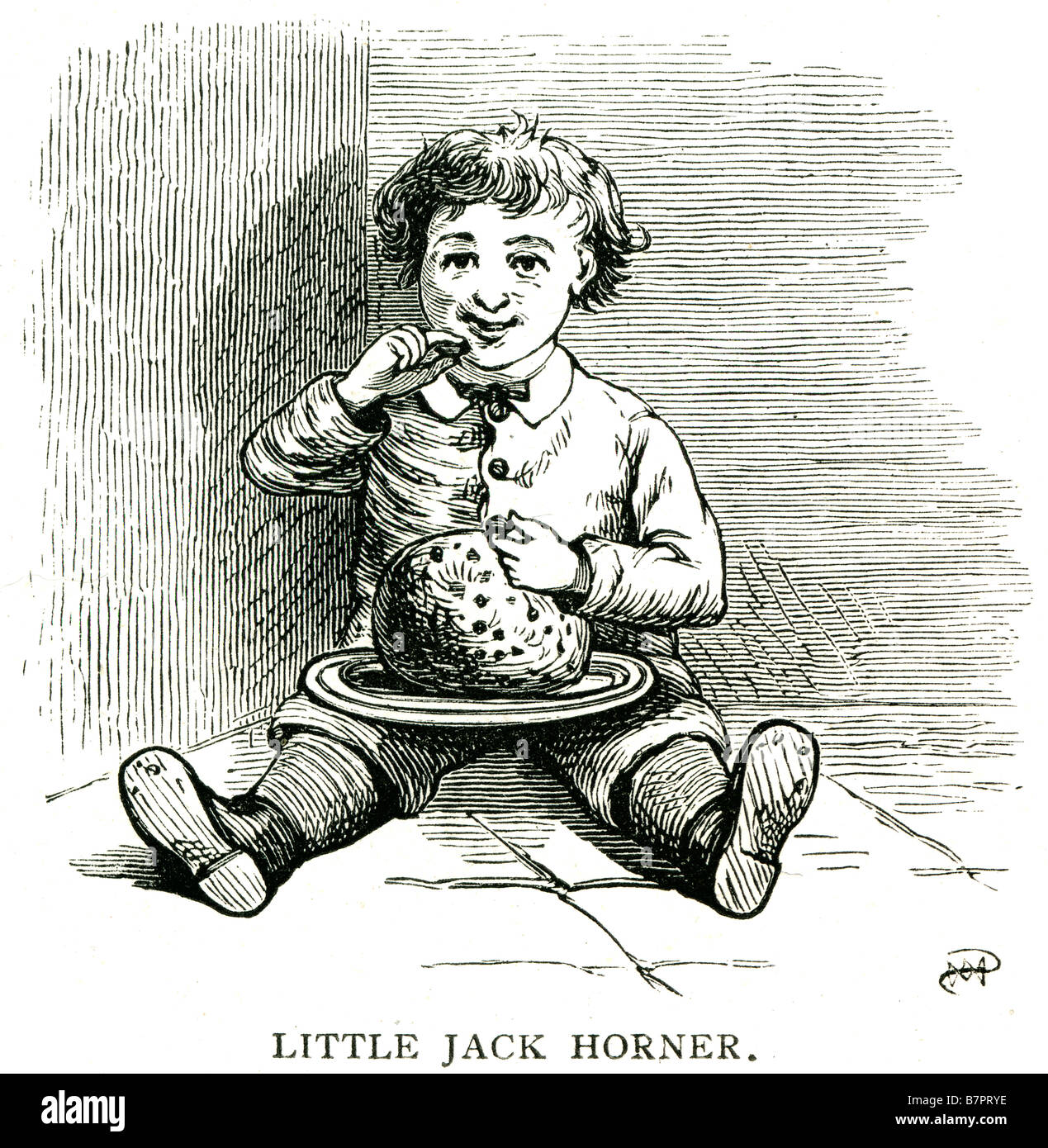

You probably remember the visual. A small boy, tucked away in a corner, aggressively sticking his thumb into a pie and pulling out a plum like he just won the lottery. It’s one of those nursery staples we recite to toddlers without thinking twice. But honestly, the little jack horner rhyme is kind of weird when you actually look at the words. Why is he in a corner? Why is he bragging about being a "good boy" for essentially playing with his food?

Most people assume it’s just nonsense. A catchy ditty to keep kids occupied.

The truth is way messier. It involves the dissolution of monasteries, a very stressed-out King Henry VIII, and a massive real estate "theft" that changed the map of Somerset forever. If you thought this was just about a kid with a sweet tooth, you’ve been misled by centuries of sanitized children's books.

The Story Behind the Little Jack Horner Rhyme

So, here’s the deal. Most historians point toward a real guy named Thomas Horner. This wasn't some tiny child; he was a grown man working as a steward for Richard Whiting, who happened to be the last Abbot of Glastonbury. This was back in the 1530s, a time when being a high-ranking Catholic official was basically like having a target painted on your back thanks to Henry VIII’s "Great Matter."

The King was hungry for land and gold. Glastonbury Abbey was rich. Really rich.

According to the local lore in Somerset—which the Horner descendants have spent centuries trying to debunk, by the way—Abbot Whiting tried to bribe the King to stay away. He supposedly sent Thomas Horner to London with a giant Christmas pie. But this wasn't filled with fruit. It was stuffed with the title deeds to twelve different manors. The "plum" Horner pulled out? That was allegedly the deed to Mells Manor.

He didn't find a piece of fruit; he found a massive estate.

💡 You might also like: Easy recipes dinner for two: Why you are probably overcomplicating date night

Why the "Good Boy" Line is Total Sarcasm

"What a good boy am I!"

In the context of the little jack horner rhyme, that line feels like a heavy dose of 16th-century shade. If the legend is true, Horner wasn't being good. He was being opportunistic. By "finding" the deed in the pie (or intercepting it on the way to the King), he essentially secured his family’s fortune for the next several hundred years.

It’s the ultimate inside joke.

Imagine a guy stealing a literal house and then walking around telling everyone how virtuous he is. That’s the energy of this poem. It’s political satire disguised as a lullaby. We do this a lot with history. We take these brutal, cynical political takedowns and turn them into something we recite while rocking a baby to sleep.

Does the Timeline Actually Fit?

History is rarely as clean as a rhyme.

Critics of the "Glastonbury Bribe" theory, including several geneologists, argue that the Horner family actually purchased Mells Manor fair and square after the Abbey was dissolved. They point out that the name "Jack" was often used as a generic term for a commoner or a "lad," much like how we use "Jack of all trades" today.

📖 Related: How is gum made? The sticky truth about what you are actually chewing

But there’s a catch.

The first time the little jack horner rhyme shows up in print is around the 18th century, though it was clearly part of oral tradition long before that. In 1725, Henry Carey mentioned it in a satirical poem. The fact that the rhyme persisted for hundreds of years suggests it was referencing something people actually cared about—namely, the massive redistribution of wealth during the Tudor era.

The Pie as a Medieval Safe

You might be wondering: who puts paperwork in a pie?

Back then, "surprise pies" were a legitimate thing. We aren't just talking about the "four and twenty blackbirds" situation. Savory pies with thick, inedible crusts—called coffyns—were used as vessels for all sorts of things. They were the Tupperware of the Middle Ages, but sturdier. Using a pie to smuggle sensitive documents past highwaymen actually makes a weird kind of sense. Nobody robs a guy for a pastry, right?

Unless they know there’s a manor house inside.

Breaking Down the Verse

Let's look at the structure. It’s simple, but effective.

👉 See also: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

- Little Jack Horner: Jack was a common nickname for Thomas.

- Sat in a corner: Some suggest this refers to the "corner" of the pie, or perhaps a secluded spot where he could secretly pilfer the deeds.

- Eating a Christmas pie: This pins the event to the winter of 1538-1539, right when the Abbey was under the most pressure.

- He put in his thumb: A vulgar gesture of greed or a literal reach for the prize.

- Pulled out a plum: "Plum" was slang for something desirable or a lucky find. In the 17th century, a "plum" also referred to the sum of £100,000—a massive fortune.

The Tragic End of the Real Abbot

While the rhyme stays lighthearted, the actual history is grim. Abbot Richard Whiting, Horner's boss, didn't fare so well. He was eventually accused of treason because he wouldn't hand over the Abbey. They dragged him to the top of Glastonbury Tor and executed him.

The Abbey was stripped of its lead, its stones, and its wealth.

If Thomas Horner did indeed walk away with Mells Manor while his boss was being executed, the "good boy" line becomes even darker. It’s a testament to how the survivors write the history—or in this case, how the disgruntled public writes the folk songs.

How to Explore This History Yourself

If you’re ever in the South West of England, you can actually see the "plum" for yourself. Mells Manor still stands in the village of Mells. It’s a stunning piece of architecture that remained in the Horner family for generations.

Walking through the village feels like stepping into the little jack horner rhyme.

The local church contains memorials to the Horners. You can see the landscape that was once at the heart of this Tudor land grab. It’s one of the few places where a nursery rhyme feels tangibly real.

Actionable Takeaways for History Buffs

- Research the Dissolution of the Monasteries: To understand the rhyme, you have to understand the massive power shift under Henry VIII. Check out Eamon Duffy’s The Stripping of the Altars for the full, heavy context of what was lost.

- Visit Glastonbury: Don’t just go for the festival. Go to the Abbey ruins. Stand at the spot where the pie would have been baked and look up at the Tor where the Abbot met his end.

- Check the Parish Records: Many UK archives are now digitized. You can find records of land transfers from the 1500s that show exactly how these "plums" were distributed among the local gentry.

- Read the Satire: Look up Namby Pamby by Henry Carey. It’s the first place the rhyme appears in a literary context, and it shows how 18th-century writers used these rhymes to mock their contemporaries.

The little jack horner rhyme isn't just a kids' song. It’s a survivor’s story. It’s a piece of political propaganda that outlived the government that inspired it. Next time you see a pie, just remember: there might be a deed to a mansion hidden under that crust, provided you’re "good" enough to find it.

To get the most out of this historical rabbit hole, start by looking at a map of the Somerset "Manors" mentioned in the 1530s records. Cross-reference them with the Horner family holdings. The overlap is more than just a coincidence; it's a map of a 500-year-old heist.