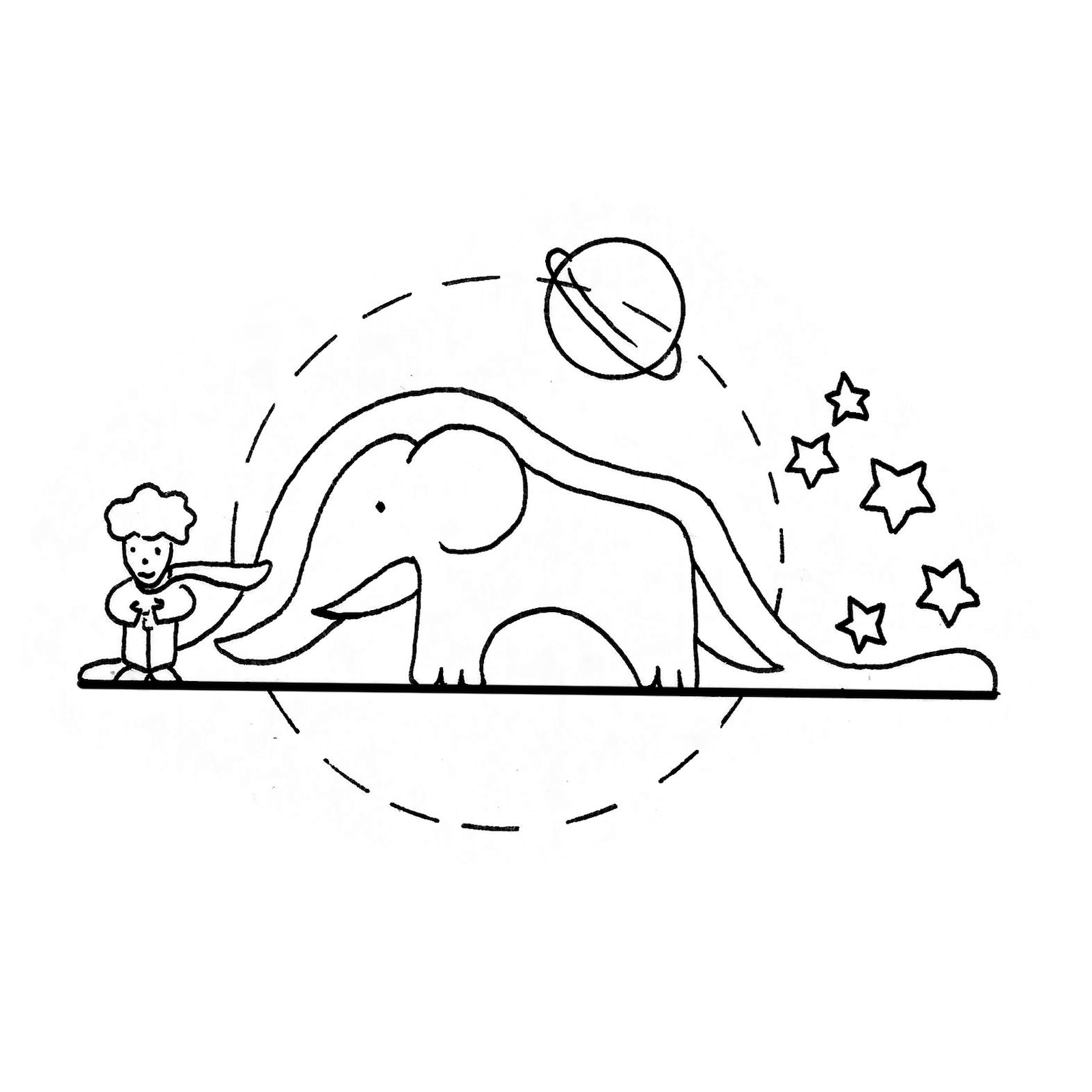

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wasn't just a pilot who happened to write; he was a man obsessed with the failure of adult perception. You’ve seen it. Everyone has. It’s that lumpy, brown shape that looks remarkably like a fedora or maybe a crumpled trilby. But if you’ve actually read the book—and I mean really sat with it—you know the little prince drawing isn't about headwear at all. It’s a litmus test for your soul.

Honestly, the opening of Le Petit Prince is kind of a gut punch to anyone who grew up and forgot how to use their imagination. The narrator draws a boa constrictor digesting an elephant. He shows it to the "grown-ups" and they ask him why they should be scared of a hat. It’s a simple gag, but it sets the stage for everything that follows. The grown-ups didn't see the elephant because they weren't looking for one. They were looking for something practical. Something you wear on your head to stay warm or look professional.

The Secret Geometry of the Little Prince Drawing

The brilliance of the little prince drawing lies in its intentional crudeness. Saint-Exupéry wasn't trying to be Picasso, though he was living in New York and Montreal during the early 1940s while writing it, surrounded by the high-art chatter of the era. He wanted something "naïve." That’s a specific art term, by the way. Naïve art is characterized by a childlike simplicity that bypasses formal training to get at a raw, emotional truth.

When the narrator finally draws the "inside" of the boa constrictor so the adults can understand, it’s almost an insult. He has to add the elephant's eye, the curve of its trunk, and the massive bulk of its body inside the snake's belly. It’s as if he’s saying, "Since you’re too blind to see the obvious, I’ll map it out for you like a blueprint." This second version of the little prince drawing is the one that really matters because it represents the death of mystery. Once you explain a joke, or a drawing, it loses its power.

Why the Sheep in the Box is the Real Masterpiece

Later in the Sahara, when the Prince asks for a sheep, we see the narrator fail three times. The first sheep is too sickly. The second is actually a ram (it has horns). The third is too old.

Exhausted and in a rush to fix his plane's engine, the narrator scribbles a wooden box with three holes. "The sheep you asked for is inside," he says.

💡 You might also like: Why A Decade of Hits Charlie Daniels Album Is Still the Blueprint for Southern Rock

This is the most important little prince drawing in the entire 140-page manifesto. Why? Because it requires the viewer to do the work. The Prince leans in, sees the sheep sleeping, and is perfectly happy. This isn't just a cute story beat. It’s a profound statement on the limitations of visual art. No matter how well you draw a sheep, it won't be the right sheep for everyone. But a box? A box can hold the infinite. It’s the ultimate interactive medium.

You’ve got to wonder if Saint-Exupéry was poking fun at the art critics of his time. He was a guy who spent his life in the cockpit of a P-38 Lightning, looking down at the world from 30,000 feet. From up there, things look different. Details blur. The "truth" of a landscape is its shape and light, not the individual trees.

The Technical Reality of the 1943 Illustrations

Let’s get into the weeds for a second. The original watercolors were done on "onionskin" paper. If you’ve never felt it, it’s that incredibly thin, almost translucent paper people used for airmail. It’s fragile. It bleeds.

Because the paper was so thin, Saint-Exupéry’s colors have this ethereal, washed-out quality that feels like a dream or a fading memory. This wasn't just an aesthetic choice; it was a matter of what he had available while living in exile. When Reynal & Hitchcock first published the book in 1943, they had to figure out how to reproduce these delicate washes. Most modern copies of the little prince drawing are actually quite far removed from the original vibrancy of those first watercolors.

In 2014, the Morgan Library & Museum in New York held an exhibition called "The Little Prince: A New York Story." They showed the original manuscripts. If you saw them, you’d notice something weird: there are coffee stains. There are cigarette burns. The little prince drawing wasn't born in a pristine studio; it was born in apartments on Central Park South and Bevin House on Long Island, amid the stress of a world at war and a pilot's desperate need to return to the sky.

Misconceptions About the Prince’s Appearance

People think the Prince always looked the way he does on the cover—the green suit, the red scarf, the sword. But if you look at the early sketches, Saint-Exupéry was playing with much stranger imagery.

- In some versions, the Prince looks more like a classic "cherub."

- In others, he’s almost featureless, just a silhouette against the stars.

- The scarf was a late addition, likely inspired by the scarves pilots wore to keep their necks from chafing while scanning the horizon for enemy planes.

The little prince drawing of the Prince standing on his tiny asteroid (B-612) is the one that stuck. It captures that feeling of isolation we all felt as kids—the idea that you are the sole ruler of a very small, very fragile world that you have to rake out (the volcanoes) and weed (the baobabs) every single day.

The Baobabs: A Warning in Ink

We can’t talk about the drawings without talking about the Baobabs. Those terrifying, planet-crushing trees.

📖 Related: Why I Wanna Feel the Heat With Somebody Still Hits Different Decades Later

Saint-Exupéry was writing in 1942 and 1943. He was a Frenchman watching his country occupied by Nazis. When he draws the three massive trees literally tearing a tiny planet apart with their roots, he isn't just talking about gardening. He’s talking about the "weeds" of fascism and hate. He explicitly tells the reader that they must "check the baobabs" every morning.

The little prince drawing of the baobabs is arguably the most detailed in the book. It’s dense, dark, and claustrophobic. It’s the only time the art feels threatening. It serves as a reminder that the book isn't just a whimsical fairy tale; it’s a survival manual for the human spirit.

How to Look at the Little Prince Drawing Today

If you’re looking at these illustrations today, don't look at them as "art." That’s a grown-up mistake. Look at them as messages.

When you see the Fox, don’t judge the proportions. Look at the ears. They’re massive. They’re alert. The Fox is the one who teaches the Prince about "taming" and responsibility, and the drawing reflects that—he is all ears, ready to listen, ready to be connected.

The sunset drawing—the one where the Prince watches the sun go down forty-four times because his planet is so small—is basically just a few lines and a wash of yellow. It’s minimalist. But it communicates a sadness that a high-definition photograph could never touch. It’s about the economy of emotion.

Actionable Ways to Engage with the Art

If you want to truly understand the little prince drawing, you have to stop being a spectator.

- Draw your own box. This sounds like a kindergarten exercise, but try it. Draw a box and decide what’s inside. Don’t tell anyone. See if the "not knowing" makes the object inside feel more real to you.

- Compare editions. Go to a used bookstore. Find an old, beat-up copy from the 60s and compare it to a modern "luxury" edition. You’ll notice the colors change. The line weights change. The "feel" of the art changes depending on the paper quality.

- Read the manuscript notes. Look up the digitized versions of Saint-Exupéry’s original drafts. You’ll see that he often drew in the margins of his letters. The little prince drawing was a habit, a way of thinking, long before it was a book.

- Practice "Active Perception." Next time you see a cloud or a stain on the sidewalk, don't just identify it. Ask yourself what else it could be. Force your brain to see the elephant inside the boa constrictor.

The little prince drawing is a challenge. It’s asking you if you’re still capable of seeing the world with enough wonder to find a sheep in a box or a forest in a single leaf. If you can’t see the elephant, don’t worry. It just means you’ve become a grown-up. But the good news is, you can always go back. The drawing is still there, waiting for you to see it correctly.

Focus on the "invisible" parts of the art. Like the Fox says, "Anything essential is invisible to the eyes." The ink and the paper are just the vehicle; the real drawing happens in your head. That’s why it’s survived for over eighty years. It’s not a fixed image; it’s a mirror. Whatever you see in that "hat" says more about you than it does about the snake. Check your baobabs, watch your sunsets, and for heaven's sake, keep an eye on that sheep. It might eat your rose if you aren't careful.