobotomy"—basically killed the surgical practice. It was cheaper and didn't involve an ice pick. Today, we have deep brain stimulation and targeted surgeries for severe epilepsy, but the ethics are lightyears away from Walter Freeman’s era.

We now prioritize "informed consent." That’s something Howard Dully or Rosemary Kennedy never got.

When you see these memes today, it’s worth remembering that the people in those photos were human beings caught in a wave of medical hubris. They were victims of a "quick fix" mentality.

Actionable Takeaways for History and Health Buffs

If you’re interested in the real history behind the before and after lobotomy cigar trend, there are better ways to learn than through memes.

First, read My Lobotomy by Howard Dully. It is the single most important primary source for understanding what it felt like to be on the receiving end of Freeman’s tool. It’s raw, it’s sad, and it’s deeply eye-opening.

Second, check out the documentary The Lobotomist. It uses archival footage of Walter Freeman himself. Watching him perform the surgery is a visceral experience that strips away any "cool" vintage aesthetic the internet might try to put on it.

Finally, if you’re looking into the history of psychiatry, look for sources that focus on "patient agency." The history of medicine is usually written by the doctors. The real story is always with the people in the chairs, whether they’re holding a cigar or not. Stick to archives like the Wellcome Collection or the National Library of Medicine for the real photos—not the edited ones floating around social media. Understanding the context prevents us from repeating the same mistakes under new names.